The question of wrongful convictions is a vexing one. The best data and research seems to be in the area of death penalty cases. Death penalties cases are both a good and bad test area for exposing wrongful convictions overall in the system. They are good because there has been a lot of scrutiny and focus on death penalty cases. Appeals are automatic. Data is prevalent.

The question of wrongful convictions is a vexing one. The best data and research seems to be in the area of death penalty cases. Death penalties cases are both a good and bad test area for exposing wrongful convictions overall in the system. They are good because there has been a lot of scrutiny and focus on death penalty cases. Appeals are automatic. Data is prevalent.

On the other hand, the death penalty cases also expose the most biases in the system. For instance, the difference between whites and blacks receiving death sentences is far greater than the white versus black discrepancy in the overall criminal justice system.

For those of you who believe the problem with the death penalty system is that it takes too long to execute people, these studies should at least give you pause.

Racial disparity studies in death penalty cases are not new. In the 1980s, the Baldus Study came out with an exhaustive study of more than two thousand murder cases in Georgia. That study found that defendants charged with killing white victims were 11 times more likely to end up with the death penalty than those defendants charged with killing black victims. The gap in Georgia was huge. In 70 percent of cases with a white victim and black defendant, prosecutors sought the death penalty. The inverse was only true about 19 percent of the time.

Nearly 25 years later, the system has not changed much. In 1987, the Supreme Court ruled in McCleskey v. Kemp that racial bias in sentencing, even that which could be shown through credible statistical evidence, could not be challenged unless they could show clear evidence of conscious discriminatory behavior. However, leading the way to attempt to change things is the state of North Carolina.

Now, in North Carolina, a law was passed that will allow those facing the death penalty to present evidence of racial bias, including statistics in the court. “A recent comprehensive study on race and the death penalty in North Carolina found that the odds of getting a death sentence increase three-and-a-half times if the victim is white rather than a person of color,” reads a website explaining the act, and citing a 2001 UNC-Chapel Hill study.

A recent study has found that African-American defendants are more likely to be wrongfully convicted of crimes punishable by death. In North Carolina, six of the seven exonerated death row inmates were people of color. There are a variety of explanations for these racial disparities, ranging from deliberate racial stereotyping ranging, to the perceptions of jurors and law enforcement that African-Americans are more “prone to violence,” to unconscious racism.

One study, for example, found that witnesses are far more likely to misidentify perpetrators of different races than their own race, even if they hold no conscious racial prejudices.

There are other problems as well. For instance, in North Carolina, a government audit showed that a crime lab had tampered with evidence and issued false reports in over 230 criminal convictions, including capital cases.

Seth Edwards, president of the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys, said that he supported a moratorium on the execution of any death row inmates whose cases include evidence from the State Bureau of Investigation. “[W]e need to make sure the issues are resolved in the SBI crime lab,” Edwards said. “I just feel like the public right now is skeptical.”

The Greensboro, North Carolina, “News and Record” had an editorial on Wednesday talking about the last executed person in North Carolina, who was put to death in August of 2006.

“It’s possible Flippen forever will remain the last person executed in North Carolina. The state should make sure of that,” they write. “Capital punishment is on its last legs here. The only question is whether a handful of condemned prisoners will follow Flippen before the end, or whether the practice officially will be brought to a halt.”

“Juries and even prosecutors, by and large, prefer sentences of life without parole,” they continue. “That’s not a soft-on-crime penalty. Locking someone up for the rest of his natural life — often 50 years or more — not only protects the public, it allows for errors to be discovered and corrected. Execution does not.”

Moreover, they write, “Many mistakes have been exposed lately. Not only have innocent men been released from prison when new evidence has surfaced, but recent reports reveal that shoddy and dishonest work was turned out for years by the State Bureau of Investigation’s crime lab. In some cases, false evidence led to wrongful convictions — and possibly executions. On Monday, the president of the N.C. Conference of District Attorneys conceded that executions in affected cases should stop, pending further reviews of evidence.”

North Carolina is not the only state that is questioning Capital Punishment in light of these problems.

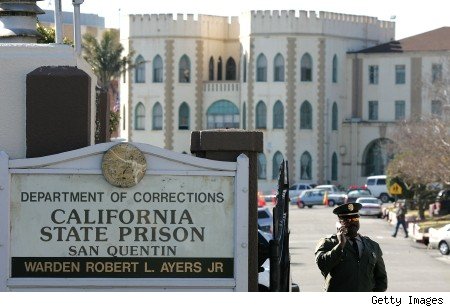

While North Carolina is moving toward putting the death penalty on hold, California officials are attempting to resume executions after a more than four-year hiatus. On Tuesday a Marin County judge put up another roadblock, issuing a ruling that bars prison officials from moving forward with new executions.

“The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation adopted new lethal injection procedures this summer, hoping to resolve state court orders that found the previous rules had been put in place in violation of state regulations, as well as a San Jose federal judge’s concerns that the prior lethal injection method risked cruel and unusual executions,” reported the San Jose Mercury news. “But the new regulations now face new legal challenges.”

“Lawyers for death row inmates filed a lawsuit in Marin County Superior Court, saying they still don’t comply with California rules for enacting new regulations. And U.S. District Judge Jeremy Fogel is now evaluating whether he is free to consider if the new lethal injection procedures, and San Quentin’s new death chamber, address concerns that inmates may suffer inhumane deaths from the state’s three-drug cocktail of lethal drugs,” the article continued.

The now infamous Texas death penalty case should give us pause as to how many innocent people we have executed, and how many more we may eventually execute or imprison.

Cameron Todd Willingham was executed for the arson murders of his children, despite evidence that there was no arson and thus no crime. Governor Perry of Texas actually had the evidence before him that Mr. Willingham may have been innocent, but allowed him to be put to death anyway.

The Houston Chronicle in July published an article reporting on the Texas Forensic Science Commission’s report. “In a report prepared last year for the commission, fire expert Craig Beyler said the original investigation was so seriously flawed that the finding of arson can’t be supported. He said the investigation didn’t adhere to the fire investigation standards in place at the time, or to current standards.”

The article continues, “The commission then appointed a four-person panel to review Willingham’s case. John Bradley, who is chairman of both the panel and the commission, said the panel’s review concluded arson experts in the case did not commit misconduct or negligence.”

Furthermore, “Bradley and panel member Sarah Kerrigan, a forensic toxicologist and director of a crime lab at Sam Houston State University, acknowledged the science the fire investigators used in the Willingham case was flawed. But they said that didn’t translate into professional negligence, because investigators were relying on the techniques and information available at the time.”

Finally, “New fire investigation standards were not adopted until 1992, the same year Willingham was convicted, but it was several years after that before they were adopted nationally, said Bradley, who is also the Williamson County district attorney.”

The Ohio Governor this week avoided making such a mistake, commuting the death sentence of convicted killer Kevin Keith from death to life in prison without parole, at the same time vowing to examine more to determine the possibility that the individual is innocent.

Governor Ted Strickland wrote a release explaining his decision in a manner that demonstrated an unusual amount of forethought and thoughtfulness in his decision-making.

“Kevin Keith was convicted, by a jury, of callously murdering three people, including a four-year-old child, and shooting three others, including two young children. Since the time of his arrest more than 16 years ago, Mr. Keith has maintained his innocence, insisting that someone else committed the murders,” Governor Strickland said in his statement.

“Mr. Keith’s conviction has been repeatedly reviewed and upheld by Ohio and federal courts at the trial and appellate level. The Ohio Parole Board recommended against clemency in this case. There is evidence which links him to the crimes that, while circumstantial, is not otherwise well-explained. It is my view, after a thorough review of the information and evidence available to me at this time, that it is far more likely that Mr. Keith committed these murders than it is likely that he did not,” he continued.

“Yet, despite the evidence supporting his guilt and the substantial legal review of Mr. Keith’s conviction, many legitimate questions have been raised regarding the evidence in support of the conviction and the investigation which led to it,” the governor wrote. “In particular, Mr. Keith’s conviction relied upon the linking of certain eyewitness testimony with certain forensic evidence, about which important questions have been raised. I also find the absence of a full investigation of other credible suspects troubling.”

“Clearly, the careful exercise of a governor’s executive clemency authority is appropriate in a case like this one, given the real and unanswered questions surrounding the murders for which Mr. Keith was convicted. Mr. Keith still has appellate legal proceedings pending which, in theory, could ultimately result in his conviction being overturned altogether. But the pending legal proceedings may never result in a full reexamination of his case, including an investigation of alternate suspects, by law enforcement authorities and/or the courts. That would be unfortunate–this case is clearly one in which a full, fair analysis of all of the unanswered questions should be considered by a court. Under these circumstances, I cannot allow Mr. Keith to be executed. I have decided, at this time, to commute Mr. Keith’s sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Should further evidence justify my doing so, I am prepared to review this matter again for possible further action,” the Governor concluded.

What I find interesting here is that the governor maintains that the he is more likely guilty than not. That is an interesting point because, theoretically, the only way someone should be imprisoned, let alone executed, is if there is not any sort of reasonable doubt. Did the prosecution meet the appropriate burden-of-proof standard for the conviction?

The issues raised by the Governor, in this case, are issues I have often noted in my observations of Yolo County court cases. While none of these cases are death penalty cases, it is vexing to me the ease with which the jury convicts individuals based on sketchy recollections of witnesses, many of whom have biased and self-interested reasons to attempt to incarcerate individuals.

The fact that the overall system is so flawed should give us all pause when we note that an individual was convictied by a jury. All of these individuals who are later exonerated are convicted by juries. Some are convicted based on rather flawed and untested scientific evidence.

About five years ago, CNN had a special on faulty forensic science, highlighting that many of the findings that forensic scientists have maintained as fact were never scientifically challenged. One good example is bullet-lead analysis, which had been admitted in criminal trials without significant challenge for nearly half a century.

These studies were allowed into court, despite the absence of any kind of scientific or legal oversight, scientific reliability or testing of the theory, hypotheses, assumptions and practices.

Bullet-lead analysis is only one example. The use of experts in court testifying to largely untested and unproven matters is a further problem. One example in Yolo County has been the use of gang experts, the individuals who are police officers and who testify about training and expertise they have about gangs. However, reading some academic research on the topic of gangs, it is discovered than many of law enforcement’s beliefs about gangs and gang activities is either flawed or skewed, in part because they only encounter a small subsection of the overall gang population. And yet juries make decisions of guilt and innocence based on untested “expert” analysis.

The Innocence Project has used scientific DNA evidence to overturn numerous wrongful convictions. According to Wikipedia (which must be used skeptically as a source of facts), as of August 2010, there have been 258 people who were previously convicted of serious crimes that have been exonerated by DNA testing. They claim about half involved sexual assault and 25 percent involved murder.

There are several things worth noting, since DNA availability is probably helpful in a small percentage of cases that contain biological evidence that can be used to retest previous convictions. The key question is what these exonerations show us about the criminal justice system. Why were these innocent people convicted, beyond a reasonable doubt, by a jury?

Here are six causes that were found most prevalent. First, eyewitness misidentification. This should not surprise anyone. Eyewitness evidence is extremely unreliable. If you do not believe me, have a group of ten people sitting in a circle, have an individual come in, tap someone on the shoulder, and exit. Then have the group describe that individual.

Second, unvalidated or improper forensic science. We previous mentioned the bullet-lead analysis, but there were a whole host of discredited techniques, illustrated in the CNN special, that apparently no one in the courts wanted to force to be scientifically verified.

Third, false confessions or admissions. There are a lot of reasons for that, as well, including defendants with mental disorders and defendants subjected to varying levels of coercion. “In about 25% of DNA exoneration cases, innocent defendants made incriminating statements, delivered outright confessions or pled guilty,” writes the Innocence project. “These cases show that confessions are not always prompted by internal knowledge or actual guilt, but are sometimes motivated by external influences.”

In addition to people with mental disorders, “Mentally capable adults also give false confessions due to a variety of factors like the length of interrogation, exhaustion or a belief that they can be released after confessing and prove their innocence later.”

Fourth, they listed government misconduct. “Some wrongful convictions are caused by honest mistakes. In some cases, however, officials take steps to ensure that a defendant is convicted, despite weak evidence or even clear proof of innocence,” they write. “The cases of wrongful convictions uncovered by DNA testing are replete with evidence of fraud or misconduct by prosecutors or police departments.”

Fifth, informants or snitches. This is one of the biggest questions we had in the Rudy Ornelas conviction. The prosecutor got Claudio Macobet to testify against Mr. Ornelas, but Mr. Macobet was at the same time a suspect himself, and therefore had a reason not to tell the truth.

Finally is the problem of bad lawyering. We have the famous example of defense attorneys who fell asleep in the courtroom in Texas and that was not reason enough to overturn a conviction. We have also discussed the differential in resources that the DA’s office has versus the public defender’s office in Yolo County. The bad thing is that Yolo County’s indigent defendants get better representation than many.

The real problem is that, while they have been able to use DNA to overturn 258 convictions, we know full well that non-DNA cases suffer from the same problems.

When you consider that perhaps ten percent of people are in prison who were innocent and you also consider that most cases never go to trial, you recognize that in a large percentage of cases, a jury finds innocent people guilty.

That does not mean that the jury gets it wrong, as they can often only weigh in on what they are shown. But for those who argue somehow that a guilty finding by a jury is the end of the story, think about all of the people that were, in fact, not guilty but were convicted.

Yolo County has its own unique set of challenges and we must continue to examine and monitor what is happening in this county.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

“Perhaps 10% of people in prison are innocent”

Perhaps they are all innocent or guilty. Perhaps you could stick to something more concrete.

In the one Yolo case you cite wasn’t Ornelas at the scene? Yes. Was he an innocent witness?No. Did he immediately make a statement implicating the person who accused him? No. Did his accuser go free? I don’t think so but can’t recall.

These things are always cloudy not crystal clear. If you expect perfection you are going to have a lot more crime. That will also have its costs.

The system is suppose to err on the side of innocence unless proven guilty.

Ornelas was at the scene, the question is whether he shot the gun at Abel Trevino. Mr. Trevino did not immediately implicate Ornelas, only after a lengthy discussion did he do so. On the stand, he couldn’t remember everything one day and the next day, he remembered every last detail. I was there, it was not believable.

Macobet cut a deal, he got four years for his involvement, Ornelas is getting 45. It was Macobet’s gun, his girlfriend, his feud, why is Ornelas then shooting at Trevino, he had no motive?

“If you expect perfection you are going to have a lot more crime. “

That’s a pretty incredible statement, as I understand it, you don’t care if innocent people are put in jail as long as crime is lower. Why not go to the more draconian and efficient means, someone commits a crime, shoot ten random people on the street. No one will dare commit a crime after awhile.

Mr. Toad: “If you expect perfection you are going to have a lot more crime. ”

dmg: “That’s a pretty incredible statement, as I understand it, you don’t care if innocent people are put in jail as long as crime is lower. Why not go to the more draconian and efficient means, someone commits a crime, shoot ten random people on the street. No one will dare commit a crime after awhile.”

If you expect/demand perfection from the legal system, you will NEVER convict criminals. And from much of your previous commentary, that is the impression you give your readers – there must be absolute perfection in a trial, else the jury should not convict. (Beyond a reasonable doubt is the required standard, not perfection.) However, perfection in a trial is never possible. Trials are messy for numerous reasons, bc life itself is messy. Life does not fit into nice neat little packages for convenience’s sake.

While I agree with your basic points about the problems with our legal system, I do not agree that perfection is a prerequisite to conviction.

Nevertheless, I do believe investigations of criminal activity should follow wherever the evidence leads. Evidence should not be cherrypicked to fit any preconceived agenda. That sort of unbiased investigation takes uncompromising integrity.

The burden of proof is beyond a reasonable doubt, that doesn’t mean perfection, it just means you have to eliminate doubts. There are plenty of times where that burden is met. For example, in the Arias case, there was no doubt he violated probation and strong evidence that he was in possession of a stolen weapon.

[i]”… the difference between whites and blacks receiving death sentences is far greater than the white versus black discrepancy in the overall criminal justice system.”[/i]

Any real evidence for this?

I did some research on the death penalty in California some years ago and discovered that whites accused of death-penalty eligible crimes in our state were [i]far more likely[/i] to be tried for death than non-whites. That is, where the prosecutor had discretion to seat a death-eligible jury, he was more likely to do so if the accused was white. (I can’t find the percentages in my notes. I just looked. But my recollection was the difference was large.)

Second, of those on death row in California, whites made up a higher percentage than they did of the total California population incarcerated for homicide.

Third, of those executed since the death penalty was reinstated in California–a tiny percentage of all murderers, of course–whites have thus far been executed at a higher percentage than non-whites relative to the rate at which whites have been convicted of homicide.

I imagine your statement about “blacks receiving death sentences” is from a national, not state perspective. Yet even there I suspect if you look at all blacks convicted of homicide and all whites convicted of homicide, the percentage of blacks from that population who are executed is [i]smaller[/i] than the percentage of whites.

There have also been studies of the death penalty which looked at the victim’s race. (I did not do that when I looked at the California numbers.) Those show that when the victim of a homicide is white, prosecutors are more likely to seek the death penalty. The result of this affects the white-black difference in being executed. Most homicides are intra-racial. Whites tend to be killed by whites; blacks by blacks. Insofar as the killers of whites are more likely to be tried for the death penalty, white killers are more likely to get the death sentence.

One other thing which needs to be kept in mind when comparing whites and blacks and the death penalty: blacks are 7 times as likely ([url]http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/homicide/race.cfm[/url])* to commit a homicide than a white is. A black is also 6 times as likely to be the victim of a homicide than a white. So if the percentage of all blacks getting the death penalty as a percentage of the total black population is higher than the percentages for whites, that is clearly explained by the great discrepancy in homicide rates.

*Note that black homicide rates have fallen almost in half in the last 35 years. Back in the mid 1970s, the black homicide rate was more than 10 times that of the white homicide rate.

[quote]I imagine your statement about “blacks receiving death sentences” is from a national, not state perspective. Yet even there I suspect if you look at all blacks convicted of homicide and all whites convicted of homicide, the percentage of blacks from that population who are executed is smaller than the percentage of whites. [/quote]

The numbers reported were controlled for proportions, in other words the numbers reflect the differential of the conviction rate.

The problem of course is whether the conviction rate really reflects the homicide rate differential or it is an artifact of the same flawed system.

The Baldus study simply looked at Georgia numbers, which are likely to be more skewed than in California. North Carolina has found a similar problem.

Rich: Here are some of the findings from the Baldus study, I think this addresses your concerns. A good methodologist is not going to get tripped on the issue that you raised.

[quote]D. Baldus, C. Pulaski, and G. Woodworth, Equal Justice and the Death Penalty (Boston: Northeastern University Press 1990).

A study of death sentences in the state of Georgia. Some results:

Defendants who kill W get CP in 11% of cases

Defendants who kill B get CP in 1% of cases

CP in 22% cases of B defendant, W victim

CP in 8% cases of W defendant and W victim

CP in 1% of cases of B defendant and B victim

CP in 3% of cases of W defendant and B victim

So black defendants who kill whites have greatest chance of getting CP.

Controlling for 39 nonracial variables (income class of defendant and victim, mode of killing, etc.), Baldus, et. al., found that the odds of being executed were 4.3 times greater for defendants who killed whites than for defendants who killed blacks.

Overall, 4% of black defendants received CP; 7% of white—chiefly because blacks are more likely to kill blacks than whites.

Again controlling for nonracial variables, the study found that other things equal (e.g. same race of victim, other variables the same), black defendants are 1.1 times likely to get CP as whites.

[/quote]

You talk about black and white, in Yolo with the present DA I am sure you would find the same thing between Mexican and whites, since the DA seems to love going after Hispanics under the ruse of “gang members or gang issues”.

As for Death Penalty, I have been a big supporter of this for my entire life, however after watching DA Jeff Reisig during the past few years and talking to many attorneys that work for him, I will never promote or vote for the Death Penalty again. It is far too easy for a DA to manipulate too many things for his own agenda. He can do false press releases (manipulate the press), he can hide evidence under the cover of immunity or say he did not “think” it was discoverable, he can influence police and investigations, he can put pressure on other elected leaders, he can politicize emotional crimes to help his agenda, he can put pressure on his Deputy DAs to get more convictions, he can make unethical plea deals just to get his agenda promoted, he can threaten anyone that goes against him with criminal investigation, he can cut back-room deals with promises of no or less charges to get people to say what he wants, he can misrepresent facts to the jury or hold information from them that hurts his case and many many more unethical tricks.

All of this makes the justice system too easy to corrupt or manipulate and this DA has really shown this extremely well.

No death penalty votes from me and no guilty verdicts from me, thanks to this “politically savvy” DA/Politician.

[i]”… in Yolo with the present DA I am sure you would find the same thing between Mexican and whites …”[/i]

I have not looked up the numbers on this for awhile, so my memory may be flawed, but I recollect that the overall crime rate for Hispanics in California is not that much higher than that for non-Hispanic whites. (This surprised me when I read it, because my perception was that our prison population was largely black and Hispanic.)

Asians have by far the lowest crime rate as a racial group. Blacks by far the highest. Hispanics and whites are in between, but both are closer to Asians than they are to blacks.

[i]”No death penalty votes from me and no guilty verdicts from me, thanks to this “politically savvy” DA/Politician.”[/i]

For all practical purposes–justice, retribution, fairness, revenge and crime prevention–we have not had the death penalty in California for 40 years. Other than the fortunes lawyers make defending and appealing death cases and the extra money paid to jailers, no one would much be affected if we got rid of the death statute. We have tens of thousands of murders for every one execution. The system is dysfunctional. It’s yet another sign that our system of government is broken.

[i]”CP in 22% cases of B defendant, W victim”[/i]

Keep in mind that these cases are highly unusual. Inter-racial murder is not the norm. I would also imagine that those cases tend to be tried by white prosecutors in mostly white communities. In a place like Georgia, the high number is not surprising.

[i]”CP in 1% of cases of B defendant and B victim”[/i]

I wonder if this 1% includes all cases which are tried or all cases of homicide? The difference could be high, if cases in which a black is killed by another black is much less likely to be solved. Nonetheless, these are the most common murders in the United States. I would also think that in a place like Georgia, the prosecutors and jurors are more likely to be black. As such, it may be their bias against the death penalty–if there is one–which reduces the chance of capital punishment.

[i]”CP in 8% cases of W defendant and W victim”[/i]

Again, most whites who are murdered are killed by another white (often a friend, neighbor or relative). In that these cases end up with the death penalty more often than black-black killings suggests maybe that white jurors (and prosecutors) tend to be more pro-death than black jurors.

[i]”CP in 3% of cases of W defendant and B victim”[/i]

The only comment I would add to this category is that because white-black murders are so uncommon and the death penalty itself is used so infrequently, I would guess this category might be suffering from a sample size problem.

Rich: I’d have to read the whole study, but a good methodological should be able to both recognize and take into account your concerns. The one point I think you make that might be a problem might concern the low number of white-black murders even in a universe of 2000 total cases. I’ll see what they come up with for the number of white-black murders.

dmg: “The burden of proof is beyond a reasonable doubt, that doesn’t mean perfection, it just means you have to eliminate doubts. There are plenty of times where that burden is met. For example, in the Arias case, there was no doubt he violated probation and strong evidence that he was in possession of a stolen weapon. That’s not perfection, it’s beyond a reasonable doubt. Reasonable doubt is generally considered 95% certainty not 100%. So the perfection argument is a strawman.”

Beyond a reasonable doubt does not mean the removal of all doubt. Nor is there any percentage put on the concept of beyond a reasonable doubt that I am aware of. Perfection is not a strawman if that is what you appear to be demanding…