The Veritas Initiative, the research and policy arm of the Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP) at Santa Clara University School of Law, today released Preventable Error: Prosecutorial Misconduct in California 2010, which follows up on last October’s Presentation.

The Veritas Initiative, the research and policy arm of the Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP) at Santa Clara University School of Law, today released Preventable Error: Prosecutorial Misconduct in California 2010, which follows up on last October’s Presentation.

While Yolo County did not have any reports of prosecutorial misconduct officially in 2010, the report adds the 2000 Miranda case that the Vanguard had noted previously.

The researchers found that in 102 cases, courts found that prosecutors committed misconduct. Courts would highlight 130 instances of misconduct within those case.

In 26 of the cases, the finding was serious enough to result in the setting aside of the conviction or sentence, declaring of mistrial or barring of evidence. Eighteen of those were reversals of convictions, with eight of those convictions being for murder.

In 76 of the cases, the courts nevertheless upheld the convictions, ruling that the misconduct did not alter the fundamental fairness of the trial.

In 31 other cases, the courts refrained from making rulings on the allegations of prosecutorial misconduct, instead holding that any error would not have undermined the fairness of the trial or that the issue was waived.

This report follows the publication in October 2010 by the Veritas Initiative of Preventable Error: A Report on Prosecutorial Misconduct in California 1997-2009, the most comprehensive, statewide review of prosecutorial misconduct ever done in the United States. That report included detailed findings of specific cases of prosecutorial misconduct in California, covered how the justice system identifies and addresses it, and made specific recommendations for reform. The report addressed its cost and consequences, including the wrongful conviction of innocent people.

That report found more than 700 instances of prosecutorial misconduct. After the publication of the report, the California State Bar began an investigation into more than 150 of the cases cited by the Veritas Initiative. That investigation is ongoing.

With the addition of the findings in 2010, the Veritas Initiative has identified more than 800 cases where courts found prosecutors committed misconduct.

These findings range from egregious misconduct, such as concealing evidence favorable to a defendant, to reckless or unintentional misconduct that in some was ameliorated at trial by judicial admonition or a special jury instruction.

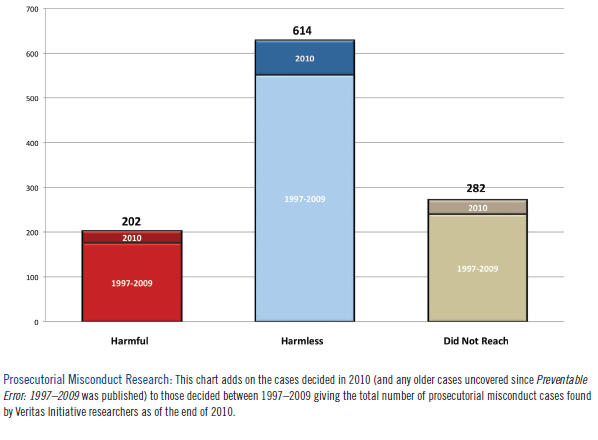

This is a summary of the total findings from 1997–2010:

• In more than 800 cases, courts found that prosecutors committed misconduct.

• In 202 cases, the finding resulted in setting aside of conviction or sentence, mistrial or barring of evidence.

• In 614 cases, the courts found that the misconduct did not affect the fairness of the trial.

• In 282 other cases, the courts did not make a finding of misconduct, instead holding any error would not have changed the outcome or the issue was waived.

• In the more than 800 cases of misconduct, 107 prosecutors were found to have committed misconduct more than once, two were cited for misconduct four times, two were cited five times and one prosecutor was cited for misconduct six times. Prosecutors who committed misconduct in multiple cases accounted for nearly one-third of all cases of misconduct.

“Our research shows that prosecutorial misconduct continues across the state in a broad range of prosecutions ranging from burglary to rape and murder,” said Maurice Possley, Visiting Research Fellow at NCIP who co-authored the report with Jessica Seargeant, an attorney and researcher for the Veritas Initiative.

“It is stunning that 107 prosecutors have been found to have committed misconduct more than once,” Mr. Possley said. “And these 107 prosecutors are responsible for about one out of every three cases where misconduct is found.”

“This shows that just a small number of the thousands of prosecutors in California are responsible for a significant number of cases of misconduct,” said Mr. Possley. “This small group of repeat offenders casts a pall over the majority of prosecutors who are ethical and do their jobs properly.”

Mr. Possley said, “We are encouraged by the actions of the California State Bar, which began an investigation of more than 150 of the cases cited in our study of findings of misconduct from 1997 through 2009. But we believe that more work remains to be done by the courts and prosecutors themselves not only to report these findings to the State Bar, but to prevent this misconduct from occurring at all.”

These numbers actually underestimate the problem.

To begin with, “The Veritas Initiative believes that the number of misconduct cases identified between 1997 and 2010 is an undercount. Trial level findings of misconduct that are not reflected in appellate court rulings cannot be reviewed without searching every case file in every courthouse in the state.”

In their report they find that “An estimated 700 to 1,000 drug prosecutions were dismissed or dropped because prosecutors in the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office failed to disclose damaging information about a police drug lab technician.”

Recall that at that time the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office was run by now-Attorney General Kamala Harris.

The report writes, “In May, Superior Court Judge Anne-Christine Massullo found that prosecutors violated the constitutional rights of a vast number of defendants by failing to tell defense attorneys about problems relating to the lab technician who was engaged in cocaine-skimming.”

It continues that ten prosecutors “at the highest levels of the District Attorney’s Office” knew about the problems, but the information was never disclosed to attorneys for defendants whose cases involved the technician’s work. The failure “to produce information actually in its possession regarding [the technician] and the crime lab is a violation of the defendants’ constitutional rights,” the judge declared.”

Finally, “The judge was highly critical of the District Attorney’s Office for failing to have in place procedures designed to obtain and produce information for defense attorneys. The San Francisco District Attorney’s Office has since instituted policies regarding evidence disclosure.”

The report also finds about 107 multiple offenders.

They write, “With about 99 percent of the prosecutors now identified, the Veritas Intiative has identified the names of 677 prosecutors. Research shows that 107 were found to have committed misconduct more than once. The 107 prosecutors were cited in 251 cases. This means that a relatively small number of prosecutors were responsible for about one-third of all of the cases of misconduct.”

Miranda Revisited

As we reported back in December, a jury found defendant Lawrence James Miranda guilty of threatening to commit a crime which would result in death or great bodily injury and found he personally used a firearm in the commission of that offense.

According to the appellate court, “The victim saw the grip of the object outside defendant’s pants pocket and saw the shape of a barrel under the fabric of the pants pocket as defendant pointed the object toward her. From its appearance, and defendant’s threat to shoot her, the victim believed the object was a gun. However, when defendant and the other suspects were searched approximately two hours later, no gun was found. Nor was any gun found in the hotel room where the suspects were discovered. Likewise, a search of the area around the hotel revealed no gun. Officers also searched a barn several miles away, based upon Corrina Guavara’s statement that she had driven there with defendant, Carillo, and Avila after the three men had left Judy’s Bar. No gun was found in the barn. According to Officer Puffer’s testimony, the red car belonging to one of the suspects was found but, ‘to [Puffer’s] knowledge, it was never searched.’ ”

During summation, the prosecutor, Jeff Reisig, then Deputy District Attorney, argued that the officers’ failure to find a gun did not help defendant: “(T)hat’s not decisive of the charges here, because we have a witness (Leslie) who saw (a gun), (and defendant and the others) had two hours to dispose of evidence. ”

The key point here is, “Twice during deliberations, the jury sent notes to the court concerning the question of whether the object in defendant’s pants pocket was a firearm.”

After the verdicts were recorded and the jury was discharged, the prosecutor spoke with jurors outside the courtroom. The prosecutor and defense counsel had differing accounts of what happened next.

In the words of the prosecutor, Jeff Reisig: “While I spoke with the jury, (defense counsel) exited the courtroom and approached. As he approached, one of the jurors asked me if the red car had ever been searched. I responded that ‘I believed’ it had been searched by another police officer. My response was based on my assumption that with the number of police officers at the scene it would have been highly unlikely that no one searched the car. (Defense counsel) arrived at my location just as I made the above statement.”

Defense counsel Lawrence Cobb, of course, described it differently: “I left the courtroom to speak with the jury members who had remained. (The prosecutor) was already there speaking with some of the members of the jury, and from the content of the discussion it was apparent that he had been so engaged for some time.”

He continued, “I began speaking with (jurors) as well. asking questions about what was and what was not convincing evidence in their minds. While so speaking with the jury members, (the prosecutor) turned to me, and in a causal [sic] manner, told me, in substance, that he had received information that the car had been searched but no gun was found and that, apparently, Officer Puffer, was not aware that such a search of the car had been conducted. No other information was given to me nor did (the prosecutor) tell me when or how he had learned of such information.”

Believing that the prosecutor had withheld exculpatory evidence, defense counsel made “an Informal Request for Discovery,” and received two supplemental reports, each of which stated that Officer Scoggins searched Avila’s car after the suspects were detained, and found no gun in the vehicle.

Based upon this new information, defense counsel moved for a new trial on the grounds of newly-discovered evidence and prosecutorial misconduct (withholding exculpatory evidence) which had a bearing on the finding that defendant used a firearm while violating Penal Code section 422.

Defense counsel argued: “[T]he fact that the car had been searched and no weapon found was highly exculpatory and, coupled with the testimony of (the victim) regarding the alleged gun, as well as the testimony of (the DJ and bar owner) that they never saw a gun, it is reasonably probable that the jury would have found doubt and brought in a not true finding on the enhancement.”

The trial court denied the motion, stating: “I do not find that there is any probability that the jury would have come to a different result regarding the firearm enhancement, even if this additional information had been presented.”

However, the appellate court disagreed.

They wrote, “Without doubt, the presence or absence of a gun in defendant’s possession following the threat was material to the question whether the object in his pocket was a gun or whether he just simulated one. The evidence showed that, when defendant and his two companions were detained two hours later, searches revealed there was no gun on their persons, in the hotel room where they were found, in the area surrounding the hotel, or in a barn where they went after defendant had threatened the victim. This left three possibilities: the gun was left in the car; the gun was disposed of elsewhere; or there was no actual gun.”

They continued, “Certainly, jurors could infer Officer Puffer would have known about it if the car had been searched. Thus, Puffer’s testimony that, to his knowledge, the suspect vehicle was ‘never searched’ tended to provide one reason for the void: the missing gun was left in the car. We find it quite conceivable that the jurors may have been influenced by this implication.”

Furthermore, “If the jurors were told during the trial that the suspect vehicle had been searched and no gun was found, this would have eliminated a convenient and logical explanation for the absence of a gun.”

They wrote, “Hence, our confidence in the verdict on the use enhancement is undermined by the prosecution’s failure to disclose this material exculpatory evidence to the defense.”

They ruled, “The prosecutor violated defendant’s right to due process by failing to disclose to the defense the existence of material exculpatory evidence pertaining to the issue of whether defendant used a firearm while threatening to shoot the victim. Accordingly, the trial court erred in refusing to grant defendant’s motion for a new trial on that issue, and the use of a firearm enhancement must be reversed.”

The story was captured in a 2006 Davis Enterprise article.

Wrote the Enterprise, “The jury convicted the defendant, and while speaking with the jury afterward, Cobb said he overheard Reisig tell jurors there was a vehicle search during which no gun was found. Cobb says he believes Reisig knew that information, potentially favorable toward his client, before the jury received the case.”

According to the Enterprise, Mr. Reisig disputes Cobb’s version of events, calling it “outrageous.” They wrote, “He said the jury never received information about a vehicle search, though a police officer mentioned while the jury was deliberating the case that police had searched a car and the area around it, but found no weapon.”

The story continued, “The appellate court ruling, Reisig said, reflected the court’s opinion that the jury was entitled to hear information about the car search in case it would have affected the verdict. He added that there was no finding of intentional misconduct or hiding of evidence, and he declined to refile the gun charge because the defendant was performing well on probation.”

“It wasn’t the best use of resources to proceed with a new trial for the use of the gun,” Jeff Reisig told the Enterprise during the heat of the 2006 District Attorney race against his colleague Pat Lenzi.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

dmg: “The researchers found that in 102 cases, courts found that prosecutors committed misconduct. Courts would highlight 130 instances of misconduct within those case.”

102 cases of misconduct out of how many cases altogether? That important statistic was ommitted…why?

dmg: “They write, “With about 99 percent of the prosecutors now identified, the Veritas Intiative has identified the names of 677 prosecutors. Research shows that 107 were found to have committed misconduct more than once. The 107 prosecutors were cited in 251 cases. This means that a relatively small number of prosecutors were responsible for about one-third of all of the cases of misconduct.””

And how many of the serial offenders (prosecutors committing more than one instance of misconduct) are ELECTED officials?

Elaine- i dont find that stastic that important. It is hard to know the true universe of cases. In part there are universes of cases where possible misconduct occurred that will never get to the appellate stage. cases with acquittals or plea agreements. We may never know the universe but i do agree the number you see is low for pms.

To dmg: I guess my point is that if 99% of prosecutors seem to be following the law and doing their jobs correctly for the most part, that is a pretty good track record. Of course I recognize that figure may be misleading, bc not enough investigation may have been done into malfeasance in office. What I would say, though, is any prosector who has repeated violations should be looked at carefully, and appropriate action taken. What bothers me is those w repeated violations may be continue to be re-elected by the people who are more concerned w DAs being tough on crime than in justice. This should be a state bar/state attorney general issue if a DA has been caught 6 times for repeated misconduct…

Elaine:

It’s a difficult number to figure out, but if there were 100-some odd cases of known misconduct, I would guess, that’s a fraction of total cases. I count 22 counties with pm’s in 2010, that is out of what 58 counties, so about 40% of prosecutors.

I agree with a lot of the rest you say.

DMG,

“I count 22 counties with pm’s in 2010, that is out of what 58 counties, so about 40% of prosecutors.”

40% percent of all prosecutors or 40% of all CA counties had at least one prosecutor who has committed pm in 2010?

I guess the most accurate statement would be 40% of all prosecutors offices. I consider the DA as the prosecutor, but others may consider each deputy a prosecutor as well.