This week, the city of Vallejo, emerging from bankruptcy, is becoming the first city in the nation to allow, on a citywide basis, residents to vote on how to spend the city’s tax money.

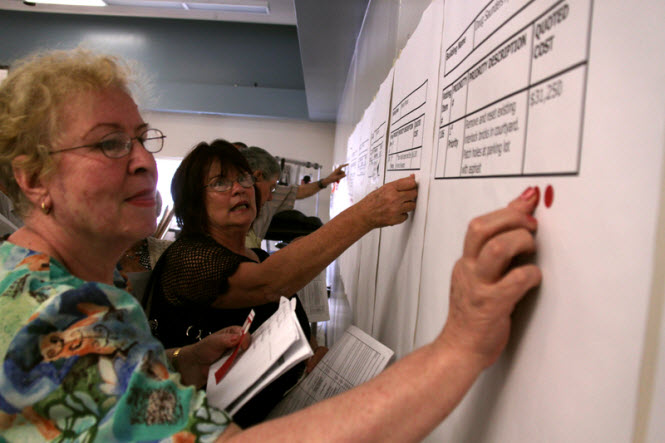

Under Vallejo’s model of “participatory budgeting,” residents ages 16 and up can vote on how to spend about $3 million in tax money. Residents will have an opportunity to view the ideas created by volunteer budget delegates representing a number of different committees, including education, economic development, youth and other segments of the community. Delegates worked with fellow committee members, City of Vallejo staff, city agencies, and local non-profits to determine which projects are feasible and most needed.

The city has allocated about 30 percent of a sales tax measure’s revenue, collected over a 15-month period, for this process.

Last week, Councilmember Lucas Frerichs, in noting the lack of public participation during the budget discussion, told his colleagues he was interested in pursuing participatory budgeting.

He pointed out, “I would be remiss to say that when (Mayor) Joe (Krovoza) calls for public comment, on this item, you can literally hear crickets in the room because it’s so quiet and there’s not really anyone in the room to make public comment whatsoever on an item that is as important as this.”

A big advocate for Participatory Budgeting is Nancy Price, who sees it as a “a tool that gives authority to the citizens of Davis to participate directly in the ‘construction’ of city budgets and setting priorities through a process of neighborhood and city-wide discussions and negotiations.”

“I bet if this process had been in place the past years, funds would not have been spent on different and essential priorities and would have represented the will of the people and not the political priorities of City Council members,” she pointed out in a comment earlier this week on the Vanguard. “Would the community have agreed to creating the huge unfunded liabilities for the police and firefights; would road maintenance have been neglected; would $6 and now $10 million have been spent on a water project before there was any vote what-so-ever of the people?”

But not everyone agrees. One councilmember told the Vanguard that participatory budgeting may be fine for five percent of the budget, but it would be a disaster for the whole budget. That councilmember suggested that they were elected to make tough budgetary decisions.

At the same time, the city is going to need to make critical decisions as to which programs and services to prioritize. We will have discussions about parks, recreation programs, and core services like fire.

We will also have to make the decision as to whether to seek new revenues to maintain our roadways or fund additional public safety officials.

Some of these issues will rely on the public – just as they did the surface water project – to approve new revenues, whether they be sales tax measures or parcel tax measures.

A new study in the peer-reviewed, The American Review of Public Administration, finds that public involvement early in the budget process, and doing so in multiple different ways, is positively associated with better performance of outcomes.

An article Monday in Governing laments the same dilemma faced by the city of Davis – the few times when the city of Davis has conducted public outreach, such as August 2011, the attendance and participation levels were low.

Writes Governing, “State and local government meetings, from a state agency to a county board, are notoriously low in attendance. Some governments have reacted with experiments to spur better public involvement, especially in drafting budgets.”

“Despite this patchwork of efforts to involve citizens, public administrators still don’t know exactly when to seek public input and how it might affect the day-to-day work of governing,” the article continues. “So Hai Guo and Milena Neshkova, both assistant professors in the Department of Public Administration at Florida International University, set out to study the relationship between citizen participation in budgeting and measurable performance outcomes.”

The analysis relied on 2005 survey data on state transportation agencies and their civic engagement strategies (focus groups, for example), across four stages in the budget process.

By looking solely at transportation agencies, the outcomes they looked to were fewer fatalities and better quality roads.

“They took into account external factors, such as level of funding, that might account for differences in fatality rates or road conditions. They found that not only is there an inverse relationship (more attempts at civic engagement mean fewer fatalities and low-quality roads), but that the relationship is statistically significant. In other words, the result isn’t due to chance,” Governing notes.

Furthermore, they found the strongest impact at the earliest stage of the process.

“You need to engage them early. I think that’s the point we’re trying to make,” Professor Guo said.

The study was narrowly conducted, so the next question is whether researchers would the same pattern emerging at other levels of government.

The good news is that Davis can sit back and observe nearby Vallejo to see how their process works. If Davis followed the model of Vallejo, they would look toward only a small portion of the budget.

And perhaps the best issues would not even be budgeting issues, but rather priorities. Right now, the city of Davis faces a variety of challenges.

First, they are faced with over $150 million in deferred maintenance on streets. Second, the city now faces a shortfall on water revenue. Despite the fact that the citizens voted to raise their water rates (indirectly on Measure I but more directly in failing to protest through Prop 218), the city faces a general fund hit of $3 million due to rising water rates.

That impacts not only the city’s general fund, but funding for parks and greenbelts.

The city is proposing cutbacks for fire, and some have called for more police officers on the streets.

The result is that budget priorities, which have rarely been discussed, must be worked out. Also, the city will be looking at new revenues.

Councilmember Frerichs last week called for an earlier engagement of the public on these issues. We suggested perhaps a WAC-type body looking into budget priorities, but that idea has been met by criticism from some who worry that would open the process to more influence from mobilized special interests.

What I would argue – which I have argued for some time – is that we have never prioritized spending and which programs and services are essential, and we have never engaged the public on these issues, as well.

From that limited vantage point, I think it would make some sense to reach out to the public. And if we cannot gain the general public’s interest outside of elections on tax or rate increases, we must look to other ways to engage.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

If there is very little interest in budget issues in general (and notably in this topic on the Vanguard, apparently), why would you seek to set up a participatory process? There is a great risk of the process being taken over by small activist groups who don’t represent the broader interest of the public. We did have a good model with the Housing Element Task Force, but it took a massive amount of citizen work, many hours, and lots of staff resources.

I think most people expect their elected representatives to deal with the general goals of budgeting, leave the details to the trained professionals on the staff, and only get interested when their particular service is threatened. My guess is this would be a waste of time and resources. It doesn’t seem there is a groundswell of interest in budget processes.

That’s a fair point Don, I think most people pushing this would be guarding against a repeat of the last decade.

“There is a great risk of the process being taken over by small activist groups who don’t represent the broader interest of the public. “

That is certainly what occurred when Sacramento promoted this type of process in the late 90s . That encouragement and empowerment of NAGs has made governing this city nearly impossible .

It depends on how participatory budgeting is implemented.

In some implementation, a special interest group will have no [b]leverage[/b] to affect the outcome for their own benefit because they have no power to control more than their own share of the budget. (See this post ([url]https://davisvanguard.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=6297:commentary-public-disengaged-on-the-budget-process&catid=58:budgetfiscal&Itemid=79#comment-180258[/url]))

I do not share the perspective that councilmembers are elected to make tough budgetary decisions. I think we have a grandfathered governance system, and I make my choices to reduce dogmatism in governing to limit the damage of misgovernance. I am not interested in the current budgetary process because as long as councilmembers think that they are the only ones who should be making those decisions, they are also not listening. That means that it is a waste of my time to be engaged in the process.

No councilmember should be proud for being elected to “make tough choices.” A councilmember should be proud when they equip every member of the community to make tough choices. The test of leadership is in making decisions for your followers, but in the ability to bring everyone up to their level.

I agree with Don.

We elect officials and hire city staff to determine spending priorities and manage the budget. The level of detailed information required to be an effective objective contributor to prioritization decisions exceeds the time capacity of most citizens having the brain power to handle it.

Also, those motivated to participate will be those with the strongest narrow focus self-interests.

In by business, there are two budget categories: fixed and discretionary. I think we could ask for city input to help prioritize discretionary spending goals. However, this should be at least one step removed from any participation that sets up participant expectations that they have a more powerful stake and/or influence in these final decisions. I would use survey tools instead of workshops.