While it is a decision that only applies to the State of New Jersey, observers and analysts expect a decision rendered by the New Jersey Supreme Court earlier this week to have considerable impact nationally, as the U.S. Supreme Court will in November also return to the issue of eyewitness testimony, last considered in 1977.

The new changes, designed to reduce the likelihood of wrongful convictions by taking into account more than 30 years of scientific research on eyewitness identification and memory, require courts to greatly expand the factors that courts and juries should consider in assessing the risk of misidentification.

Barry Scheck, Co-Director of the Innocence Project, called the ruling, “a landmark decision.”

“Today the New Jersey Supreme Court has said that the legal architecture set by the U.S. Supreme Court 30 years ago to evaluate identification evidence must be renovated. This is a decision that will ultimately affect every state and federal court in the nation,” said Barry Scheck.

He continued, “The court has recognized the tremendous fallibility of eyewitness identifications, and based on the most thorough review of scientific research undertaken by a court, has set up comprehensive and practical guidelines for how judges and juries should handle this important evidence.”

The court’s decision requires judges to more thoroughly scrutinize the police identification procedures and many other variables that affect eyewitness identification. The court noted that this more extensive scrutiny will require enhanced jury instructions on factors that increase the risk of misidentification.

In the case at hand, the defendant argued that an eyewitness mistakenly identified him as an accomplice to a murder. He would argue that this identification was unreliable due to the fact that officers investigating the case intervened during the identification process and unduly influenced the eyewitness.

The court noted, referring to scientific studies conducted on the subject,”Study after study revealed a troubling lack of reliability in eyewitness identifications.”

Chief Justice Stuart J. Rabner, in the unanimous decision, continued, “”From social science research to the review of actual police lineups, from laboratory experiments to DNA exonerations, the record proves that the possibility of mistaken identification is real.”

“Indeed, it is now widely known that eyewitness misidentification is the leading cause of wrongful convictions across the country.”

The court concluded, “That evidence offers convincing proof that the current test for evaluating the trustworthiness of eyewitness identifications should be revised.”

The court continued, “We are convinced from the scientific evidence in the record that memory is malleable, and that an array of variables can affect and dilute memory and lead to misidentifications. Those factors include system variables like lineup procedures, which are within the control of the criminal justice system, and estimator variables like lighting conditions or the presence of a weapon, over which the legal system has no control.”

They add, “In the end, we conclude that the current standard for assessing eyewitness identification evidence does not fully meet its goals. It does not offer an adequate measure for reliability or sufficiently deter inappropriate police conduct.”

A crucial point is made here: “It also overstates the jury’s inherent ability to evaluate evidence offered by eyewitnesses who honestly believe their testimony is accurate.”

Clearly, that could be extended to a number of other areas as well – most particularly the evaluation of recorded confessions.

The court said that whenever a defendant presents evidence that a witness’s identification of a suspect was influenced, by the police for instance, a judge must hold a hearing to consider a broad range of issues. These could include police behavior, but also factors like lighting, the time that had elapsed since the crime or whether the victim felt stress at the time of the identification.

The judge would then be required, when disputed evidence is admitted, to provide detailed explanations on influences that could be seen to heighten the risk of misidentification.

The court came up with a number of parameters that should be included in scrutinizing police identification procedures:

These factors (as summarized in the Innocence Project’s press release) include:

- Whether the lineup procedure was administered “double blind,” meaning that the officer who administers the lineup is unaware who the suspect is and the witness is told that the officer doesn’t know.

- Whether the witness was told that the suspect may not be in the lineup and that they need not make a choice.

- Whether the police avoided providing the witness with feedback that would cause the witness to believe he or she selected the correct suspect. Similarly, whether the police recorded the witnesses’ level of confidence at the time of the identification.

- Whether the witness had multiple opportunities to view the same person, which would make it more likely for the witness to choose this person as the suspect.

- Whether the witness was under a high level of stress.

- Whether a weapon was used, especially if the crime was of short duration.

- How much time the witness had to observe the event.

- How far the witness was from the perpetrator and what the lighting conditions were.

- Whether the witness possessed characteristics that would make it harder to make an identification, such as age of the witness and influence of alcohol or drugs.

- Whether the perpetrator possessed characteristics that would make it harder to make an identification. Was he or she wearing a disguise? Did the suspect have different facial features at the time of the identification?

- The length of time between the crime and identification.

- Whether the case involved cross-racial identification.

The court also cited findings by Brandon Garrett, a law professor at the University of Virginia, who documented in a recent book, “Convicting the Innocent,” eyewitness misidentifications in 190 of the first 250 cases of DNA exonerations in the country.

“In half of the cases, eyewitness testimony was not corroborated by confessions, forensic science or informants,” the court wrote. Moreover, “Thirty-six percent of the defendants convicted were misidentified by more than one eyewitness.”

They continued, “As we recognized four years ago, “[i]t has been estimated that approximately 7,500 of every 1.5 million annual convictions for serious offenses may be based on misidentifications.”

The New York Times reported two days earlier that “the Supreme Court will return to the question of what the Constitution has to say about the use of eyewitness evidence. The last time the court took a hard look at the question was in 1977. Since then, the scientific understanding of human memory has been transformed.”

The American Psychological Association submitted a brief, arguing, “Research shows that juries tend to ‘over believe’ eyewitness testimony.”

“It is exciting that the court has actually taken an eyewitness ID case for the first time in many years,” Professor Garrett told the New York Times, “even if it might be the wrong case on the wrong issue.”

The New Jersey court gave the Criminal Practice Committee and the Committee on Model Criminal Jury Charges 90 days to submit proposed revisions to the current jury instructions on eyewitness identification, specifically directing them to consider the model jury instructions submitted by the Innocence Project.

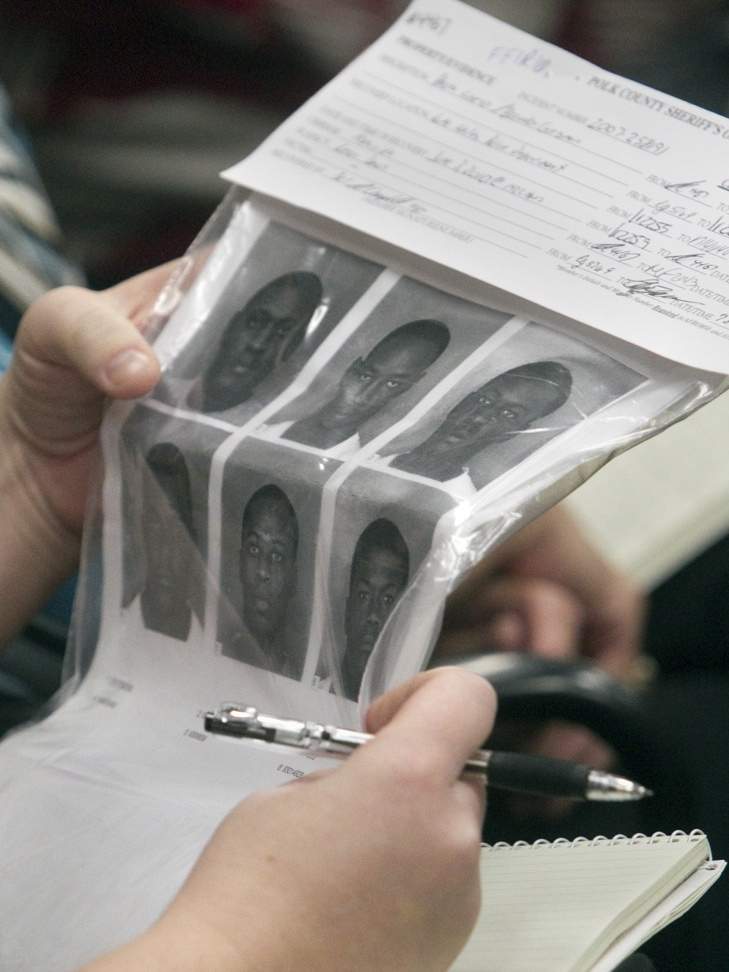

According to the release from the Innocence Project, the court’s decision stems from the 2004 conviction of Larry Henderson, a Camden man who received an 11-year prison sentence for reckless manslaughter and weapons possession related to a fatal shooting in January 2003.

He appealed the photo lineup procedure because officers failed to follow the New Jersey Attorney General’s Guidelines, issued in 2001, for conducting identification procedures. The appeals court agreed and ordered a new hearing on the admissibility of the photographic identification of Henderson.

Before that could occur, the state appealed, and the New Jersey Supreme Court decided that an extensive inquiry into witness identification procedures currently used by law enforcement was necessary.

According to the Innocence Project release, “The New Jersey Supreme Court appointed a Special Master to review the legal standard for the admissibility of eyewitness testimony known as the ‘Manson test,’ established by the United States Supreme Court in 1977 and fully embraced by 48 out of 50 states, including New Jersey in 1988 in State v. Madison.”

In addition to the parties to the litigation, the court invited the Innocence Project and the Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers of New Jersey to participate in the inquiry by the Special Master, who considered over 200 scientific studies and heard from some of the nation’s most respected experts on eyewitness identification before issuing findings to the court in June 2010.

In accordance with the decision, the court remanded the Henderson case back to the trial court for further review.

The Innocence Project states, “The decision will apply to all future cases, but will not be applied retroactively, with the exception of the companion case, State v. Chen, in which the court held that suggestive identification procedures that resulted from private actors would also be subject to court scrutiny to ensure the reliability of the identification.”

—David M. Greenwald reporting

[quote]In accordance with the decision, the court remanded the Henderson case back to the trial court for further review.[/quote]

In other words Henderson is not necessarily innocent. Only time will tell on his retrial, but I assume there will be changes in regard to the admissibility of the eyewitness testimony. You never really say what the problem was about the eyewitness testimony. What was done wrong, if you know…

My son was involved in a photo lineup, and had to identify his assaulter. The police officer brought a group of six photos, made no move to influence my son one way or the other, and my son had no trouble identifying his attacker from the photos.

In another case I know about from Washington, D.C., a rape victim positively identified her attacker as a young engineer who was married with kids, and who also had been at work the day of her attack. Even though some 30 witnesses were brought into court to testify the defendant was at work when the crime was committed and could not have been guilty of the crime alleged, he was convicted and sentenced to a long term in the state penitentiary. He was freed about two years later when they found the real perpetrator. The odd thing was the two looked like twins – down to the exact same goatee and hairstyle. It was uncanny.

Closer to home, I remember the cold case of the two UCD college sweethearts that were murdered right here in Davis. The prosecution tried to allow evidence of an eyewitness that she saw so-and-so drive by in the dark of night and saw the defendant through the window of a van driving by, 12 years prior, and somehow remembered it was in fact the defendant and no one else. She was positive. The judge threw the testimony out as completely unreliable/implausible.

[quote][i]”A crucial point is made here: ‘It also overstates the jury’s inherent ability to evaluate evidence offered by eyewitnesses who honestly believe their testimony is accurate’.

Clearly, that could be extended to a number of other areas as well – most particularly the evaluation of recorded confessions.”[/i][/quote]This is such a leap. The differences between eyewitness reports and recorded confessions are manifest.

In one case, the witness is reporting on what he thinks he saw, a notoriously unreliable process. In the other case the confessor is reporting what he did–who should know better?

Why is it clear to you that a jury’s abilities to evaluate a confession are hampered in the way the court describes (by defendant’s knowledge that his statement is accurate)?

By the time his confession gets to trial, the defense attorney usually is claiming he didn’t mean what he said in the recording, and the jury has been put on notice not to accept it as accurate.

Jury “over-belief” is a real threat since witnesses would be as convinced of their mistaken identifications as accurate ones. Sorting out whether a defendant is telling the truth now or in a conflicting confession doesn’t threaten a trial’s fairness in the same way.

[quote][i]”The prosecution tried to allow evidence of an eyewitness that she saw so-and-so drive by in the dark of night and saw the defendant through the window of a van driving by, 12 years prior, and somehow remembered it was in fact the defendant and no one else.”[/i][/quote]Makes me realize that the defense often relies on eyewitness accounts that could be just as inaccurate. But it’s not as serious a problem for the trial process.

[quote]…the Supreme Court will return to the question of what the Constitution has to say about the use of eyewitness evidence. The last time the court took a hard look at the question was in 1977. Since then, the scientific understanding of human memory has been transformed.”[/quote]

OK, using that logic we should also expectt the SCOTUS to address the issue of abortion too.

AdRemmer

I am not understanding. can you elaborate on how you think these two topics are related ?

All I know is what I see on my TV. In the show The First 48, just about every metropolitan homicide investigative team uses a 3 over 3 six-shot photo line-up. About 80% to 90% of the time the witness picks out the person the cops are hoping they will pick out. The other 10% to 20% of the time, they usually say, “I’m not sure.” I can only recall one case where the witness was certain, “That’s the one!,” when the cops knew the guy picked out was just some random dude from the system.

In the cases I have seen, it is never true that an eyewitness picking out the right picture ends the case. What it usually does is two things: it points the investigators in the direction of their prime suspect, allowing them to collect other evidence on him (perhaps including getting a search warrant to find if his shoes match a shoe print or if he has possession of the gun which matches the ballistics or if he has clothing which has forensic evidence or matches the description given by witnesses, etc.); and it lets the cops bring in the suspect, who, if guilty, will 6 out of 10 times confess to the crime or part of the crime, 3 times in 10 “lawyer-up” and 1 time in 10 insist on his innocence.

As to those who insist they are innocent, it seems to me most experienced investigators get a good read on the suspect pretty fast: they recognize when someone is really innocent* and professing that; or they recognize that when someone is lying to them, he will tell a whole series of lies in professing his innocence which, of course, makes the cops more convinced he is guilty.

*Cases are never solved based on a read, of course. But that is a skill that all the good investigators I have seen on TV seem to have.

One final note: Before I started watching The First 48, I had much less appreciation for the interrogative skills that many female cops seem to have. The best of these is a woman who works homicides in Memphis, TN, named Caroline Mason. She has a knack to get murderers to confess. Males interrogators are almost never as good as she is.

[img]http://msjacks.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/caroline-mason.jpg[/img]

“In one case, the witness is reporting on what he thinks he saw, a notoriously unreliable process. In the other case the confessor is reporting what he did–who should know better? “

And yet look at the research on wrongful convictions and the large number that are based on faulty confession.

Have you read this NY Times article ([url]http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/14/us/14confess.html?_r=4[/url])? Still think it’s a stretch?

“Why is it clear to you that a jury’s abilities to evaluate a confession are hampered in the way the court describes (by defendant’s knowledge that his statement is accurate)? “

Because here is what an expert said:

[quote]Professor Garrett said he was surprised by the complexity of the confessions he studied. “I expected, and think people intuitively think, that a false confession would look flimsy,” like someone saying simply, “I did it,” he said.

Instead, he said, “almost all of these confessions looked uncannily reliable,” rich in telling detail that almost inevitably had to come from the police. “I had known that in a couple of these cases, contamination could have occurred,” he said, using a term in police circles for introducing facts into the interrogation process. “I didn’t expect to see that almost all of them had been contaminated.”[/quote]

So you have an expert who has trouble discerning it. And he is looking at cases where DNA has ruled it out.

“In other words Henderson is not necessarily innocent. “

You do understand how the appellate process works right? The appellate does not decide guilt or innocence, they decide if the error at the lower level is sufficient to have a new trial. If they rule that the error was sufficient they remand the case to lower court. The prosecution would then evaluate the extent to which throwing out the witness id would impair their case. Because this just happened, my guess would be that no one has looked at it yet. Based on the description of the case, you can kind of guess what will happen, but because this just happened we don’t know for sure.

[quote]You do understand how the appellate process works right?[/quote]

Yes, I am well aware how the appellate process works. And my point still stands – Henderson is not necessarily innocent. Again, do you know what the problem with the eyewitness testimony was?

[i]”And yet look at the research on wrongful convictions and the [b]large number[/b] that are based on faulty confession.”[/i]

This is not true, David. It’s not a large number. It’s a very small percentage of the time the person confesses that he is actually innocent. Most of those very small number of times the confessor is mentally ill. And that points to the larger problem: our unwillingness to force the mentally ill into psychiatric care BEFORE they commit crimes.

[i]”Have you read this NY Times article?”[/i]

It says there have been “more than 40” cases in the last 35 years:

[i]”But more than 40 others have given confessions since 1976 that DNA evidence later showed were false, according to records compiled by Brandon L. Garrett, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law.”[/i]

Let’s say it is 5 times that many, or 200 cases. There are probably 200 or more correct confessions to felonies* every day in the United States. That means over the last 35 years, if 200 have falsely confessed, we are not talking about 1 percent, or 1/10th of 1 percent, we are talking about 1/100th of 1 percent.

So the last thing you want to take away from law enforcement is the ability to wring out a confession.

That said, the NYT piece correctly advises that all interrogations of prime suspects should be videotaped, so if there is a confession, the court can decide if it was fairly drawn.

*I read recently that there are about 50 murders a day in the United States.

A study of the studies of false confessions by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers ([url]http://www.nacdl.org/public.nsf/0/4a6e9aa597092057052573ed0056ffa3?OpenDocument[/url]) claims that from the early 1960s to 2007 (when their study was published) there were 250 cases of false confession:

[i]”Collectively these studies alone document more than 250 interrogation-induced false confessions – the majority of which have occurred within the last two decades – and corroborate much of what we already know from dozens of case studies.”[/i]

Even if the number is twice that, it’s still a tiny percentage of all confessions.

Rich:

“This is not true, David. It’s not a large number. It’s a very small percentage of the time the person confesses that he is actually innocent.”

You misread my comment. My comment was not that a large percentage of time that a person confesses he is innocent, it’s a large number of wrongful convictions are based in part on a false confession.

Elaine:

I don’t know that much about the specifics of this particular case, and frankly I don’t really care that much. I’m much more concerned about the global ramifications of the ruling and fixing this process.

It does appear that, the eye witness testimony was the primary evidence:

“Wednesday’s New Jersey Supreme Court opinion, State v. Larry R. Henderson, stemmed from a case in which an eye-witness testimony was the primary evidence in a homicide trial. Before the trial, the witness said a detective was “nudging” him to identify the defendant.

The trial court admitted the eye witness’s identification, and while Henderson was acquitted of the most serious murder charges, he was convicted of reckless manslaughter, aggravated assault and weapons possessions charges. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison.”

So I don’t know if the guy is innocent, but unless there is other evidence tying him to the crime, it seems the charges will get dropped.

David, you argue that the cited case “clearly…could be extended to a number of other areas as well…(false confessions)” The reasoning for the decision appears to be that the “performance” given by a someone who really, really believes what he’s saying is way too convincing to a jury (esp. when the witness is testifying on something about which he doesn’t have a clue).

As you note, the research on this seems devastating. That we would put people in prison, or to death, based solely on such believable (yet wrong) testimony is a blot on our justice system history.

Insisting on corroborating evidence is an important step to correcting this injustice. Better instructions and other changes, as this decision requires in New Jersey, ought to be the law everywhere.

However, the logic that drives this decision (the unfair influence on a jury of an “eye witness” who didn’t see what he [u]is sure[/u] he saw) wouldn’t apply to the many recorded confessions that end up contested in court (even for the tiny percentage that are proven false). [quote][i]”Indeed, it is now widely known that eyewitness misidentification is the leading cause of wrongful convictions across the country.” [/i][/quote]There is no body of research suggesting a wrongful conviction problem of similar magnitude.[quote][i][u]JS[/u]–“In one case, the witness is reporting on what he thinks he saw, a notoriously unreliable process. In the other case the confessor is reporting what he did–who should know better?”

[u]David[/u]–And yet look at the research on wrongful convictions and the large number that are based on faulty confession.”[/i][/quote]Yes, I reread the [u]NYT[/u] article every time you suggest it. I think it still deals with a tiny number of bad convictions, ones that relied on faulty confessions. This isn’t to say this type of miscarriage isn’t worthy of fixing, just that the current eyewitness case won’t drive any solution. What is your suggestion for correcting bad confessions?

JS:

Innocence Project cites this statistic on false confessions: “In about 25% of DNA exoneration cases, innocent defendants made incriminating statements, delivered outright confessions or pled guilty.”

“However, the logic that drives this decision (the unfair influence on a jury of an “eye witness” who didn’t see what he is sure he saw) wouldn’t apply to the many recorded confessions that end up contested in court (even for the tiny percentage that are proven false).”

You are correct on this point, but I think your point is too limited. The problem that I see is that the jury has little ability to evaluate false confessions. Even an expert had trouble discerning false confessions from true ones. How is a jury going to be able to do that.

“What is your suggestion for correcting bad confessions? “

The IP has a list of remedies that includes videotaping them, but the problem is how is a layman individual going be able to appropriately evaluate videotaped confessions when an expert believes they look real.

You could have an expert evaluate the confession, but that costs money that most indigent defense attorneys lack.

Part of what I think this all gets at is the need to understand that any conviction which is based primarily on a single strand of evidence whether it is eyewitness identification or a confession ought to be scene as suspect. You need additional evidence. And yet talk to the jurors and a confession is often the most important piece of evidence, a juror in the Moses case believed that no one would confess to having raped their daughter who hadn’t – but it’s happened.

So one option is videotaping, jury instructions, but I think more stringent requirements during the interviews themselves. They are often done in a way to break the person down, tire them after hours of interrogation, etc.

I’m struck by the fact that the police to interrogate their own are required to give them a whole array of legal options that they do not give the lay person. The lay person who does not know if they are free to go and doesn’t think to ask for an attorney.

…the Supreme Court will return to the question of what the Constitution has to say about the use of eyewitness evidence. The last time the court took a hard look at the question was in 1977. Since then, the scientific understanding of human memory has been transformed.”

OK, using that logic we should also expectt the SCOTUS to address the issue of abortion too.

medwoman

[quote]I am not understanding. can you elaborate on how you think these two topics are related ? [/quote]

Stated simply re: abortion – my point is that the science available has “transformed.”

Similarly, we ought to also expect the SCOTUS “take a hard look” the more older abortion question.

AdRemmer

Given the sharp turn the SCOTUS has taken towards the originalist interpretation of the constitution as construed by Justices Thomas and Scalia, I cannot see how the transformation of scientific knowledge about abortion will in any way alter their views. So unless you are of the view that medical decisions should be governed by the religious and scientific views of the founding fathers based on the information available to them, it would probably be preferable not to review this issue.

MW – maybe it’s the jurists on the other side of the aisle who could possibly see things differently, in light of advanced technology and science?

[quote][i]”Part of what I think this all gets at is the need to understand that any conviction which is based primarily on a single strand of evidence whether it is eyewitness identification or a confession ought to be scene as suspect. You need additional evidence.”[/i][/quote]We certainly agree on this, but I’d guess that getting to “guilty beyond reasonable doubt” is easier for me than for you.

Each strand of evidence has different weight, varying on what other corroborating strands contribute. A recorded confession naturally rates high, even higher when supported by evidence found in a resulting search for example. [quote][i]”…a juror in the Moses case believed that no one would confess to having raped their daughter who hadn’t – but it’s happened.” [/i][/quote] But, that doesn’t mean that Moses was innocent. Or much of anything for that matter. You can’t give much weight to the [u][i]possibility[/i][/u] of something when [i][u]probability[/u][/i] is in play.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This might be a link to your 25% citation, a very interesting paper on false confessions:[quote]”Kassin and the paper’s other authors reach a clear conclusion: recording interrogations prevents false confessions.” [url]http://apublicdefender.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/kassin-fruit-false-confession.pdf[/url][/quote]