The final results are in and Measure J not only won, but won overwhelmingly by a 60.5 to 39.4 percent margin. The Vanguard has analyzed the precinct level data and found that one of the keys is that the core which had voted overwhelmingly against Measure A now flipped to, in many cases, heavily support Measure J.

Making this result all the more remarkable is there really is no evidence that students came out in large percentages to the polls. In fact, to the contrary, it seems the student vote – despite heavy efforts by groups like the Measure J campaign, the College Democrats, ASUCD and the Eric Gudz campaign – was relatively low.

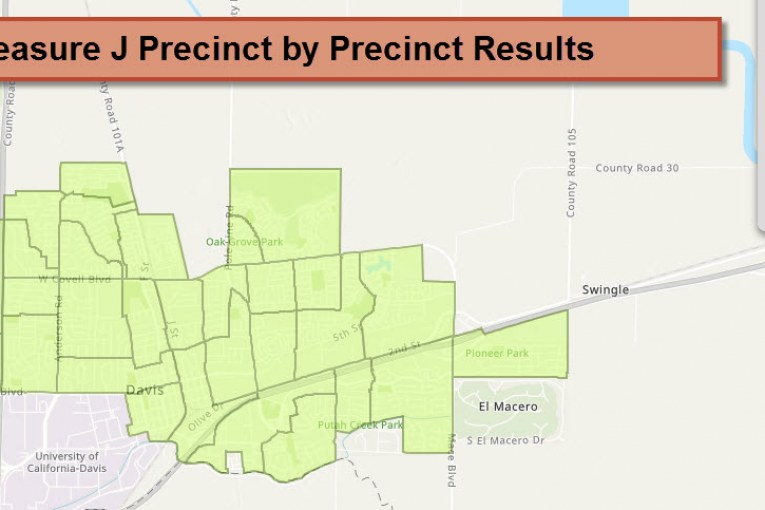

In 2016, when Measure A lost by just about 700 votes, Nishi lost 21 precincts and won just 13. The landscape massively shifted in 2018. Measure J won every single precinct in the city, 18 of them with more than 60 percent of the vote – including 10 of those which had previously voted against Nishi in 2016.

The heart of the city, which had heavily voted against Measure A in 2016, swung heavily, for the most part, by 15 to 25 percent in favor of Measure J.

A key question is what accounted for this rather drastic change in the landscape.

Opponents of Measure J have put forth the argument that the developers simply bought the vote. They will point out that the developers spent over $250,000 attempting to pass Measure J. My problem with that explanation is that in each of the three previous ballot measures involving a Measure J or Measure R project, the developers spent as much or more than they did this time. In 2005, the Yes on Measure X campaign spent more than half a million and yet lost 60-40.

The proponents of Wildhorse Ranch in 2009 spent over quarter of a million and lost 75-25 on Measure P. And of course, in 2016, the proponents of Nishi spent over $300,000 and lost by 700 votes. Clearly, money is not the key variable to explain the change. In each previous case, opponents of the measure were heavily outspent.

I am not going to dismiss the money factor, as clearly the campaign was built around the availability of resources, but just as clear, money itself does not explain why Measure J succeeded where the three previous projects failed.

I am going to argue that there were four key factors that explain the outcome.

First of all, while you can argue Nishi 2016 was superior, Nishi 2018 addressed the two main reasons why Nishi 2016 lost. The developers made the access to be on-campus only, which removed the concerns about traffic impacts on Richards Boulevard. The developers also addressed the issue of affordable housing, which badly hurt the 2016 effort. They created an on-site, student-based affordable housing program.

You can also argue that, although opponents continually raised the issue of air quality, by making the site rental housing for students the developers limited the impact even of that issue. Although it was not for lack of the opposition trying.

At the outset, we believed, based on those three changes alone, Nishi ought to win and win easily. And I would argue it eventually played out that way. Several of the weaknesses of the No campaign were due to the fact that they simply did not have that much to work with.

Second, whether you want to argue that the student housing crisis worsened in 2016 or that the perception did, the fact remains that the political landscape shifted markedly in two years. The Vanguard hammered home the point that we were in a student housing crisis.

The Enterprise in their editorial didn’t use the term crisis but called Nishi “a remarkable effort to meet the biggest need in Davis, the thousands of UC Davis students who cram into single-family homes all around town.”

Some opponents tried to argue it wasn’t a crisis, claiming that a long-running problem is not a crisis. While I disagree, those are primarily semantics. What isn’t semantics is the fact that students are cramming into houses designed to be single-family homes, there are students who are housing insecure, students living on couches, in cars, sleeping in the library.

The discussion shifted in two years, and the fact that the Nishi project focused exclusively on the biggest need in this community certainly did not hurt the project.

Third, the opponents of Measure J just ran a bad campaign. If you want to argue that the opponents just lacked the material to mount a credible attack on the project, I think you are correct. That would seem to suggest that maybe they should have just conceded electoral defeat.

From the start, we suggested that a problem with the opposition was that the one real issue they had was air quality. We didn’t see that as sufficient to drive a significant no vote because it lacked the self-interest component that issues like traffic have had in the past.

As many are aware, I dispute many of the claims by the opposition on the quality of the air. It is not that building next to a freeway is ideal, but we do need to put it into perspective. The developers were willing to take mitigation measures to address some of the impact. You can argue those mitigations won’t be as effective as the developers claim – but, given that a lot of the impact studies are based on older and less mitigated projects next to a freeway, it is a factor.

In the end, we believed that a combination of short duration, vegetation, air filtration and pressurizing of the buildings would reduce impacts on health. We are also far from convinced that Nishi was really that much worse than other locations, and I think most people in the community saw the efforts to push for more study as an effort at delay.

Once the air quality issue was blunted, it left the opposition with very little to hit on.

As one observer put it: “What if the no people made a few arguments that were so lacking in credibility that it swung the election to ‘yes’?”

I don’t know if I would go that far, but some of the arguments just lacked credibility.

You had the claim that Nishi was going to lose $350,000 to $700,000 a year. I don’t care how many charts someone lays out, a lay person examining that argument is going to say that this is basically an apartment complex, how in the world does it lose that much for the city? It didn’t pass the smell test.

Then you have the litany of weird red herrings that sounded absurd and more than desperate. I think the average person listened to this stuff and discounted it as an attempt to throw everything against the wall and see what stuck.

At the end of the day, there appears to be a solid 38 to 40 percent of the voters who are going to vote against every project. There is a much smaller number that will vote for most, if not all, projects. I would then estimate a malleable middle of somewhere between 20 and 40 percent of the voters. It appears that Nishi captured most of that malleable middle and that the opposition got just about the core No vote and little else.

Did money drive this result? Again, I won’t discount money. You have to get your message out to the public, even in a relatively high information environment like Davis. But I think the facts are what led to this outcome and the opposition to Nishi basically had one real argument: I’m against housing at Nishi.

To the credit of the voters, the kitchen sink approach did not work this time. To the detriment of the opposition, they tried it and I think they hurt their credibility going forward.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

> The Vanguard hammered home the point that we were in a student housing crisis.

There’s your answer.

“the point that we were in a student housing crisis”

I agree that the majority of voters saw the issue this way. I heartily applaud the community for stepping up to address a major need whether one likes the word “crisis” or not. I would also add that in this instance, Measure R worked exactly as intended demonstrating that is possible.

Once

I wouldn’t discount the impact of disconnecting the project from Olive Drive/Richards. I think a high percentage of the voting population is aware of the congestion there and don’t want to see it get worse. Once that was out of the way, I figure that most voters don’t really care what happens on the Nishi property — they see the development as not hurting them, and maybe even helping a little.

Jim, as for my vote (and 2 others in our household), you nailed it…

Good observation… sturdy frames need good nails… (sorry, too easy)

> I wouldn’t discount the impact of disconnecting the project from Olive Drive/Richards.

I almost didn’t vote for 2.0 for that reason . . . and every person I’ve asked so far, same (saw the connection as a benefit to divert traffic off First Street).

Another factor is that the city only presented the positive fiscal model (which had no actual basis for the 75% cost allocation), and disregarded the analyses from two finance and budget commissioners, which showed ongoing deficits. Unfortunately, an external fiscal analyst was (also) not used, for Nishi 2.0.

In other words, voters were not presented with complete information (for Nishi 2.0), by the city. (A decision made by some of the same folks who claim to be concerned about fiscal issues.)

I don’t agree. There was enough discussion in the community and on the ballot statements about the fiscal impact. I don’t think most people found the claim of $350 to $700 thousand deficits credible and I also don’t think most people vote for projects on the basis of fiscal analysis.

The Salomon analysis was more nuanced, than Matt’s.

It’s truly unfortunate that an external analyst was not used, for Nishi 2.0. (Of course, city officials might still have chosen to disregard it.)

But – maybe you’re right regarding voters’ apparent willingness to add to the deficit. Of course, we’ll never really know the actual fiscal impacts, since it will be blended into the fiscal hole. (Which you’ll then refer to it as the “city’s problem”.)

You say their willingness to add to the deficit, I would argue most people don’t believe an apartment complex is likely to do that.

Calling Nishi an “apartment complex” is like calling a great white shark a “fish”. (If I come up with a better analogy, I’ll let you know.) For example, do most apartment complexes in the city have 700 parking spaces?

Existing development is already not providing sufficient funds to pay the city’s bills.

Wasn’t it Einstein who said that doing the same thing over-and-over, but expecting different results is the definition of insanity? (Actually, that might apply to discussions on the Vanguard, as well.)

Regarding Howard’s comment, I’d have to agree. When the city – in conjunction with developers repeat the same incomplete (and misleading) information, folks tend to believe it. (Perhaps applies to the air quality concern, as well.)

[edited]

In any case, I haven’t seen anyone try to justify the 75% across-the-board allocation, used by the city for their Nishi fiscal analysis. I don’t recall if they used that percentage (which has no apparent basis) for every single cost category.

So, we should go with what amounts to minority views? Should minority views become the “new normal” for action? I have no doubt that the minority views were fairly considered… yet…

And it’s not like the minority view didn’t come out.

This is from the ballot statement against Measure J: “The project design will saddle the city with more costs than revenues. That means the rest of the community will subsidize the financial shortfall of this project, imposing costs onto our community.” So I’m not sure what Ron believes the impact would have been when the argument was out there and used extensively by the No on J campaign.

Pretty sure that the “majority” disagreed with the external analyst (for Nishi 1.0), as well. Of course, that “problem” was averted this time, since they didn’t even use one.

Still wondering how the majority defends this:

David: There’s a difference regarding statements from the city, itself.

David, et al. re: your 9:57 post…

From the movie,the King and I, truly,

“It is a puzzlement”…

“Calling Nishi an “apartment complex” is like calling a great white shark a “fish”. (If I come up with a better analogy, I’ll let you know.) For example, do most apartment complexes in the city have 700 parking spaces?”

It’s a big apartment complex, but it’s still an apartment complex.

Of the people I know that flipped to vote yes vs. no in the past the main reason was the hope that it will reduce the number of kids living in the neighborhoods.

Basically I think more people in town hate “mini-dorms” (homes with converted living rooms and garages with six kids living in them) more than “mega-dorms” (apartments with 3 and 4 bedroom units with six kids living in them)…

Most voters in town would rather have the kids playing beer pong, making noise and puking in the bushes on the Nishi site then in their neighborhoods.

“I think more people in town hate “mini-dorms” (homes with converted living rooms and garages with six kids living in them) more than “mega-dorms” (apartments with 3 and 4 bedroom units with six kids living in them”

Interesting point. I still don’t really understand why people care that much about “mega-dorms” it barely impacts them.

> I still don’t really understand why people care that much about “mega-dorms” it barely impacts them.

VERY SCARY

Vague one-liners are difficult to dicepher.

> Vague one-liners are difficult to dicepher.

I resemble that remark.

Why NIshi passed?

> There was no near-neighbor impact, so there was no core of self-interested opponents.

This is why I believe I am collecting $50 worth of cactus.

The primary reason that Nishi #2 passed is that the topic of Davis housing has moved into a social justice space. Daivs is filled with voters that decide primarily through a filter of fairness and harm. That is why people like Tia Will would be against Trackside and not Lincoln 40. She can accept more tenement housing for the needy little people, but does not support adding housing that fits the need of someone else she perceives as being well off.

Although it was clearly important to some voters, I don’t agree that the traffic concern differences between Nishi #1 and Nishi #2 were material in the outcome… but I could be wrong. It certainly did not influence me nor my neighbors who thought the Richard’s intersection changes were needed and beneficial.

I was hoping there would be some comparative analysis of previous campaigns with a breakdown of comparative proponent/opponent spending. Without that, you could have saved a lot of words by just saying:

1) the project is literally in no one’s backyard (primary messaging of the campaign).

2) the project promised “affordability” with a cynical bait-and-switch (and highly profitable) bed lease scheme (secondary messaging).

[side note: after I published extensive analyses exposing the project “affordability” for the fakery that it is, the project actually changed its most deceptive statement on the campaign website]

I see no particular reason to believe that ‘affordability’ was a salient issue to most Davis voters.

There is a comparison of proponent spending in this article, which is helpful to show that there was no additional (or even less) spending on that side this time, so that argument can be dismissed. As for the opponents, the key was that they didn’t have a particularly adept individual working for them this time. He sat out this campaign.