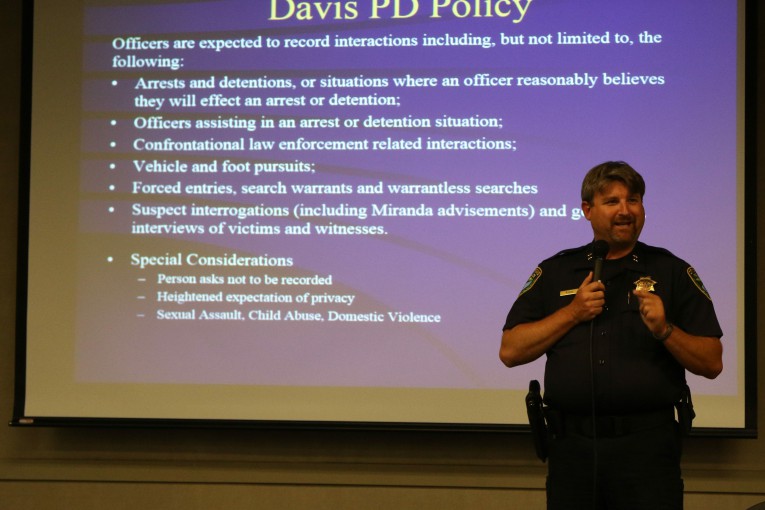

Last week Assistant Chief Darren Pytel laid out the Davis Police Department’s proposed body-worn camera policy.

As the assistant chief explained to the small audience at the Blanchard Room of the library, in many situations that the police encounter they are not enforcing the law, and there is an expectation of privacy. However, in situations that call for arrests and detention, or situations where an officer reasonably believes they will effect an arrest or detention, body cameras would be used.

These include officers assisting in an arrest or detention, confrontation law enforcement related interactions, vehicle and foot pursuits, forced entries, search warrants and warrantless searches, suspected interrogations including Miranda advisements and, generally, interviews of victims and witnesses.

“Law enforcement related events are going to be recorded,” he explained later. “Non-law enforcement events, the transactional things we do as cops – no enforcement is being done, they’re non-confrontational – those types of things, we don’t need to record.”

Following the presentation, Assistant Chief Pytel spoke with the Vanguard.

Assistant Chief Pytel said, “The biggest concern [of having the body-worn cameras] is having realistic expectations from the community that there are going to be incidents that are recorded, that doesn’t ultimately mean there is going to be video that is released right away.”

In some cases, with huge public demand, information would be released extremely quickly. “Because the video does exist, people want to make up their own minds and see it right away,” he said, “even though there’s legal justification or public policy consideration for not immediately releasing video.”

“I also think we’re going to start balancing people’s voyeuristic attitudes,” he said, where people take the position that a “juicy” story translates to a public need to see the video. “A lot of times those are going to be cases where there is a heightened expectation of privacy.”

Darren Pytel said, in terms of policy for video release, “as much as possible we’re going to follow the Public Records Act which exempts a vast majority of the video having to be released in criminal cases.”

It is the things that are non-law enforcement that cause the biggest concern. “There’s probably no justification for not releasing those video.”

They will have to resolve that issue by “not taking a video unless we’re prepared to have it disclosed.”

While this may have a bearing on the immediate public release of the video, Darren Pytel reminds the public that most of the time where there is a law enforcement action, the video will be “discovered” – it will just be discovered through a court of law and during legal proceedings, rather to the public through the media.

“Ultimately it’s going to be shown in court. Let’s preserve it for the investigation and let’s make sure that it’s actually used in the legally defensible manner,” he said.

However, the policy still leaves open the possibility that the police would disclose video that shows the department in a good light while withholding that which shows the department or an officer in less favorable light.

Ultimately, Darren Pytel stuck to the idea that such a video would come out but it would be in the court of law or during internal investigations. “If somebody takes some sort of legal action against us, the video is going to be discovered,” he said. “Yeah we may not release it to be shown on the 5 o’clock news that night, but ultimately the video is going to be discovered.”

This is an issue that every agency is going to have to balance. Mr. Pytel explains, “You have an officer involved shooting (and) people start raising questions about whether it’s a legitimate shooting or not.” In this era, “people want instant access to it and people want to instantly be able to make up their minds [and] until they see it or hear for themselves, there is that total lack of trust.”

He said that they cannot commit to releasing the video in those circumstance. They have always taken the approach that they won’t release the video unless they legally are compelled to do so.

In a follow up, the chief made it clear that the current policy of Davis PD is to not release any videos. However, one of the big debates is whether the police officers should be able to view the video prior to making their initial statements and writing their police reports.

As an alternative view, the Vanguard asked the ACLU for their policy guide.

BODY CAMERAS IN POLICING

In the wake of months of concerns about policing in America, many police departments and government officials are calling for the adoption of body cameras. As of January 2015, at least 72 police departments in the United States have adopted body cameras or established pilot programs for their use. President Obama has announced federal funding to help purchase 50,000 body cameras for police.

Do body cameras work?

The evidence on body cameras is limited, but promising. One widely cited study of body cameras in Rialto, California, showed dramatic results — officers who wore them used force half as often as those who did not, and were nearly 90% less likely to receive citizen complaints. But success in one small, suburban department (where the police chief, one of the study’s authors, clearly supported body cameras) does not assure similar results everywhere. The small handful of other studies do not show such clear results, although few police policies have been proven in controlled studies.

Some activists have expressed concern that body cameras won’t help hold police accountable, citing high-profile incidents like the Eric Garner case, in which a grand jury declined to indict an officer despite graphic footage of the incident. By providing better evidence of what actually happened, video will hopefully help factfinders hold officers accountable for misconduct that would harder to prove using witness accounts alone. But even if the video of Eric Garner’s death did not lead to the indictment of the officer involved, its powerful images helped the public question whether systems to hold officers accountable might be broken, and — like that of the Rodney King video over twenty years before — spurred a national outcry and calls for change.

Does the ACLU support body cameras?

The ACLU of California supports police body cameras if they are used according to policies that assure accountability and adequately protect privacy and allow transparency. The ACLU of California is cautiously optimistic that, used properly, body-worn video cameras can help deter police misconduct and uses of force, provide evidence to hold officers accountable when misconduct does occur and to exonerate wrongly accused officers, and help the public understand how police operate.

But body cameras are only tools — whether they are helpful or harmful depends on how they are used. Strong policies are crucial to ensure they further the goals of improved transparency and accountability, better policing, and greater trust in law enforcement.

However, body cameras aren’t a panacea. Video does not always capture the full story, and having video will not resolve every question. Many issues in policing that need addressing — from racial profiling and implicit bias, training on interactions with people with mental illness, limitations on surveillance, the availability of data on police actions and uses of force, transparency in officer discipline, and strong oversight and accountability mechanisms — require looking beyond individual incidents to patterns and systems. Body cameras may help police accountability, but they’re only a small part of the reforms we need.

Key Points for Body Camera Policies

For body cameras to promote trust between police and the community, police must use them in a way that carefully balances interests in police accountability, government transparency and privacy.

Rules to Promote Accountability

Clear Rules When to Record, with Minimal Officer Discretion —Body cameras don’t advance accountability if police can turn them off when they don’t want to be recorded. Officers should record all interactions with the public, and definitely all investigatory interactions (including consensual encounters). Very limited exceptions for sensitive situations (such as in instances of sexual assault or recording inside homes) should be permitted with clear, on-camera permission to stop recording.

Enforcing Compliance —Departments must enforce recording policies by auditing officers’ compliance and imposing meaningful consequences for failure to activate cameras or tampering with equipment.

Randomized Audits —Body camera footage should be subject to regular, randomized review to identify problems with training or officer conduct before they result in complaints or incidents. But supervisors shouldn’t target particular officers without complaints of misconduct for “fishing expeditions.”

Officer Review of Footage —Officers involved in a critical incident like a shooting or facing charges of misconduct should not be permitted to view footage of the incident before making a statement or writing an initial report. Police do not show video evidence to other subjects or witnesses before taking their statements. Officers should watch the video after their initial statement and have the chance to offer more information and context. Officers may not remember a stressful incident perfectly, so omissions or inconsistencies in their initial account shouldn’t be grounds for discipline without evidence they intended to mislead. This would provide the fullest picture of what happened without tainting officers’ initial recollection or creating the perception that body cameras are being used to cover up misconduct, not hold officers accountable.

Video Integrity — The public can only trust video evidence if there is no doubt officers cannot alter or delete the video they record. The devices must allow no way for officers to edit or delete video during the shift or the upload process, or after being uploaded to a secure server, until the retention period has elapsed. Even after routine deletion, records of access and deletion should be retained.

Rules to Protect Privacy, Create Transparency and Allow Public Access

Notice to People Recorded — Recording someone secretly is more invasive than doing so openly. Whenever possible, officers should notify people that they are being recorded, either by telling them or by having cameras clearly marked with a notice that the encounter may be recorded.

No Use for Surveillance —Body cameras shouldn’t be used for surveillance of the public, especially gathering of intelligence information based on First Amendment protected speech, associations, or religion. Departments should bar review of video unless there’s specific reason to believe that it contains evidence of a crime or misconduct, or as part of a randomized audit, and should prohibit analysis of video with other surveillance tools, such as facial recognition technology.

Public Release —Setting the right balance between privacy and transparency in public access is tricky, but some situations are clear. Videos of public importance (such as those of a shooting or other serious use of force, or other potential misconduct) should to be made public. Those with highly private footage, such as inside a home, should remain private. Where possible, agencies should protect privacy by anonymizing civilians’ features and voices through blurring and audio alteration, if doing so can still further transparency.

Civilian Access —Giving people video of their own encounters with law enforcement does not raise privacy concerns. Civilians recorded by body cameras should unquestionably have the right to obtain copies of those recordings for however long the government maintains them.

Transparent Process —As with any surveillance technology, department policies governing body cameras and the resulting video should be developed through an open process with public input. The process of developing and finalizing policies must be complete before the devices are deployed.

“They have always taken the approach that they won’t release the video unless they legally are compelled to do so.”

Thus engendering the very sense of distrust that the police seem to believe is unjustified.

““people want instant access to it and people want to instantly be able to make up their minds [and] until they see it or hear for themselves, there is that total lack of trust.”

Yes, it is true, and in my mind justifiable that people want transparency in policing just as they do in other areas of their lives. To say that you will not release information until you are legally compelled to do so is to invite the belief that you are deliberately hiding something. This is true of any entity. It is amazing to me that the police seem to decry a “lack of trust” when they maintain this policy. Is it any wonder that people want to “see for themselves” when our legal system is based on an adversarial approach where every piece of evidence, every statement, every bit of footage is “spun” by each side to its own advantage ?

This is a ridiculous demand. How about we put a camera on every doctor to record every patient encounter to help vet claims of malpractice but disallow the doctor from reviewing the videos to review what actually occurred?

The ACLU has degraded into just one of the gears in the machine of anti-law enforcement while also exploiting anything and everything they can use in the political groupism wars favoring the left.

Democrats are owned by the liberal wing who also own the labor unions, the universities, the main media, scientists and lawyers. So all these entities are complicity in political malfeasance to benefit the Democrat party that returns favors to the entities.

I defend law enforcement but at the same time see it as having made a deal with the devil. Police are represented by their labor union and their labor union is part of one of these Democrat-owned entities. And Democrats, with help from their lawyer friends in the ACLU, are using the police as a scapegoat for the otherwise obvious evidence that the lawlessness that cops have to deal with is the result of decades of failed liberal policies.

Body cams are supported by most people. And so we have a consensus for moving forward with improvements. Yet the ACLU won’t accept it unless it is 100% done their way.

And here is the reason folks. The ACLU’s stock and trade are cases against law enforcement. They actually do not like the use of cameras because it will tend to implicate more of their clients as having behaved so badly to deserve the treatment they received at the hands of the cops. Make no mistake… the ACLU only wants the primary advantage of cherry-picking the video content to help perpetuate their stock and trade of cases against law enforcement.

That’s why I hardly ever give a doodoo what the ACLU or NY Times have to say.

bp – can you explain from your perspective why the aclu’s position is worse than the proposal from the davis pd?

“This is a ridiculous demand. ”

frankly – can you explain from your perspective why the aclu’s position is worse than the proposal from the davis pd?

Frankly,

“How about we put a camera on every doctor to record every patient encounter to help vet claims of malpractice but disallow the doctor from reviewing the videos to review what actually occurred?”

Interestingly enough, I think that this is a good idea for cases in which patients who would be willing to give their consent. There would be a number of potential positives for these tapes.

1)The would allow the doctor to see how she interacts with patients. Does she truly show compassion, listen without interrupting, does she clearly comprehend the patients concerns and address all questions in a manner the patient can understand.

2) With patient permission, they could be used as training examples for medical students and junior doctors.

3) The patients could be offered copies which could be played back at home to ensure that they understood the doctors recommendations and they could replay the information as needed.

4) If needed in the future, they would avoid the he said / she said that currently informs the discussion of whether a patient was adequately counseled prior to surgery or if they were appropriately warned of possible side effects before taking a drug.

In deciding of issues such as this, I think it is important to weigh the possible good outcomes rather than just dismissing an idea ( not a “demand”) as ridiculous.

The Rialto PD experience with body cams, despite it remarkable success, was diminished by the community being portrayed as “small suburban” town.”

Rialto is over 100,000 population and has a police force twice the size of Davis. The demographics show a white minority, 22% African American, and a substantial Hispanic population. While Davis may be Mayberry, Rialto is surely not. That makes the 90% reduction in citizen complaints after the introduction of body cams all the more telling, despite the apparent ACLU effort to trivialize and isolate.

But no matter, the 900-pound gorilla just walked in. In Today’s Los Angeles Times, the Police Commission authorized the acquisition of 7,000 body cams for all its patrol officers. The ACLU was in attendance, vigorously put forth its terms for acceptance, and was rebuffed by the Commission.

http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-lapd-body-cameras-rules-20150427-story.html#page=1

For the sake of diversity, if nothing else, could we include policy guidelines on body cams from the federal government and how it compares with the ACLU agenda? The more the ACLU speaks on body cam policy, the more contradiction, confusion, and levels of ambiguity. The Department of Justice is giving out body cams throughout the nation, and supplies operational policy along with it.

Good point. I think it very necessary to learn what the Dept of Justice view is on the matter.

ACLU: “Enforcing Compliance —Departments must enforce recording policies by auditing officers’ compliance and imposing meaningful consequences for failure to activate cameras or tampering with equipment.”

This part of the ACLU’s guidelines I agree with wholeheartedly. There must be some consequence for a failure to record in a situation where it is clearly called for. Otherwise the police will just turn off their cameras or “lose” the pertinent video footage in situations unfavorable to law enforcement. This has happened. See:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-watch/wp/2014/03/26/police-cameras-are-great-except-when-the-video-goes-missing/

Watch this video – it is absolutely shocking:

http://www.msnbc.com/all-in/watch/missing-video-in-the-laquan-mcdonald-case-453667395733

I am not sure how I feel about releasing video to the public, in situations of a police shooting for instance. Two people can view video footage of the exact same event, and come to completely different conclusions about what happened. This could unjustly whip up public sentiment. However, I also understand the public’s feeling of a “need” to know. I think my biggest concern is not whether to release the video to the public, as much as it is about video footage going missing for unexplained reasons. Thus in a court of law, I would prefer that in officer shootings where they are required to wear body cameras, a burden of proof is required that police officers produce video footage. If they fail to do so, then the presumption should be that the officer erred in carrying out his duty, and s/he would have to rebut that presumption.

i share the belief expressed in the article as long as the policy is evenhanded – all in or all out, i think we can live with it as long as there is oversight. since davis has a police auditor, we are good.