The parcel tax proposal puts many in this community into a quandary. On the one hand, the school district is disadvantaged by LCFF (Local Control Funding Formula) funding which has in part, even with the parcel tax in place currently, meant that teacher compensation, meager as it is in most communities, lags behind comparable districts by a sizable margin.

On the other hand, the ballot measure, proposed by board member Alan Fernandes, at $365 per parcel per year, has some unintended consequences even if it manages to get on the ballot. The community is going to have to think long and hard about whether this is the right remedy to the teacher compensation problem.

Twenty-five percent “of the annualized proceeds must be used by the City for hiring an additional school resource peace officer and increasing emergency first responders consistent with Chapter 13 of the City’s Municipal Code,” the measure stipulates.

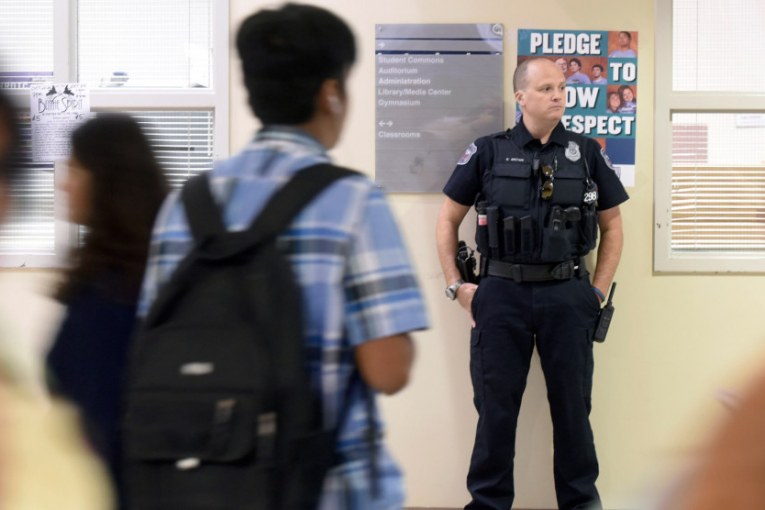

My biggest concern is the consequence of putting another police officer on campus. Interestingly enough, Chief Darren Pytel told Alan Fernandes that he doesn’t want a second school resource officer (SRO).

The research is not good on the presence of SROs on school campuses.

But we don’t have to look far to see the problem in our own schools. Back in the summer of 2011, the Vanguard covered the case of a Davis High School student who was pulled out of her class at Davis High in front of her teacher and all her classmates, and escorted by a school staff member to the office of the head campus supervisor where she was questioned by a Davis police officer. (see DHS Student Describes Being Threatened By Police, Betrayed by School Staff, August 22, 2011).

The story was simple – the student had written a story for the school newspaper, the Davis HUB, on graffiti. In fact, the student served as editor-in-chief of the paper. She told the Vanguard that  she did not expect any issues, believing that if she did not disclose any names, no one would get into trouble.

she did not expect any issues, believing that if she did not disclose any names, no one would get into trouble.

But, instead, she was pulled out of class, not told why, and made to wait in a room while the vice principle, campus supervisor and SRO walked into the room.

She told the Vanguard, “He said, ‘This is a very serious matter, you need to comply with what I ask you to do. If you don’t, there will be very serious consequences.’ And then he began asking me a lot of questions.”

This was not a friendly conversation. From the start, the officer was threatening her with very serious consequences should she not comply.

“He was doing his job. I understand that this officer was simply doing his job and I get that,” she said. “But he coerced me, he intimidated me and he lied to me.

“I said I was sorry. I [had] explained to these individuals that I would not give out their names. I gave them my word. I won’t go against my word,” she explained. “I know that I’m a student journalist and that I have First Amendment rights. I’m not going to disclose these people’s names.

“As soon as I said that, he began telling me that I would be liable in court, that the court would easily force me to give their names and that I would have a felony charge on my name,” she said.

At no point did she think to ask for an attorney. Instead, “As he was telling me these things, I just continued to apologize and say I’m sorry I can’t help you, but that wasn’t good enough. He continued to work me and continued to intimidate and threaten me.”

The student here was actually quite fortunate. While the ACLU would file a suit in her case, she did not end up criminally charged and she also stuck to her guns, not cooperating with the police.

Since the 1999 Columbine High School shooting, there has been concern by civil rights advocates who believe that, rather than creating safer campuses, officials have facilitated the school-to-prison pipeline by effectively criminalizing behavior that should have been handled as more basic discipline issues.

A 2015 article by US News cites: “Thanks to inconsistent training models and a lack of clear standards, critics contend school officers are introducing children to the criminal justice system unnecessarily by doling out harsh punishments for classroom misbehavior.”

“Is this is an effective intervention strategy? It’s really not having the impact we want to have,” said Emily Morgan, a senior policy analyst at the Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center, a nonprofit that works to strengthen public safety and communities.

“School policing is tied to that broken windows, tough-on-crime era, when we were all panicked about the juvenile supercriminals that were going to start running the streets,” said Deborah Fowler, executive director of the advocacy group, Texas Appleseed. “They didn’t emerge, obviously.”

The ACLU in 2017 released a 95-page report: “Bullies in Blue: The Origins and Consequences of School Policing.”

The biggest problem they cite is that “the scrutiny and authority of law enforcement are turned upon schoolchildren themselves, the very group that’s supposed to be protected.”

The problem is that introducing police onto a campus results in the criminalization of young people for matters that traditionally have been handled better as school discipline.

The ACLU is concerned that such practices have “justified the targeted and punitive policing of low-income Black and Latino youth.”

This started as a response to the war on drugs and gang interdiction efforts, but it has been expanded in the post-Columbine world.

The ACLU writes, “Later, fears of another Columbine massacre misguidedly drove the expansion of infrastructure that ensured the permanent placement of police in schools. As this report outlines, the permanent presence of police in schools does little to make schools safer, but can, in fact, make them less so.”

School Resource Officers are police officers and they are specifically identified as part of the problem: “[P]olice officers assigned to patrol schools are often referred to as ‘school resource officers,’ or SROs, who are described as ‘informal counselors’ and even teachers, while many schools understaff real counselors and teachers.”

They add, “Their power to legally use physical force, arrest and handcuff students, and bring the full weight of the criminal justice system to bear on misbehaving children is often obscured until an act of violence, captured by a student’s cellphone, breaks through to the public. Police in schools are first and foremost there to enforce criminal laws, and virtually every violation of a school rule can be considered a criminal act if viewed through a police-first lens.”

Moreover: “The capacity for school policing to turn against students instead of protecting them has always existed, and it continues to pose a first-line threat to the civil rights and civil liberties of young people.”

A 2015 study published in the Washington University Law Review found that, since the shootings at Sandy Hook and elsewhere, ” lawmakers and school officials continue to deliberate over new laws and policies to keep students safe, including putting more police officers in schools.”

However, they found, that “these decisionmakers have not given enough attention to the potential negative consequences that such laws and policies may have, such as creating a pathway from school to prison for many students.”

Traditionally, only educators, not law enforcement, handled certain lower-level offenses that students committed, such as fighting or making threats without using a weapon. The study found that “a police officer’s regular presence at a school is predictive of greater odds that school officials refer students to law enforcement for committing various offenses, including these lower-level offenses.

“This trend holds true even after controlling for: (1) state statutes that require schools to report certain incidents to law enforcement; (2) general levels of criminal activity and disorder that occur at schools; (3) neighborhood crime; and (4) other demographic variables.”

They write: “The consequences of involving students in the criminal justice system are severe, especially for students of color, and may negatively affect the trajectory of students’ lives. Therefore, lawmakers and school officials should consider alternative methods to create safer learning environments.”

The biggest concern is that these policies will widen an already huge racial divide.

For example, in Broward County, Florida, where Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School resides, black students only represent 22 percent of the school population, but received 71 percent of the out-of-school suspensions.

Governor Rick Scott voiced opposition to arming teachers, but instead proposed adding one school resource officer for every 1,000 students.

DJUSD already has problems both with an achievement gap and a discipline gap, where students of color, specially black and Latino students, have traditionally been far more likely to be suspended than white and Asian students.

Adding another SRO in our schools is a recipe to bring more students of color in closer proximity to law enforcement, where research repeatedly shows that is not a good idea.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

DHS Student Describes Being Threatened By Police, Betrayed by School Staff

As I’ve understood it for years, the existing SRO has done a great job and is well respected pretty much by all… are you proposing reduction of the existing position, or just not adding a new one?

Sounds like the Chief is suggesting the latter, not the former.

Obviously I am going to look for a source that supports my view that even one police officer enforcing the law in a special and sacred space that is key in the formation of good and loving humans is a bad idea:

“Schools should employee peacekeepers, restorative justice coordinators or intervention workers instead of SROs, according to DSC guidance. Staff members should be trained in positive approaches to school climate and discipline, de-escalation techniques and conflict resolution. Schools should intentionally recruit administrators and teachers of color to make sure staff demographics accurately mirror the community they serve.” from this source.

But it’s a bit deeper than that, isn’t it? The issue is more fundamentally the normalization of militarization – city police are municipal military – of these sacred spaces. It’s already bad enough with active shooter drills inside, and outside the school, constant war that itself takes billions away from the public education system, or cynically rewards participation in this war with free education after high school, a sub-structure based in racism since it’s non-White people who disproportionately need help for college.

35 or so years ago I attended a very diverse high school in an independent city inside Los Angeles. Sure, there were problems, and many dealt with discretely by internal staff, possibly with help from the local police department from time to time in various serious cases. But an in-school cop would have not been tolerated; it would have a been the subject of constant, distracting controversy. I have a feeling that most people around my age or older who also attended public school in the USA have the same opinion.

Having graduated from a very large inner city high school with a very diverse population of students in 1970, I agree. Seeing police in the school of 2000 + was a very uncommon event. So much so that the presence of even one officer was sure to draw a crowd of curious students. I truly dislike the militarization of our current society.

Strongly suggest you get a copy of SRO’s job description, meet with him, have him walk you through what he does, what he doesn’t do, and talk to the teachers, administrators, and (if you can) parents and/or students who have interacted with him over the years…

Then tell Todd, Tia, the rest of us your impressions as to your informed impressions as to whether he is a “military presence”…

Howard, the point I am trying to make is that all of this… oh I already said it: “normalization”. They want everyone to be comfortable with a person present who is not really a social worker and has a gun. It’s nice that the current campus cop is what you say he is, so maybe he should retrain as a social worker or nurse?

Thought it was clear, Todd, that I was directing my suggestion to David… bet a lot that you have not seen the job description, met the officer, staff, nor administrators on the subject… so an uniformed “conviction”… which, is a “normalization” of a sorts…

Indeed, my point was the article lacked investigative reporting, but, as the title said, it was “view”, and not a “report”… I suggested taking it to the “report” level…

We are idiots to ignore the security threats derived from our previous idiocy to change policies and fill our cities with so many people owning mental health problems that would otherwise be institutionalized.

Oh wait… we don’t ignore the threats… for government buildings… other than for our schools.

I guess we are only half idiots.

The SRO is not there primarily for “security”… the title, S = schools (not police nor security), “R” = “resource”, “O” = officer, meaning someone trained to help advise teachers/administrators (as a resource) as to what actions they might consider or reject…

I went to a high school with a 39% graduation rate and an awesome basketball team.

It’s irrelevant though. The idea that we are going to vote for a parcel tax to to finance a position we have not discussed having in the first place is ludicrous. Probably seemed like a good idea to whomever in the firefighter union drafted the measure.