In 2007, led by Councilmember Lamar Heystek, the Davis City Council created an ordinance requiring 2:1 agricultural mitigation for all development projects on the Davis periphery under all circumstances. At the time, the council voted to exempt agricultural projects of less than 40 acres from adjacent mitigation requirements.

The idea behind mitigation is that any development along the periphery of Davis would require the developer to concurrently set aside twice as many acres to be protected and preserved as agricultural land.

As City Staffer Mitch Sears said at the time, the idea of adjacency is to address the outward expansion of the city so that larger tracts of farmland are protected. In a response to a question from Councilmember Don Saylor at the time, Mr. Sears explained, “The primary threat to farmland in the central valley is urban expansion.”

That ordinance took language from the Davis General Plan: “In order to create an effective permanent agricultural and open space buffer on the perimeter of the City… peruse amendments of the Farmland Preservation Ordinance to assure as a baseline standard that new peripheral development projects provide a minimum of 2:1 mitigation along the entire non-urbanized perimeter of the project.”

The county, in their agricultural conservation and mitigation document from August 2015, actually goes a step further, noting, “Agricultural mitigation shall be required for conversion or change from agricultural use to a predominantly non-agricultural use prior to, or concurrent with, approval of a zone change from agricultural to urban zoning, permit, or other discretionary or ministerial approval by the County.”

With some exceptions, the county provides that “for projects that convert prime farmland, a minimum of three (3) acres of agricultural land shall be preserved in the locations specified in subsection (d)(1) for each acre of agricultural land changed to a predominantly non-agricultural use or zoning classification (3:1 ratio).”

For projects that convert non-prime farmland, the 2:1 mitigation would remain in effect: “…a minimum of two (2) acres of agricultural land shall be preserved in the locations specified in subsection (d)(1) for each acre of land changed to a predominantly non-agricultural use or zoning classification (2:1) ratio.”

Finally, for those projects that convert a mix of prime and non-prime lands, the requirement “shall mitigate at a blended ratio that reflects for the percentage mix of converted prime and non-prime lands within project site boundaries.”

One exemption is for “[a]ffordable housing projects, where a majority of the units are affordable to very low or low income households.”

Under the current mitigation provisions, the city requires agricultural mitigation as a condition for approval “for any development project that would change the general plan designation or zoning from agricultural land to nonagricultural land and for discretionary land use approvals that would change an agricultural use to a nonagricultural use.”

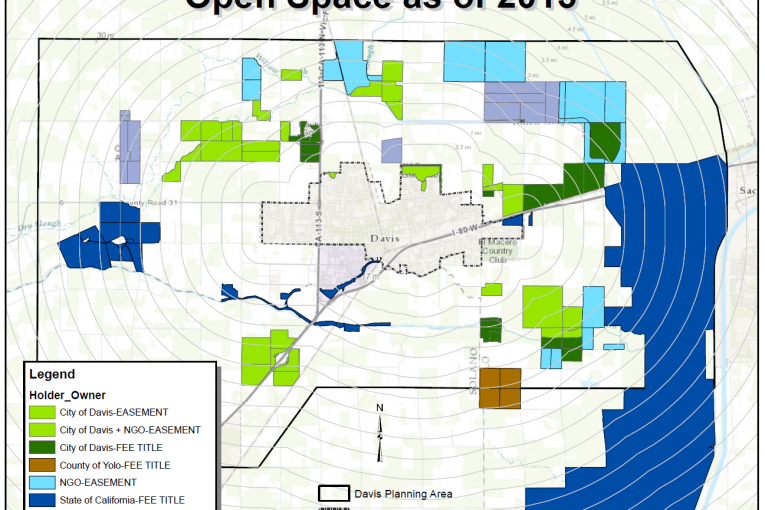

The city “has determined that effectively locating mitigation lands provides increased protection of agricultural lands threatened with conversion to non-agricultural uses.”

The city requires, “All new development projects adjacent to agricultural land that are subject to mitigation under this article shall be required to provide agricultural mitigation along the entire non-urbanized perimeter of the project. The required adjacent mitigation land shall be a minimum of one-quarter mile in width, as measured from the outer edge of the agricultural buffer…”

Why consider going to 3:1 mitigation?

First, it would create a more uniform policy with the county. At this point, almost all land that will be converted from agricultural use to urban use is county land that requires annexation. Under county rules, that land would need 3:1 mitigation if it is prime agricultural land. By implementing its own 3:1 requirements, the city would be creating a more uniform and coherent policy with the county.

Second, the notion of mitigation is not to prevent growth. Rather it sets forth a policy that any time the city grows, it creates a cap on the next step of urban explanation. The best way of maintaining urban encroachment is to preserve viable farmland.

Third, while some may see this as another anti-growth measure, an argument can be made that it might enable some limited expansion of urban uses. The public may be more willing to approve peripheral development if they know that they are locking in an urban limit line as they do so.

For instance, the Mace Ranch Innovation Center project proposes to convert 200 acres or so of farmland to urban uses. Under 3:1 mitigation, they would be required to set aside another 600 acres of farmland for permanent preservation.

Back in 2007, Councilmember Lamar Heystek argued, “We are situated in an agricultural landscape. I think it [this ordinance] makes votes under Measure J more of a balanced presentation. I think that some citizens may subconsciously support a Measure J decision knowing that we’re going to preserve more agricultural land in perpetuity than is being taken away.”

At that time, Mr. Heystek noted, “We will have the strongest agricultural mitigation ordinance and farmland protection ordinance in the state.”

However, the county has now surpassed the city in this regard. Ironically, expanding the open space protections of this ordinance may be a way of opening up some land for development, knowing that in so doing, we are protecting three times that land in perpetuity.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

i’ll be interested to see where frankly and misathrop come down on this. it might be a way to open up development.

Land use is land use. Land has a use-value to humanity especially in the region where the land exists. The county 3:1 mitigation rule makes more sense because: 1 – more of the county land is rural; 2 – the county should have more disencentives to develop on the preiphery of the cities in the county.

But pushing Davis to a 3:1 ratio rule from the existing 2:1 rule would be a brain dead move (unless you are a nogrowth and/or farmland preservation extremist). It would be brain dead because we already have Measure R and Measure O and so we already have plenty of “tools” to ensure the citizens can vet the pros and cons of preipheral land use and make an informed value decision.

Instead we should be talking about a 1:1 mitigation rule if the land is usable by the residents, and 2:1 if it is not.

Seems to me that the developers of the proposed MRIC (commercial) and Nishi could broaden their appeal, by offering 3:1 mitigation.

exactly. but i guess that’s brain dead

What appeal? Who would find it appealing? The nogrowthers? The old grumpy change-averse people? The land preservation extremists? The more recent Davis immigrants who, now that THEY are here, want to shut the door behind them?

Certainly not those concerned about the weak state of our local economy relative to our current and growing population.

Certain not those concerned about the city budget and our large and growing unfunded liabilities.

Certainly not those that care about jobs and economic opportunity for people that still need to work for a living and our young people… including our fabulously smart and talented UCD graduates.

Certainly not those that care about UCD technology transfer and helping grow the awesome and innovative ideas born in academia that need to move to a real business so they can help make the world a better place. Note… business needs land. And note 2… farming is just one type of business that needs land. And note 3… California has more prime farm land than we can farm.

I think it all boils down to our responsibility to help improve the human condition? Does a farmland moat promote ther improvement of the human condition, or is it just it just promote the selfish wants to a few?

Well, I’d (generally) find 3:1 mitigation more appealing.

If I were a developer (seeking to develop beyond city limits) I’d be looking for cost-effective ways to make proposals more appealing to voters. Probably less costly and risky, that way. (Might work better than slick advertising campaigns, as well.)

Sure, there will always be those who aren’t satisfied. (Also, it’s sometimes difficult to determine the value of any particular mitigation.) Still, I think that developers could do more, to gain support. (Developers are generally the party that is proposing a change, in the form of a development. Developments impact current residents, in ways that are often negative.)

Alternatively, we can continue on our current path of mutual distrust (between residents and developers). Lots of productive name-calling, etc. That’s always helpful. (I’m not singling anyone out in particular.)

I don’t understand this article. Is this an actual proposal for the council to act on?

If Utopian articles were agendized proposals, we’d all be unicorns.

utopian county policy?

what do you mean by an actual proposal? it’s an actual county policy right now. i doubt that the city has taken it up

I guess my question is what prompted this article.

Of course the more you raise the price then there are increased costs that get passed along. If there is no housing it doesn’t matter much but when you build housing it makes the housing all the more expensive when you increase the costs. So if people want to do this then they shouldn’t demand inexpensive housing at the same time. How much will this cost Nishi? Currently the margins are so great because we have under built for so long the developers can probably afford it but if we ever want to actually make living in Davis affordable this works against us lowering home and rent prices on new construction. Those of you that don’t want us to build homes will probably like that but I would prefer that we make it easier for people to live here not harder.

Alternatively, the increased costs of acquisition of land comes out of other “goodies”… to think it comes solely out of ‘profits’ is not “real”…