Edward Carter was a 19-year-old African-American man. He was convicted of the rape of a pregnant woman in Detroit in 1974 and sentenced to life in prison. That conviction, researchers Samuel Gross and Michael Shafer say, was based entirely on the cross-racial identification by the white victim.

Edward Carter was a 19-year-old African-American man. He was convicted of the rape of a pregnant woman in Detroit in 1974 and sentenced to life in prison. That conviction, researchers Samuel Gross and Michael Shafer say, was based entirely on the cross-racial identification by the white victim.

But Mr. Carter was one of the more fortunate people to have been wrongly convicted, because there was DNA evidence in this case that would exonerate him.

“Approximately 30 years later, he sought DNA testing through a Michigan innocence project. A search revealed that the biological evidence that was collected at the time of the crime had been destroyed, but a police officer who was involved in the search became curious,” they report.

That police officer would find fingerprints lifted from the crime scene, and they were eventually sent through the FBI’s Automated Fingerprint Identification system and matched to a convicted sex offender who was in prison for similar rapes committed at about that time in the same area.

Based on this new evidence, Mr. Carter was released in 2010 after serving more than 35 years in prison for a crime he did not commit.

Those who read this site, and others like it, know this is not an isolated incident.

As Professors Gross and Shafer write, “The tragedies are not limited to the exonerated defendants themselves, or to their families and friends. In most cases they were convicted of vicious crimes in which other innocent victims were killed or brutalized. Many of the victims who survived were traumatized all over again, years later, when they learned that the criminal who had attacked them had not been caught and punished after all, and that they themselves may have played a role in condemning an innocent person. In many cases, the real criminals went on to rape or kill other victims, while the innocent defendants remained in prison.”

Those who defend the current justice system and the relatively low frequency of false convictions may want to take heed as new data not only show that more than 2000 falsely convicted of serious crimes have been exonerated in America in the past 23 years, but the number of annual exonerations has grown consistently each year.

These findings are just now coming available as nearly 900 of these exonerations are profiled, with searchable data and summaries of the cases on the National Registry of Exonerations, a new joint project of the University of Michigan Law School and the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University. The Registry, available at exonerationregistry.org, will be updated on an ongoing basis. It represents by far the largest collection of such cases ever assembled – and the most varied.

As the report documents there are many more false convictions and exonerations that have not been found – moreover, those that have been found only account for a small subsection of the total number of people wrongly convicted.

“The National Registry of Exonerations gives an unprecedented view of the scope of the problem of wrongful convictions in the United States,” said Rob Warden, Executive Director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions. “It’s a widespread problem.”

“It used to be that almost all the exonerations we knew about were murder and rape cases. We’re finally beginning to see beyond that,” said Michigan Law professor Samuel Gross, editor of the registry and an author of the report. “This is a sea change.”

The report includes the following cases, most of which do not appear in any previous compilation:

- 58 exonerations for drug, tax, white collar and other non-violent crimes.

- 39 exonerations in Federal cases.

- 102 exonerations for child sex abuse convictions.

- 129 exonerations of defendants who were convicted of crimes that never happened.

- 135 exonerations of defendants who confessed to crimes they didn’t commit.

- 71 exonerations of innocent defendants who pled guilty.

According to Professor Gross, the cases in the registry show that false convictions are not one type of problem but several that require different types of solutions.

- For murder, the biggest problem is perjury, usually by a witness who claims to have witnessed the crime or participated in it. Murder exoneration also include many false confessions.

- In rape cases, false convictions are almost always based on eyewitness mistakes – more often than not, mistakes by white victims who misidentify black defendants.

- False convictions for robbery are also almost always caused by eyewitness misidentifications, but there are few exonerations because DNA evidence is hardly ever useful in robbery cases.

- Child sex abuse exonerations are almost all about fabricated crimes that never occurred.

“It’s clear that the exonerations we found are the tip of an iceberg,” said Professor Gross. “Most people who are falsely convicted are not exonerated; they serve their time or die in prison. And when they are exonerated, a lot of times it happens quietly, out of public view.”

As Professor Gross and Shaffer write in their report, “It is essential to put these numbers in context. No matter how tragic they are, even 2,000 exonerations over 23 years is a tiny number in a country with 2.3 million people in prisons and jails.”

However, many stop at this point and use this fact to defend the system. The problem is that the problem of wrongful convictions goes far deeper than anyone wants to acknowledge.

“If that were the extent of the problem we would be encouraged by these numbers. But it’s not. These cases merely point to a much larger number of tragedies that we do not know about,” the researchers write.

They add: “The most important conclusion of this Report is that there are far more false convictions than exonerations. That should come as no surprise. The essential fact about false convictions is that they are generally invisible: if we could spot them, they’d never happen in the first place.”

“Why would anyone suppose that the small number of miscarriages of justice that we learn about years later – like the handful of fossils of early hominids that we have discovered – is anything more than an insignificant fraction of the total?”

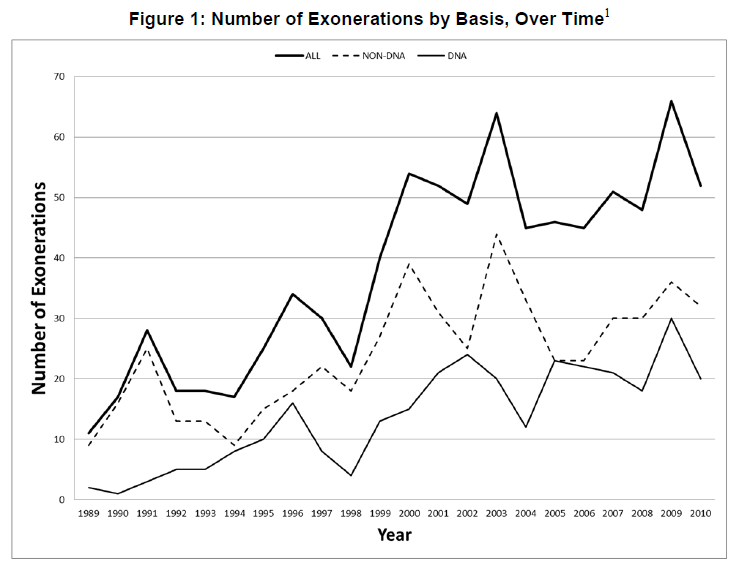

What we do know is that the numbers have increased over the past 21 years and while the belief there is that DNA-based exonerations drove this data, the chart that they provide shows otherwise. Non-DNA exonerations have always outnumbered DNA-based exonerations and we figure that number will continue to climb.

There is another point that illuminates the likelihood that the number of wrongful convictions is far higher than anyone knows.

The research by Professor Gross and Shaffer show that eighty-three percent of known exonerations were in rape and homicide cases – crimes that together constitute just 2% of all felony convictions.

They write, “The problems that cause false convictions are hardly limited to rape and murder. For example, in 47 of the exonerations the defendants were convicted of robbery compared to 203 convictions for rape, even though there is every reason to believe that there are many more false convictions for robbery than for rape.”

In both instances, rape and robbery, “the false convictions we know about are overwhelmingly caused by mistaken eyewitness identifications – a problem that is almost entirely restricted to crimes committed by strangers – and arrests for robberies by strangers are at least several times more common than arrests for rapes by strangers.”

Moreover, unlike in rape, DNA evidence rarely is useful in providing the basis for innocence of robbery defendants.

“Why do so few rape and murder convictions with comparatively light sentences show up among the exonerations?” the researchers ask.

They offer this possibility: “Most innocent defendants with short sentences probably never try to clear their names. They serve their time and do what they can to put the past behind them. If they do seek justice, they are unlikely to find help.”

In fact, they note, “The Center on Wrongful Convictions, for example, tells prisoners who ask for assistance that unless they have at least 10 years remaining on their sentences, the Center will not be able to help them because it is overloaded with cases where the stakes are much higher.”

Moreover, one thing that we have noticed in our court coverage is that smaller cases often have a lot more problems than larger ones, because police and investigator for the DA’s office invest more heavily in proper investigations of more serious crimes.

That leads us to believe that the number of wrongful convictions may be far higher in lighter cases than in rape and murder cases.

The first step toward fixing the problem is figuring out as much as we can about the problem.

According to Rob Warden, “This is a good start – a milestone – but there’s a long way to go before we have a complete picture of wrongful convictions in the United States.”

“We’ve begun to find exonerations that don’t fit the mold we’re used to – some that were initiated by prosecutors or police, and some that were deliberately concealed – but we know there are many more that we haven’t found, at least not so far,” said Professor Gross.

“If you’ve been exonerated and aren’t in this Registry, or if you know someone who has been exonerated and isn’t included, we want to know about it,” said Professor Gross.

“The more we learn about false convictions, the better we’ll be at preventing them – or if that fails, at finding and correcting them as best we can after the fact,” said Professor Gross.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

the country is over 200 years old. Lets say 200. 20/200 is ten percent of the time.

The data do not go back 200 years, so I don’t get your post.

exactly.

we need a more complete picture over a larger time period.

91 Octane

I also am confused by your post. This is probably because I relate better to words than to numbers. Could you restate your premise in words and explain its significance to you in words ?

It should be noted that there have been 2,000 exonerations out of roughly 23 million felony convictions over the last 23 years, which is approximately .008% exonerated, if I have read a recent article on exonerations correctly.

See: [url]http://www.timesunion.com/news/article/Study-2-000-convicted-then-exonerated-in-23-years-3571973.php[/url]

Now of course we know that the number of exonerations is not necessarily reflective of how many false convictions there are. The 2,000 exonerations certainly are a sign that the system is far from perfect. There really is no way of telling how many wrongful convictions there have been. But you cannot look at the number of exonerations (2,000) in a vacuum. When compared to the total number of convictions (roughly 23 million), the number of exonerations is tiny…

“

we need a more complete picture over a larger time period.”

This is the first step towards getting a more complete picture. Some of the things that we have learned and the advent of DNA precludes going back much further. The bigger and important question is what is happening now.

Elaine:

I agree the number is tiny. Then again, for Maurice Caldwell or Edward Carter, the number one was too many.

I see as attempting to start understanding what the real number is. Really their comments which I quoted address your point and my concern.

Frankly, I think the real number will be impossible to ascertain… and in some ways may not be that important. As you point out, if you are the innocent person sitting in jail, the exoneration rate is hardly of much importance…

However, I suspect that the accuracy of our justice system probably fairs better than that of other countries, e.g. Italy. And because of DNA testing has the chance of massively improving if we make DNA testing a requirement when it would be relevant. There are also many other improvements we can facilitate…

Elaine: If we are better than other countries, that only means things are more unfair elsewhere, not that they are fair here.

As the chart above shows, DNA is not going to be as much of a help as you think. Particularly since DNA only enters into a tiny fraction of cases itself.

Interesting article.

Presumably some rigorous investigations have been done to detail what specific factors led to each erroneous conviction? Eyewitness mis-identification and false confessions were cited.

For the cases of eyewitness mis-identification; review how the eyewitnesses arrived at an identification (line-up, photos, etc.)and the nitty-gritty details of how the mis-identification may have occurred.

For the cases of false confessions; review the details of the interrogation techniques to find out if there are some interrogative techniques that can lead to false confessions.

Perhaps there are some common investigative techniques that led to these wrongful convictions; by identifying these techniques; can ensure that better techniques are used and reduce the future chances of erroneous convictions.

This is the first step towards getting a more complete picture. Some of the things that we have learned and the advent of DNA precludes going back much further. The bigger and important question is what is happening now.

or maybe those who put the graph up don’t want us to see the larger truth?

[quote]As the chart above shows, DNA is not going to be as much of a help as you think. Particularly since DNA only enters into a tiny fraction of cases itself.[/quote]

My quote: “And because of DNA testing has the chance of massively improving if we make DNA testing a requirement when it would be relevant. There are also many other improvements we can facilitate…” DNA is only one of many possibilities for improving the justice system…

[quote]Elaine: If we are better than other countries, that only means things are more unfair elsewhere, not that they are fair here. [/quote]

That may be true, but I think it is important to put this in context. If our system is the most accurate thus far, then it is not a large stretch to assume we are doing some things right that other countries are not. Certainly there is need for improvement, but I guarantee there is no perfect system and never will be…