(From Press Release) – District Attorney Jeff Reisig announced the release of a comprehensive “Four-Year Report on Neighborhood Court.” Initially developed by the District Attorney in 2013, in collaboration with community members and civic leaders, Neighborhood Court (NHC) is a criminal diversion program that is dedicated to finding more effective ways to deal with low-level offenses in Yolo County communities, than the typical offerings of the severely impacted “one-size-fits-all” criminal justice system. Neighborhood Court utilizes restorative justice principles while involving community members to resolve criminal cases outside of the traditional court system.

(From Press Release) – District Attorney Jeff Reisig announced the release of a comprehensive “Four-Year Report on Neighborhood Court.” Initially developed by the District Attorney in 2013, in collaboration with community members and civic leaders, Neighborhood Court (NHC) is a criminal diversion program that is dedicated to finding more effective ways to deal with low-level offenses in Yolo County communities, than the typical offerings of the severely impacted “one-size-fits-all” criminal justice system. Neighborhood Court utilizes restorative justice principles while involving community members to resolve criminal cases outside of the traditional court system.

A few highlights of the report include:

- NHC has resolved over 1,261 criminal cases since its launch in 2013;

- NHC is staffed by over 200 citizen volunteers from Davis, West Sacramento and Woodland;

- NHC has an 89% completion rate;

- A recent independent evaluation of NHC, completed in March of 2017, found that the recidivism rate for NHC participants was an incredibly low 4%!

The report addresses the program structure, analyzes participants and outcomes, explores the process for integration of this program into the current criminal justice system, discusses community engagement and outreach, reviews annual goals and achievements, examines challenges and policy recommendations, and presents the program’s future goals and intentions.

City of Davis Mayor Robb Davis noted that, “Neighborhood Court strengthens our city and enables citizens to engage in an approach to justice that builds accountability and offers a way for harms caused by crime to be made right.”

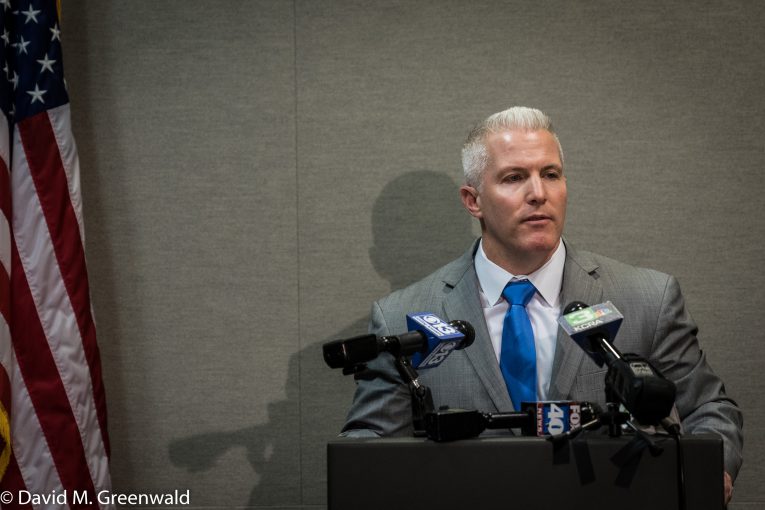

District Attorney Jeff Reisig stated, “Neighborhood Court is an outstanding example of innovative and effective local criminal justice reform. The success of the NHC program is wholly thanks to the support of community members, partners, public officials, stakeholders, and volunteers who have donated time, resources, and passion to this mission!”

From the report:

A young man and his wife stop at the local super market on their way back from a long day in the neonatal intensive care unit with their newborn baby girl. They are exhausted, stressed, and  struggling to make ends meet. They do not have much familial support to rely on, he was recently laid off and she only works part time at a local drug store due to the demands of their new baby. He feels bad that mother’s day was a week ago and he did not have enough money to get her anything. At the store, he tells her he has some extra money so she should pick out some items for herself. As they continue to shop, he hides the items inside her purse. They finish shopping, go to the register and pay for the items still in the cart. He does not acknowledge the items he hid, and she pretends not to have noticed. As they head toward the exit together a security officer approaches and asks them to step into a small office. There, they wait for a police officer to arrive and cite them for petty theft. Overwhelmed with guilt, the young man worries about his family and how they will handle this new problem on top of the daily challenges that they face.

struggling to make ends meet. They do not have much familial support to rely on, he was recently laid off and she only works part time at a local drug store due to the demands of their new baby. He feels bad that mother’s day was a week ago and he did not have enough money to get her anything. At the store, he tells her he has some extra money so she should pick out some items for herself. As they continue to shop, he hides the items inside her purse. They finish shopping, go to the register and pay for the items still in the cart. He does not acknowledge the items he hid, and she pretends not to have noticed. As they head toward the exit together a security officer approaches and asks them to step into a small office. There, they wait for a police officer to arrive and cite them for petty theft. Overwhelmed with guilt, the young man worries about his family and how they will handle this new problem on top of the daily challenges that they face.

A student goes out to a local bar with friends to celebrate her twenty-first birthday. At some point in the evening, after consuming several drinks, she decided to head home on her own. Officers found her alone, stumbling down a bike path, oblivious to the presence of officers, and headed in the opposite direction of her stated destination. She is unsteady on her feet, and does not have a phone or any means to contact friends or someone for help. Officers arrest her and transport her to jail for her own safety. This is her first time in trouble with the law and she does not know what to do. As she sobers up, she is mortified of what could have happened in her drunken state, and terrified of how this might affect her future.

These stories are all too familiar to residents of Yolo County. In the cities of Woodland, West Sacramento (WS), and Davis, a changing work force, economic struggles, and growing population of transition-aged young people, struggling with the uncertainties and trials of making the leap from youth to adulthood, are all factors that contribute to the crimes seen in this program. Within each crime, be it public intoxication, petty theft, resisting arrest, or any of the more than 60 eligible offenses seen in this program, the motives leading up to the offense can differ vastly. The consequences to the participant, the community as a whole, and others involved, can vary just as widely.

For years, the courts have worked to treat all misdemeanor defendants the same and levy a standard disposition regardless of the individuals behind the crime and their needs or the specific needs of the community. For first-time offenders, and those trying to change their ways, this can be especially harmful. The root of the issue often remains unaddressed, and the effects of an arrest and/or conviction in creating a criminal record, may only prove further hindrance to achieving gainful employment, professional licensing, financial stability, housing, reengagement with the community and avoiding future offenses. As the cycle of crime and punishment falls into an endless loop of recidivism, it is apparent that the traditional approach to criminal justice alone is untenable. Society is becoming increasingly frustrated, disenchanted, and even less engaged. The criminal justice system must be more innovative and creative. It is incumbent on criminal justice partners to lead the charge.

In 2013, spurred by this need for alternative, community based solutions, the Yolo County District Attorney spearheaded an innovative new diversion program called Neighborhood Court (NHC). With the first case taking place four years ago, this report will provide an overview and analysis of the goals, achievements, challenges, and future intentions, over the course of life of the program, by detailing:

- The program structure of NHC and the principles and reasoning for its format;

- An analysis of program participants and outcomes;

- The process for integration of this program into the current criminal justice system and processes;

- The approach to community engagement and outreach;

- A review of the program’s 2013 goals and achievements;

- 2014 goals and achievements;

- 2015 goals and achievements;

- 2016 goals and achievements;

- Addressing program challenges and policy recommendations to minimize barriers to program success; and

- The program’s goals and intentions moving forward.

To read the full report, visit: http://yoloda.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/NHC-4-yr-Report.pdf.