On October 5, 2010, the Northern California Innocence Project came out with a report, “Preventable Error: A Report on Prosecutorial Misconduct in California 1997–2009,” that uncovered over 700 cases in which courts had found prosecutorial misconduct during an 11-year period. Of all of those cases, only six prosecutors were disciplined.

On October 5, 2010, the Northern California Innocence Project came out with a report, “Preventable Error: A Report on Prosecutorial Misconduct in California 1997–2009,” that uncovered over 700 cases in which courts had found prosecutorial misconduct during an 11-year period. Of all of those cases, only six prosecutors were disciplined.

The Vanguard has found four cases in Yolo County: Racimo, Lindeman, Massey, and Morales. However a source indicates a fifth case might be added, which would be the case of Lawrence James Miranda, which was overturned because the prosecutor, then-Deputy DA Jeff Reisig, withheld exculpatory evidence and the conviction was reversed on appeal.

The misconduct covered in the report ranged from failing to turn over evidence to presenting false evidence in court. As a response to their research, the Northern California Innocence Project is calling for legal reforms requiring courts to report all findings of misconduct to the state bar, which they currently are not required to do. When a court decides the misconduct was harmless, those cases often go unreported.

Shortly after the report was published, on October 18 the San Jose Mercury News reported that the State Bar would investigate 130 of these cases for possible disciplinary action.

Scott Thorpe, director of the California District Attorneys Association, faulted the study for exaggerating the problem of prosecutorial misconduct.

“It dramatically overstates the problem,” Mr. Thorpe told numerous media entities. “They didn’t quote one single prosecutor. It’s upsetting.”

Most observers are skeptical that the Bar would do anything with teeth, but it shows how seriously this has been taken.

Over two months later, it is still making news with CNN’s Anderson Cooper discussing the issue on his show just last week, devoting a whole hour to it.

The North California Innocence Project Study

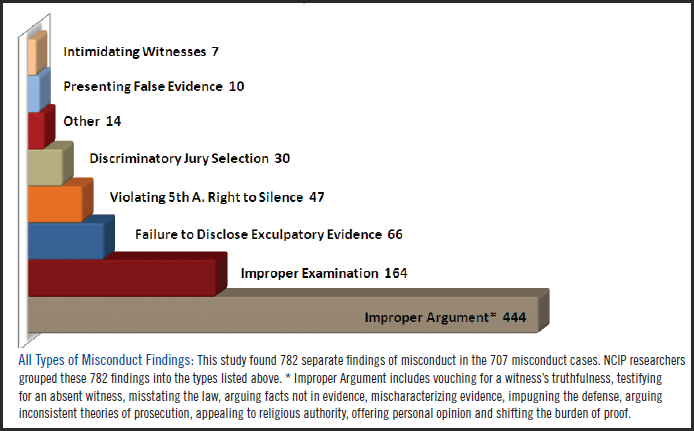

They write, “NCIP’s examination revealed 707 cases in which courts explicitly found that prosecutors committed misconduct. In about 3,000 of the 4,000 cases, the courts rejected the prosecutorial misconduct allegations, and in another 282, the courts did not decide whether prosecutors’ actions were improper, finding that the trials were nonetheless fair.”

While there are certainly critics of the study ranging from Mr. Thorpe quoted above to those who believe that the overwhelming number of cases reflect simple human mistakes that do not rise to the level of discipline for misconduct.

But for the first time, a study has documented these problems and there needs to be a mechanism by the State Bar or another entity to ensure that prosecutors, who possess a tremendous power over people’s lives, follow the rules that are set forward.

As the researchers write, “The Misconduct Study shows that those empowered to address the problem—California state and federal courts, prosecutors and the California State Bar—repeatedly fail to take meaningful action. Courts fail to report prosecutorial misconduct (despite having a statutory obligation to do so), prosecutors deny that it occurred, and the California State Bar almost never disciplines it.”

They go on to argue, “Significantly, of the 4,741 public disciplinary actions reported in the California State Bar Journal from January 1997 to September 2009, only 10 involved prosecutors, and only six of these were for conduct in the handling of a criminal case. That means that the State Bar publicly disciplined only one percent of the prosecutors in the 600 cases in which the courts found prosecutorial misconduct and NCIP researchers identified the prosecutor.”

And they add, “Further, some prosecutors have committed misconduct repeatedly. In the subset of the 707 cases in which NCIP was able to identify the prosecutor involved (600 cases), 67 prosecutors–11.2 percent—committed misconduct in more than one case. Three prosecutors committed misconduct in four cases, and two did so in five.”

This is not just about guilt or innocence. As they write, “Prosecutorial misconduct is an important issue for us as a society, regardless of the guilt or innocence of the criminal defendants involved in the individual cases.”

Instead they argue, “Prosecutorial misconduct fundamentally perverts the course of justice and costs taxpayers millions of dollars in protracted litigation. It undermines our trust in the reliability of the justice system and subverts the notion that we are a fair society.”

However, at its very worst it enables the guilty to go free and the innocent to be convicted. This is the part that people forget, putting an innocent person in prison or sentencing them to die does not merely harm an innocent, but it also prevents the real culprit from being found.

In their study, they distinguish between those cases in which the error was “harmful” – that is that something was done that was so fundamental that it altered the fairness of the case and forced the verdict to be set aside or the declaration of a mistrial.

However, even in cases where the errors were found to be harmless, the Innocence Project study argued that “harmless error cases may have involved infractions just as serious — and in some cases identical to” those in harmful error cases.

They argue further, “the egregiousness of a prosecutor’s misconduct does not determine the harmfulness of the error; the issue for harmless error review is whether despite the misconduct, the defendant received a fair trial. That means that very serious misconduct can be deemed harmless.”

They argued that appellate courts use a rather liberal application of the “harmless error” doctrine employed in the appellate review of misconduct.

They write, “Applying the harmless error doctrine, an appellate court may affirm a conviction even where prosecutorial misconduct or other errors occurred, if it believes that the error did not affect the outcome of the case. Only 20 percent of the prosecutorial misconduct cases were able to surmount this high hurdle. While this doctrine was originally intended to eliminate the need for multiple retrials for small technical mistakes, it has evolved to the point that it is now applied even to constitutional violations.”

In the second installment of this series, we will look more closely at five Yolo County Cases. One in particular, a murder case involving Deputy DA Robert Gorman. This case involving defendant Calixto Racimo actually was thrown out once because Mr. Gorman had misstated the law on aiding and abetting in his closing argument.

It went to trial again, and Mr. Gorman had failed to disclose exculpatory evidence in the two trials about an interview the Sheriff’s Department had done with a co-defendant. The appellate court allowed the decision to stand because the defense attorney, Yolo County Deputy Public Defender Richard Van Zandt, eventually received the discovery during the trial.

The problem that Mr. Van Zandt pointed out was there is a reason why we have the discovery process that we do. Had he received the discovery before the trial, the entire strategy may have been different. Discovering the evidence late precluded further investigation, further inquiry. This is technically a harmless error, except that in reality it was very harmful to the defendant’s case and the prosecutor was never disciplined and the appellate court allowed the conviction to stand.

The Innocence Project argues that even with those errors which are not deemed by the appellate court sufficiently egregious to sway the jury, the prosecutor should still be reported to the bar based on the severity of the conduct, rather than the guilt or innocence of the defendant.

Types of Misconduct

Failure To Disclose Exculpatory Evidence

They continue, “Brady violations are among the most pervasive forms of prosecutorial misconduct identified in the Misconduct Study. When prosecutors make the decision as to whether evidence is Brady material, their belief that the defendant is guilty can create a distorting prism through which they tend to view the evidence inaccurately as a red herring or irrelevant.”

Furthermore, the problem is the difficulty of knowing what one does not know.

The NCIP writes, “Brady violations are, by their nature, difficult to uncover; they become apparent only when the withheld material becomes known in other ways.”

“Brady violations are among the most pernicious forms of prosecutorial misconduct. Failure to disclose Brady material keeps the jury from considering proper and admissible evidence supporting the innocence of the defendant. Without access to this evidence, innocent defendants face a serious risk of being convicted for a crime they did not commit” the report continues.

The report cites Professor Bennett L. Gershman who they describe as one of the nation’s leading scholars on prosecutorial misconduct and Brady violations. He said, “[A] prosecutor’s violation of the obligation to disclose favorable evidence accounts for more miscarriages of justice than any other type of malpractice, but is rarely sanctioned by courts, and almost never by disciplinary bodies.”

The report says while it is impossible to know how many Brady violations have occurred, one study of all 5760 capital convictions in the US from 1973 to 1995 “found that the suppression of evidence by prosecutors was responsible for 16 percent of reversals at the state post-conviction stage. The Misconduct Study uncovered 66 cases where courts found prosecutors had committed Brady violations, including several that occurred in death penalty prosecutions.”

The Failure to Disclose Exculpatory Evidence is one of the charges actually most prevalent in Yolo County and it has been charged in several cases that are not cited in the Innocence Project report.

One example is the failure to turn over exculpatory evidence in the Halloween Homicide case, which led in part to three men being imprisoned for a crime they likely did not commit.

We learned of some of this through investigators Rick Gore and Randy Skaggs.

Rick Gore, in his March 2008 letter to DA Jeff Reisig, wrote, “One major disagreement you and I had was when you tried to hide and conceal discoverable evidence about a material witness and refused to discover evidence during an on-going murder trial.”

He continued, “Bruce Naliboff told me, in front of you, to “put a muzzle” on Randy Skaggs for talking about this discovery issue. You and I had extensive email discussion about this. Lt. Skaggs was in the office when Dave Henderson had to order you to comply with the law and therefore discover the evidence. I am sure the date of the gun test and the date of discovery of the report will show the long delay in providing this evidence, shooting and gun test, to the defense.”

In a follow up to the letter, Mr. Gore added, “Another shameful finding of the county is that Dave Henderson did in fact have to order Mr. Reisig to discover the gun flash test during the Halloween Homicide trial. Then the county made the finding that the test was not discovered because of my objections. In all my years, I have never had to go to the District Attorney because a Deputy DA was trying to withhold evidence from the court and the defense. The fact that this incident had to be elevated to the District Attorney, Dave Henderson, and he had to order Mr. Reisig to turn it over, is pretty good proof that this evidence was being concealed and was not going to be discovered without my objections.”

This charge is bolstered by those of Randy Skaggs, a ten-year-veteran DA Investigator who alleged that he was retaliated against for whistleblowing on the DA’s Office.

The lawsuit by Mr. Skaggs alleged that this discipline was retaliation for disclosure of exculpatory evidence. It says, “The Defendant[s] have initiated retaliatory and frivolous administrative proceedings and actions against the Plaintiff, because he brought to the attention of the DA OFFICE, including the District Attorney, exculpatory evidence relating to other criminal investigations and prosecutions, and that thereafter the DA was forced to turn over evidence to defense counsel.”

The Yolo Judicial Watch Project considers these findings extremely important. Critics have questioned how many of this DA’s cases have been thrown out. Unfortunately, the number of cases thrown out and reversed are few, but there is mounting evidence of misconduct. We will begin by looking at just four cases, but we believe that number to understate the nature of the problem by a large margin.

We strongly recommend people interested in this issue to watch the full Anderson Cooper 360 show on the subject of Prosecutorial Misconduct. Click here to watch that video.

The second part of the article later this week will look at the four official NCIP Yolo County cases, plus add material from the Miranda case as well as the Halloween Homicide Case.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

dmg: “On October 5, 2010, the Northern California Innocence Project came out with a report, “Preventable Error: A Report on Prosecutorial Misconduct in California 1997–2009,” that uncovered over 700 cases in which courts had found prosecutorial misconduct during an 11-year period. Of all of those cases, only six prosecutors were disciplined.”

700 cases out of how many cases tried, if you know?

dmg: “The report says while it is impossible to know how many Brady violations have occurred, one study of all 5760 capital convictions in the US from 1973 to 1995 “found that the suppression of evidence by prosecutors was responsible for 16 percent of reversals at the state post-conviction stage. The Misconduct Study uncovered 66 cases where courts found prosecutors had committed Brady violations, including several that occurred in death penalty prosecutions.””

In STRICKLER V. GREENE (98-5864) 527 U.S. 263 (1999) 149 F.3d 1170, affirmed:

“There are three essential components of a true Brady violation: the evidence at issue must be favorable to the accused, either because it is exculpatory, or because it is impeaching; that evidence must have been suppressed by the State, either willfully or inadvertently; and prejudice must have ensued.”

As you can see, whether something is exculpatory evidence can often be a very subjective call…

Also in article “The “Brady Dump”” in NY Law Journal, Sept. 4, 2009: “Thousands of prosecutors make Brady calls day in and day out as they try and win convictions, with a heavy layer of procedural insulation for any close calls. Indeed, only a handful of federal prosecutors are formally investigated and disciplined each year for failure to comply with Brady. This prosecutorial independence, coupled with the formidable standard that defendants face in proving that a suppressed piece of evidence would have undermined confidence in the verdict, my tempt less-than-fastidious prosecutors to not show all their cards. Bear in mind, too, that defense attorneys will not, typically be interested in seeking the discipline of prosecutors for Brady violations for a variety of reasons – not the least of which is potentially incurring the wrath of all, or even most, of the prosecutors in that office in the future.”

Funny you mention Dep DA Gorman, withhold and hiding statements and that is the same thing the DA Jeff Reisig was doing. According to many in the DA’s office, Jeff Reisig was the Best Man at Mr. Gorman’s wedding.

[quote]Birds of a feather – flock together[/quote]

You have to do things several times and really do it badly to get any problems from the bar, that are public. Of course, lots and probably most all disciple are kept “non-public”, so most will never know if or how many times an attorney was actually disciplined.

However, Dep Gorman has been disciplined more than once and even had his license suspended/removed to practice law, yet he was allowed to keep his job at the DA’s Office as a prosecutor, even during his suspension. See the state bar entry at the below link:

[url]http://members.calbar.ca.gov/search/member_detail.aspx?x=176092[/url]

This just confirms what many refuse to see. DA Jeff Reisig is unethical, cannot be trusted and the people closest to him reflect his ethics, yet like this story points out, why should he change or care?

“700 cases out of how many cases tried, if you know? “

No idea. But that is also only known cases and there are several that they missed in Yolo County.

RR: “You have to do things several times and really do it badly to get any problems from the bar, that are public. Of course, lots and probably most all disciple are kept “non-public”, so most will never know if or how many times an attorney was actually disciplined.”

All discipline of attorneys is made public.

RR: “However, Dep Gorman has been disciplined more than once and even had his license suspended/removed to practice law, yet he was allowed to keep his job at the DA’s Office as a prosecutor, even during his suspension. See the state bar entry at the below link:…”

So clearly attorney discipline is made public.

erm: “700 cases out of how many cases tried, if you know? ”

dmg: “No idea. But that is also only known cases and there are several that they missed in Yolo County.”

This is important context. If it is 700 cases out of 7,000, or 700 cases out of 70,000, it makes a difference – 10% vs 1%. However, if a person is innocent, it makes not a whit of difference…

There is a petition that speaks to the issues brought forth by the Santa Clara University’s report on prosecutorial misconduct. The petition states:

When the average person gets caught breaking the law, the California criminal justice system punishes them, often without mercy. But data shows that when California prosecutors break the law and engage in misconduct, they do so with impunity. Between 1997 and 2009, judges explicitly found prosecutors engaged in misconduct 707 times, with 67 prosecutors engaging in it more than once. Yet during that period, just six were disciplined by the California State Bar, according to data compiled by the Veritas Initiative at the Santa Clara University School of Law…

If you would like to sign the petition go to:

http://criminaljustice.change.org/petitions/view/end_immunity_for_prosecutorial_misconduct_in_california