Measure J/Measure R campaigns seem to have devolved into an exercise where the opponents of a project attack the weaknesses of the project and the proponents of the project are forced to play defense – almost from the start. This week alone we have seen attacks on Nishi based on it being of insufficient size, on air quality concerns, on fiscal issues, and on the integrity of both the process of considering the proposal and the proposal itself.

If I have a criticism of Measure R – which I continue to support – it is first and foremost a politicization of the planning process which means that (A) positive aspects of the project are overlooked and negative aspects are emphasized, and (B) the need to put forward a project that can pass means that best practices may be ignored in favor of the art of the possible.

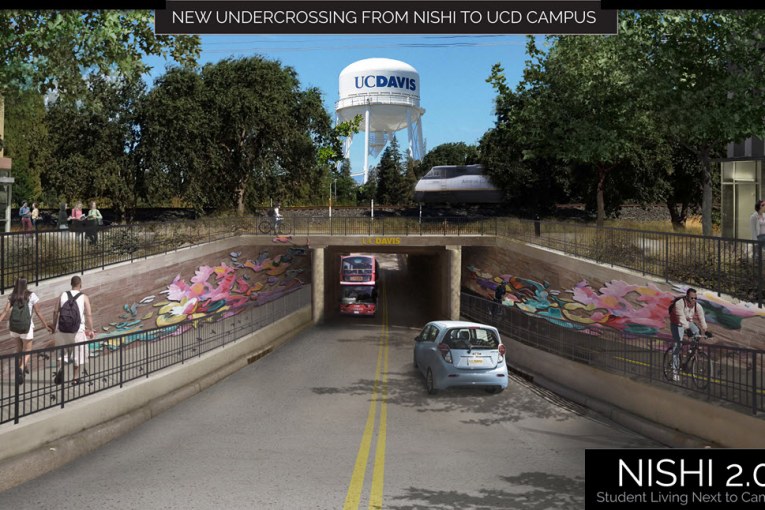

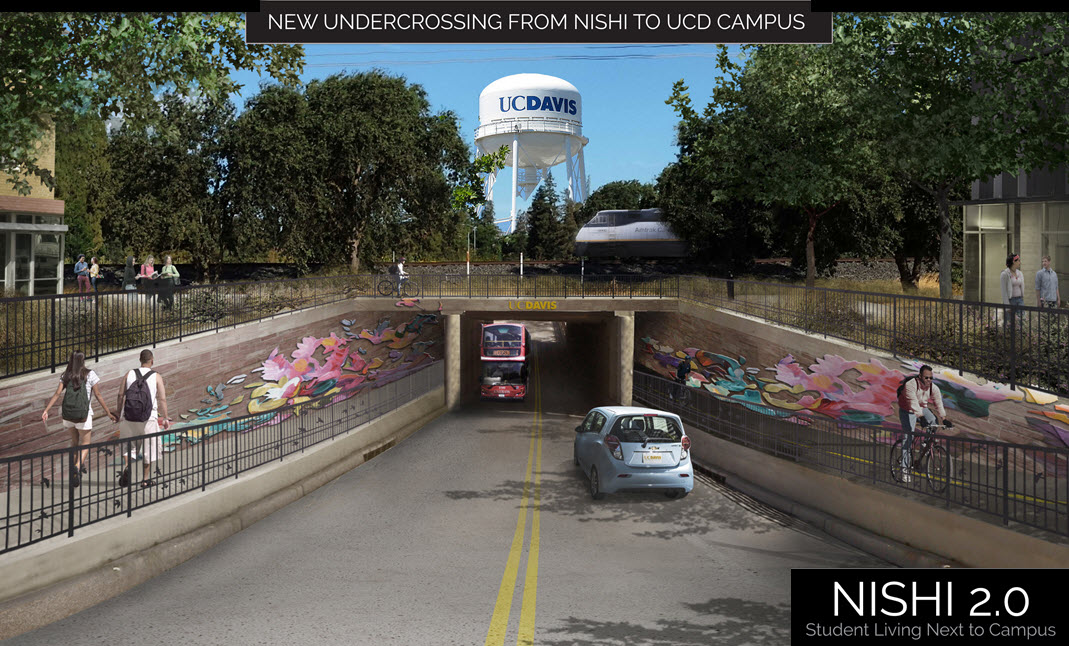

Nishi has always been seen as one of the top sites in the community. The positive is that it is next to campus within walking distance of the downtown. However, even though two versions were rated in the top 30 by the 2008 Housing Element Steering Committee, there has always been the challenge of access. The HESC actually ranked two versions of the project – the one with access to UC Davis only was rated more highly than the one with Olive Drive access.

One of the things I have learned about Davis is, while many claim to be environmentally focused, for the most part environmentally innovative projects are only advantaged in one way – it tends to remove an issue from the opposition. So if a project is not certified LEED-Gold for example, the project can and will be criticized. However, the project obtaining LEED-Gold status will not gain favor.

Sustainability is considered more a check box than a reason to vote for a project. So the fact that Nishi is a net zero energy project is not a reason why people will vote for it – it is simply a way to remove one possible argument against the project.

way to remove one possible argument against the project.

When the HESC evaluated Nishi in 2008, no one really realized that the driving issue would be student housing. At that time it was anticipated that Nishi would have 250 units – 125 multifamily ownership and 125 multifamily rental. The project currently sits at 700 – all rental, with 2200 projected beds for college students.

Here are what I see as reasons for people to vote for Nishi – it is of course up to them whether or not to ultimately support the project.

Housing Crisis

First and really foremost is we have a student housing crisis. Yesterday I ran through the math of UC Davis. From the city’s perspective, building Nishi means we add somewhere between 4000 and 5000 beds in the city. That means combined with the 5200 beds that UC Davis is supposed to add by 2020, we have a chance to add nearly 10,000 beds in the next three to five years – greatly alleviating the housing crisis.

The university ultimately projects to add 9050, but it is unclear when and where the rest of the 3800 beds would be built and, at the very least, the city would hedge its bets if the university does not follow through.

Those who believe that the university is primarily responsible for adding housing – this doesn’t let UCD off the hook. I think the most interesting thing is that, as the city has approved projects, it seems that these approvals have put more and not less pressure on the university to reciprocate. Observe that UC Davis came in with 6200 beds proposed in its LRDP. The city pushed for 50 percent on campus (10,000 additional beds) – the city then approved Sterling, Lincoln40 and put Nishi on the ballot, and yet the university has increased their commitment first to 8500 and then to 9050.

The critics were wrong that the city building housing would reduce the pressure on UC Davis. If anything, it gave the city the moral authority to say that we have stepped up – now it is your turn.

Traffic

The initial project lost in part because of traffic concerns on Richards Boulevard. Now, I happen to believe that the plan that the city and developers had in 2016 would have fixed Olive Drive by creating a bypass for people to get to campus without going through the tunnel, but the voters rejected that.

The new plan seeks to avoid that debate by simply not allowing private access via Olive Drive and, despite claims to the contrary, the baseline features pretty much preclude a private Olive Drive access to the site.

That directs all of the traffic to campus. The site does accommodate about 700 vehicles with parking spaces, but those who argue this will lead to congestion on campus need to remember that the peak flow of traffic during the week will be from students coming to campus, and most of those students will walk, bike or use the bus – they will not drive. The campus travel survey shows that people who live within a mile from campus do not drive to campus.

Furthermore, this should help alleviate traffic congestion. These 2200 students are already attending class but, instead of driving in from out of town, exiting at Richards and driving onto campus, they are walking and biking to campus.

The more housing we build near campus, the less students will drive to campus and the less congestion we will have.

That means reduced traffic congestion. That means reduced VMT (vehicle miles traveled). That means reduced carbon emissions.

No one seems to following this string but it is critical. The reason why traffic is so bad in the morning and evening commute is that we have 28,000 people commuting into town to work, just as 21,000 commute out of town to work. Building housing next to campus will alleviate some of that congestion.

Does that mean that 700 students won’t be driving at some point? They will. But what people seem to forget is that most car trips are either clustered during peak hours or they are spread out throughout the day. The former are what to contribute to congestion and those will be either zero or close to zero due to proximity to campus.

The latter are going to add a few cars here and there but not be noticeable.

Affordable Housing

The other key reason why Nishi lost is the lack of affordable housing on the original project. This time, they have not only included affordable housing, they have designed it so that students can, for the first time, have access to that housing.

The projected cost for a bed at Nishi will be right around $800 to 900 a month – which is right around market rate. That’s actually pretty good for a new unit. And as we have pointed out, it is much better than the cost of just a bed on campus – which is about $950 in a tiny room with no living room or private living space.

The real advantage is that low income students will be able to apply for rents that start in the $500 range and end up just below $700 per month.

We can go back and forth as to why the developers only provided for 15 percent of the units being affordable, but most students see this as a huge positive for the project.

Housing insecurity is a huge problem. Campus surveys show as many as three percent of all students suffer from housing insecurity. There are students sleeping in the library. There are students living in their cars. And perhaps most frequent are students living on couches or crowded into a common living space due to lack of housing and high costs for rents.

Nishi addresses these issues by adding rental housing capacity which will reduce demand and alleviate the market crunch, while at the same time provide housing for students who are low income.

Are there other reasons to vote for Nishi? Yes. We have mentioned some of them, but for me the three biggest are adding supply during the housing crisis, the alleviation of traffic congestion by putting housing next to campus, and providing low income students with low cost housing options.

We have spent so much time talking about the imperfections of the project, so it seemed necessary to circle back to its core strengths.

Is this enough reason to support the project? That is for you to decide.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

David Greenwald said . . . “First and really foremost is we have a student housing crisis.”

What you are doing with that statement David is attempting to create political spin. Earlier this year I heard the following Perspective segment on KQED, which resonated for me at the time and continues to resonate now. I just replaced the name of the original issue with […] and it applies to our current housing situation in Davis. I have highlighted with capital letters two passages for emphasis.

Matt

I disagree with the KQED commentator. Housing hasn’t been in a crisis, even the Bay Area, for “decades.” When the Internet boom crashed in the early 2000s, housing problems were alleviated there. And even in Davis, it was less of a problem. And again in 2008, the housing issues eased. And now we’ve let a lingering problem fester into a crisis. May an economic crash will get us out of this again, but why bet on that?

Richard, the commentator wasn’t talking about housing, which is why I put in the […]. His comment was on another subject, but for me his observation resonated vis-a-vis housing here in Davis. His “decades” related to the other topic, but with that said, I suspect that some research I am doing, will show that the apartment-rental housing situation we have here in Davis has indeed been in place for at least 20 years. I know it existed when I arrived in 1998, and it hasn’t gotten any better . I’ve put the information request in to UCD for the raw data, and will be meeting with them this coming week to discuss preliminary findings.

Here’s a question for you … your point about the crash of the Internet boom definitely applies to Single Family Residences (SFRs), but does it apply to Multi-family Residences (MFRs)?

“What you are doing with that statement David is attempting to create political spin. ”

I’ve been using the term for probably two years – you’re only objecting now. Political spin? 3% of students are housing insecure l that a crisis.

It is not a crisis. It is the status quo.

To clarify “zero” means that because people are close to campus they won’t drive anywhere, e.g. to or from a job not on campus? And the combination of 700 cars + free parking in Downtown with restrictions and without restrictions in much of the rest of the City will “not be noticeable”?

I’m not following your point. Downtown has two hour parking, you’re suggesting people at Nishi will drive from nishi to downtown to park?

David, it’s one mile from not quite the far end of Nishi to 3rd and F. Not everyone rides a bike. Every unit has about one car on average, which makes it easy to share a car journey if just one roommate doesn’t ride a bike. Do you ever check out the number of bikes at Trader Joe’s/University Mall. , the Marketplace, Food Mart, East Covell Nugget, Grocery Outlet, the Co-op, Target, Mace Nugget, South Davis Safeway? And that’s just markets…. there’s anywhere from 1 to 20% bikes, but the mean is much closer to 1 than 20. If it’s around 5% it’s 1/6 of the goal for 2020. Really only University Mall and the Co-op consistently perform well.

Campus-bound people and junior high students make the cycling-to-work modal share in town. Because either parking is expensive or they don’t drive themselves. High school students ride bikes half as much as they did in junior high, because there’s free parking at DHS. Everyone who pays for parking at Nishi – it’s not bundled with rent, right? – still wants their car, and they will use it. I live near Pole Line and Loyola, on a relatively popular bike route. I have a few roommates. One drives Downtown, takes the bus to campus, never rides his bike. Another rides occasionally, but shops by car. Another has a girlfriend who has a car and no bike and they obviously always go places together by car, and sometimes by foot. Our next door neighbors on one side are all students: No one ever leaves by bike. We’ve had one or two medium-sized student parties here and one or two much wilder ones next door with almost no bikes parked in front.

Good question.

David, you wrote: “If I have a criticism of Measure R – which I continue to support – it is first and foremost a politicization of the planning process which means that (A) positive aspects of the project are overlooked and negative aspects are emphasized, and (B) the need to put forward a project that can pass means that best practices may be ignored in favor of the art of the possible.”

Well, you’ve just described why Measure R does NOT work–it overly politicizes the approval process, which in turn drives away precisely the developers that we desire who are willing to take other project risks to gain sustainability and social justice. Those efforts cost money, but if they face a higher up front cost and higher approval risk, they are much less likely to come to Davis when other communities offer a lower risk. We need to take the decision out of the hands of the people who won’t make the effort to become well enough informed about a complex set of issues.

I agree with David that Measure R works… it works well… as a tool for those that want to prevent development from happening around the city.

The part that does not work is that it causes the lack of housing to become a social issue rather than simply a supply and demand business mechanism.

More complex than that… it also leaves engineering and planning calls to folk who are clueless on either…

More like a “beauty contest”, than rational…

Would you sell t-shirts with this text on them at Farmers’ Market? Would be a nice contrast to the “Love your [every kind of] neighbor” signs, which are implicitly also about educating one’s neighbors.

Interesting point. In design there is this balance requirement of form and function. They sometimes tend to conflict with each other like ying and yang. I think you are right that with Measure R we have unqualified people put in the role of designer… seeking a personal aesthetic end instead of of greater utility for the whole.

There is that saying “lead, follow or get the hell out of the way.” With respect to material change there are generally few visionaries and many critics. Measure R gives way too much power to the critics and emasculates the visionaries.

Measure R is a lab experiment example for why direct democracy does not work.