It was mid-May when Jerry Brown, a lifelong opponent of the death penalty, met with prosecutors who are seeking to end California’s death penalty moratorium.

As the Sacramento Bee‘s Dan Morain reported on May 15, San Bernardino County District Attorney Michael A. Ramos, one of the prosecutors fighting California’s death penalty moratorium, now in its seventh year, after meeting with Governor Brown wrote, “After a respectful discussion about our philosophical differences regarding the death penalty, we discussed what the law is and how the people voted for capital punishment. He understands the vote of our citizens.”

“A lot of people in my world weren’t sure where the governor was on the single-drug protocol,” Ramos told Dan Morain by phone. Mr. Morain reported that the prosecutor is taking the governor at his word. “At this time – unless something strange happens – as far as this DA is concerned, I consider him a partner of mine in fighting for justice.”

However, that deal is out the window and California’s death penalty may be as well as the San Jose Mercury News reported on Friday, “Ensuring California’s death penalty system remains in limbo for the foreseeable future, a state appeals court on Thursday scrapped the state’s latest attempt to update its lethal injection procedures. In a 28-page ruling, the 1st District Court of Appeal found that state prison officials failed to comply with administrative rules when crafting new regulations more than two years ago.”

In 2011, the trial court granted a motion for summary judgment, finding that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) had “substantial[ly] fail[ed] to comply with the mandatory procedural requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act” when it adopted the regulations.

As the court notes, “The CDCR admitted below, as it does here, that it did not actually comply with many of the requirements of the APA that respondents claim constitute a substantial failure to comply.”

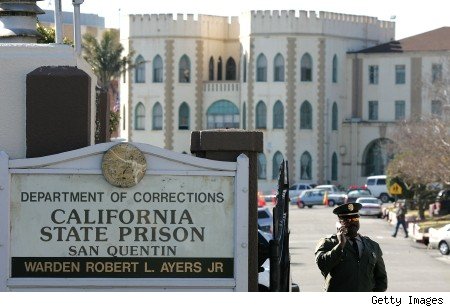

In short, the appellate court has upheld the ruling by a Marin County judge who “faulted the prison department for a variety of procedural missteps, including offering no public explanation for why San Quentin officials opted to continue with a three-drug lethal injection method instead of a single-drug execution option being embraced by a number of other states.”

The Mercury News goes on to report, “State officials have indicated in court papers they are exploring the single-drug option, which involves putting condemned inmates to death with one dose of a sedative. Ohio, Washington and Arizona are among the states that have moved to that option to short circuit legal challenges to the three-drug method.”

In a brief press release, Michael Risher, staff attorney for the Northern California ACLU, wrote, “Our prison system has, once again, completely failed to comply with state law when it adopted a problematic procedure for carrying out lethal injection executions.”

“Given that there is now no legal protocol for lethal injection executions, no known legal source for the drugs, and that manufacturers worldwide are increasingly reluctant to make them available, it’s hard to imagine how California will ever again be able to carry out another execution without continuing to flout the law,” he writes.

The decision on Friday, he writes, “should not come as a surprise.” He writes, “The government admitted that it had violated the law in numerous ways, and the lower-court judge had already struck-down the regulation. But it is an important one because it confirms both that the people of this state have a right to be heard when the government is making decisions and also that the government, like the rest of us, must follow the law.”

“For most of a decade, multiple judges on both state and federal courts have repeatedly held that California’s execution procedures are fundamentally flawed and in violation of both state and federal law,” Mr. Risher continued. “One would think that these multiple rulings would prompt the government to reevaluate its entire approach to its execution procedure; but, instead, its approach has been to tinker around the edges, ignore the fundamental problems, and then try to convince the courts that they have solved all the problems. Not surprisingly, the courts have not been impressed.”

Activists, many of whom led the way on a proposition that was narrowly defeated last November to commute all death sentences to life without parole, wrote, “Thirty-five years and $4 billion later — we are back to the drawing board. The only workable solution is for Governor Jerry Brown to convert all death sentences in California to life in prison with no possibility of parole.”

In an open letter to Governor Brown, they write, “The death penalty in California is broken and beyond repair.”

“California must now start over from scratch and embark on another attempt to create a legally sound lethal injection protocol, even as the state struggles to find legal supplies of execution drugs,” they write. “Governor Brown, we urge you to use your executive power and stop this ghastly charade that is enormously costly with no benefit to anyone. We cannot embark on another failed process that will waste even more public resources. Instead, we the undersigned, urge you to convert all 733 death sentences to life in prison without the possibility of parole so we can save money and ensure that California will never execute an innocent person.”

“This should be attacked on every front,” said Kent S. Scheidigger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation. “We have had justice held up for a preposterous seven years now.”

Natasha Minsker, an ACLU director who managed the campaign last year, said, “Any effort to resume executions will cost hundreds of thousands of public dollars and take years, with an extremely limited chance of success.”

“States that have gone to single-drug executions got their litigation dismissed pretty quickly,” Mr. Scheidigger told the LA Times. “The state of Washington adopted it in March, litigation was dismissed in midsummer, and they carried out an execution in the fall. That was six months from adoption to execution.”

But Natasha Minsker told the Times that “none of the drugs California has used in the past for executions are now legally available, and alternatives are fast disappearing.”![]()

“A few states have been using pentobarbital, but the manufacturer now refuses to sell it to prisons,” she said. ” A few states still have some on hand, but their supplies all expire by September. So that drug is not available as an option for California.”

Meanwhile, Denny Walsh of the Bee reports that Steve Mayer, who is lead counsel for the inmates challenging the regulations estimated it will take “at least nine months to a year, and maybe longer … if the state decides to craft revised regulations and jump through the rule-making hoops set out in the Administrative Procedure Act.”

Death penalty proponents want Governor Brown to fight the ruling. However, Mr. Mayer told the Bee that if the Governor’s administration petitions the Supreme Court to review the ruling it could take another two to four years.

The key quote, however, is this: “The CDCR did such a bad job. There wasn’t a single step in the process they did right, so it’s not surprising there is no case law right on point.”

—David M. Greenwald reporting

good for the drug companies that refuse to sell pentobarbitol to prisons!!

there are 10 people in CA alone who’ve been exonerated (by DNA evidence) after being sentenced to death row. kind of scary when you imagine that there’s probably not DNA evidence available for every convict. I wonder how many innocent folks are on death row at present? Are we certain it’s zero? because innocenceproject data on nationwide exonerations to date would cause one to extrapolate and say ‘no’.

when i was young and naive and believed in what i learned in social studies about due process, that it was the reality, i was for the death penalty (in my defense i grew up in a very conservative home in the south). i’m hopeful that before i die, kids will be learning in social studies about how the US ‘used to have’ the death penalty, the way my kids learned (and wondered at the insanity) of how they ‘used to have’ enforced segregation, not so long ago.

Gov. Brown said last year it was zero the number of innocents on death row. I asked Don Heller about that claim last year, he laughed, and named at least half a dozen where their guilt is at least in question and believes there are more we simply do not yet know about.

addendum, i miswrote, there are 10 people who’ve been exonerated after being sentenced to other things, NOT death row. oops. so far there are no actual death row exonerees in CA, sorry.

still the wrongful convictions argue that the system is far from perfect, that as Gov Brown states that these people have ‘exquisite due process in CA’ (guess he wasn’t talking about the 10 exonerees), would argue that as our system is imperfect, regardless of how one feels about executing actual guilty people, in principle it’s an untenable solution (as well as fiscally wasteful though that ideally shouldn’t factor).

But we did likely execute an innocent, Tommy Thompson. He was convicted based on the testimony of a witness named Mr. Fink, who has been used by prosecutors to convict a number of people who were still alive to have their convictions thrown out.

that he was denied due process i don’t think is in doubt, and he was wrongfully executed based on that alone. But i think he was convicted on more than just one jailhouse snitch. he went to sleep and just woke up and she was gone? he slept through her being murdered on the living room floor? that prosecutors committed misconduct (which unfortunately isn’t criminally prosecuted), seems clear. that he’s innocent, i’m not so sure. i thought it was known that she was killed in the same room where he was supposedly sleeping. I looked it up, and found a lot of conflicting things, found an in bank brief issued I think from Supreme Court of CA, June 23, 1988. Granted, I know these are summaries of the defense and prosecution, and can contain errors, but they’ve got to be better than press, i think. I see a lot in the media on how this guy was a standup citizen with no criminal record or even arrest, etc. yet certain facts point to his guilt far and above Mr. Fink’s testimony. (and i don’t know if he’s guilty or innocent, i don’t know the facts). But he admits going to mexico to do some pretty heavily illegal stuff, and admits contemplating cocaine dealing, not your everyday standup citizen. and he admits leaving for mexico, a couple days after the disappearance of this woman. He also states (according to Supreme Court summary) that while they were both in Mexico David Leitch told him he killed the victim. Yet as a standup guy, he didn’t bother to phone police and let them know. He stayed on in Mexico, and was arrested by authorities there and returned here to face murder charges.

from an armchair perspective based on admittedly limited data, this guy doesn’t sound like the innocent kindly man described in the press. my gut feeling is that one of them stabbed the victim, and both were involved. i wouldn’t convict a man based on gut feeling, obviously, but he doesn’t look terribly innocent to me. and according to the summary he admits to knowledge of a murder and admits he failed to report it. doesn’t that make him an admitted accessory after the fact at the very least? i am not an atty.

if a friend of mine told me they’d committed a murder, i wouldn’t make a fuss (while talking to them, as i’d be too frightened to upset them). but then i’d run off immediately to the police because a.) a killer just told me he murdered someone and has thus made me a witness and therefore a liability, and b.) my sense of morality would compel me to do so, even in the absence of fear. i think most people if they were the kindly courageous man that Thompson is described as in the press, would have at least been courageous and kindly enough to report the murder of someone he is supposed to have cared about enough to have a relationship with. where’s the anger at Leitch for killing his lover?

having said that, he should never have been executed. misconduct appears to have been committed, and if i take the word of what i’ve read so far, that a higher court actually failed to rule as a result of their own mistake, therefore denying Mr. Thompson due process, it is completely nuts that he was executed. what is frightening about that, if true (and i’ll just take folks’ word that it is), is that there are no consequences for the people who made such an error. ‘sorry we never got around to your case, our bad, guess you’ll just have to be executed, so sorry.’ really?

and why did hte same judge (they were tried by the same judge, yes?) allow the prosecution to essentially lie while making their case (either they lied the first case or the second (Leitch’s) as their arguments were inconcistent. the bigger question is why isn’t that illegal and prosecutable? or is it illegal? and if so, why aren’t prosecutors who commit misconduct prosecuted?