By Leanna Sweha

The Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) seems to stand in the shadow of Cap-and-Trade. Both are market-based programs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and spur new technology, but the LCFS tends to get less attention.

The LCFS is in fact a big regulatory program which stands to play an even bigger role in the proposed 2030 Scoping Plan, the roadmap to meet the state’s 2030 emissions goals. So, it’s important to ask if the LCFS has proven to be an effective policy tool.

The LCFS requires transportation fuels sold in the state to meet a target average Carbon Intensity (CI). CI is the sum of greenhouse gas emissions from the production, distribution, and consumption of a fuel, measured in grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule (gCO2e/MJ).

The CI calculation is called a lifecycle analysis (shorthand terms include “well to wheels” or “seed to wheels”) and is based on complex models.

Fuels with a CI below the target CI earn credits. Fuels with a CI above the target CI, such as gasoline, may be blended with low-CI fuels to meet the target. Or, their producers can buy credits from companies that produce low-CI fuels such as biodiesel, electricity, and hydrogen.

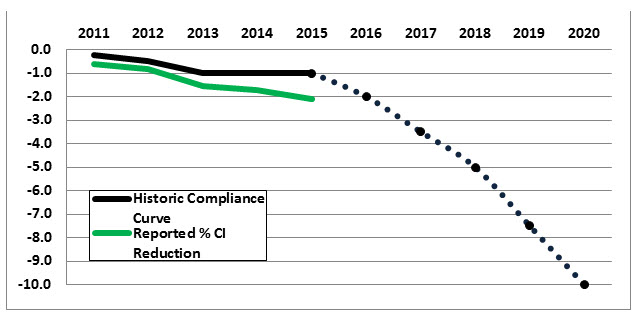

The target CI declines 10 percent below the baseline by 2020. In the proposed 2030 Scoping Plan, the target CI declines 18 percent below the baseline by 2030. That’s pretty steep, considering the curve to 2020 (see below) is back-loaded. The Air Resources Board says the back-loading was intended to promote early investment in alternative fuels and vehicles.

Two academics recently battled it out over the LCFS on the op-ed page of the Sacramento Bee. In January, MIT economics professor Christopher Knittel compared LCFS credit prices with Cap-and-Trade allowance prices. He showed that the marginal cost of reducing emissions with LCFS was on average six times greater than with Cap-and-Trade. He argued that this cost difference should convince California to end the LCFS and just rely on Cap-and-Trade.

In February, UC Davis Institute for Transportation Studies researcher Sonia Yeh responded to Knittel. She argued that one needs to look beyond the cost analysis and acknowledge that price signals from Cap-and-Trade alone would not be enough to force development of low-CI fuels. Yeh states that the LCFS is the only fuels policy that can spur market growth of alternative fuels and vehicles to de-carbonize transportation.

Meanwhile, oil companies are concerned about a short supply of LCFS credits and a short supply of low-CI fuels to blend with gasoline.

Commodities blog The Barrel reported last year, “The industry warns that insufficient quantities of alternative fuels will be available to meet the 10% CI reduction target by 2020, and that the state’s refineries could shut down or decide to export their fuel, rather than bear the cost of complying with the LCFS.”

It continues, “Holders of the credits appear to be hoarding them in anticipation of the CI reduction targets becoming harder and harder to achieve.”

According to Yeh, higher credit prices should drive up the supply of low-CI fuels and lower their cost.