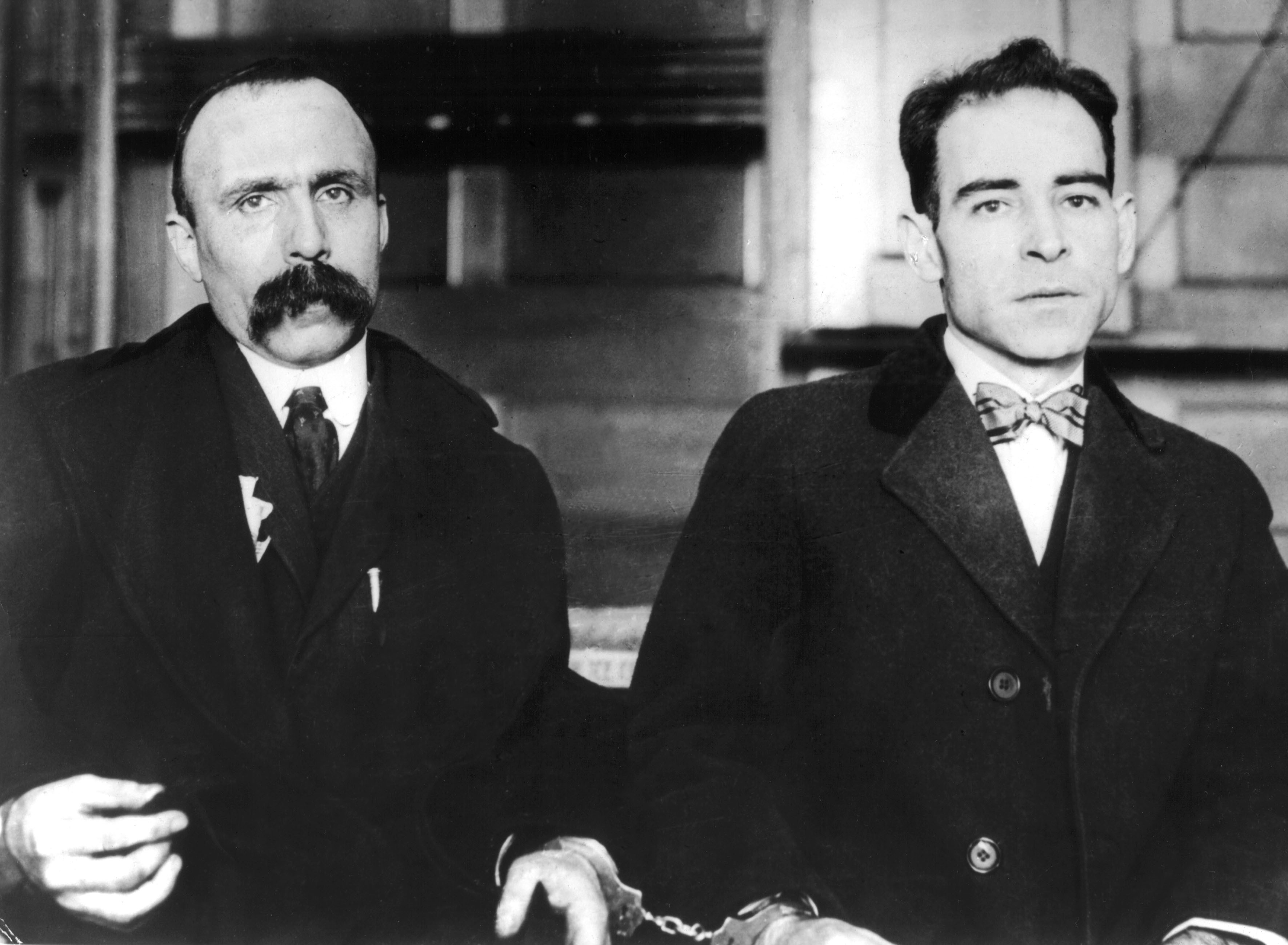

Over the holiday break, one of my books I am reading is the case of Sacco and Vanzetti in 1921. At the height of the red scare and following a series of high profile bombings, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, both Italian-Americans, were convicted of robbery and murder.

Reading this history as a wrongful conviction case, many of the key elements line up with problems of any conviction – reliance on problematic eyewitness identification, bad forensic work on the ballistics, a biased judge who conducts a fundamentally unfair trial, tunnel vision leading prosecutors to ignore more likely suspects, prejudice against the defendants leading to ignoring things like alibi evidence and possible alternative suspects, and a legal system deciding that the rulings were within the trial court’s discretion and therefore being unwilling to throw out the verdict and order a new trial.

The evidence against the two was thin, but of course they didn’t help themselves by telling the police a number of lies that were easily disproven and cast suspicion on them, even as the evidence did not align. Mr. Vanzetti would claim that he had simply attempted to avoid naming fellow anarchists and friends.

In the end, there is of course uncertainty in this case, as author Bruce Watson points out in his 2007 account of the cause célèbre trial. No one can explain what the two men were up to the night of their arrest and, “no matter how much one wants to shout their innocence, questions remain.”

But looking at this case with fresh eyes, knowing what we now do about wrongful convictions, this one lines up rather classically.

They had a myriad of witnesses – some claiming to have seen the men, some changing their story under pressure from investigators and the prosecutor, and others coming out to testify for the defense. In a lot of ways this hinged on eyewitness identification and it is here that we see a huge red flag.

As Felix Frankfurter, a future Supreme Court Justice, wrote in the Atlantic: “The inherent improbability of making any such accurate identification on the basis of a fleeting glimpse of an unknown man in the confusion of a sudden alarm…”

Key evidence for the jury was matching the bullets to a weapon that was owned by Sacco. However, as we now well know, the science of such bullet matches is questionable at best. And, even at the time, there was conflicting expert testimony as to whether it was true.

For instance, after the fact, one expert said, “Had I been asked the direct question whether I had found any affirmative evidence what ever that this so-called mortal bullet had passed through this particular Sacco’s pistol, I should have answered then, as I do now without hesitation, in the negative.”

Prejudice and tunnel vision played a huge role here. The public outcry pushed the Governor of Massachusetts to form a committee to do an inquiry as to whether he should pardon or commute the sentences – it was a highly respected committee that included the Harvard President.

And yet, to no avail.

The governor, for instance, demanded to “see documentary evidence on everything,” but then discounted the alibi. Mr. Vanzetti “claimed he had been selling eels during the Bridgewater burglary. Where was the proof?” When told there were 16 witnesses who swore they had bought eels, Governor Fuller responded, “those are Italians. You can’t accept any of their words.”

I also found the response from the esteemed jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes fascinating – at the last moment, even he, one of the most respected jurists in our nation’s history, refused to intervene.

“Prejudice on the part of the presiding judge, however strong,” he said, did not give him authority “to interfere in this summary way with the proceedings of the State Court.”

It was flooring, what he said.

He told the attorneys intervening on behalf of the condemned that Sacco and Vanzetti “did not get a square deal,” but said he “could not toss aside the separation of state and federal courts.”

Later, Justice Holmes’s secretary asked him whether justice had been done. “Don’t be foolish, boy,” Mr. Holmes answered. “We practice law, not ‘justice.’”

Change a few of the background details and the Sacco and Vanzetti case fits well with what we see today with wrongful convictions.

As the late Antonin Scalia once wrote, “[M]ere factual innocence is no reason not to carry out a death sentence properly reached.”

That may well have summed up the Sacco and Vanzetti case.