On Friday, M E Gladis’ piece, “Lincoln40 and the Issue of Bed Leases,” triggered a lot of stir when she argued, “Leasing by the bed bars students from doing the one thing that makes housing affordable for them in Davis – sharing bedrooms and splitting the rent – and it is reducing the number of beds overall in our town.”

While the writer makes some interesting points, I was skeptical of the data – in part because while the authors note that they used the 2017 BAE Urban Economics vacancy report, they also admit they extrapolated for the data.

“Calculated together, if all the bed leased units allowed for double-occupancy in their bedrooms, there would currently be an additional 3,318 beds in Davis,” but how realistic is it that all rental bedrooms would be double-occupancy?

Not only do many students not wish to share a room, but the bigger problem is that the rental figures are not really based on real data.

As a poster, Harry Chima, who seems to have worked on the original piece, notes: “It (their data) doesn’t include information about specific apartment complexes, only general trends.”

One of their points is that they are not anti-growth or housing, they simply believe that the city has under-utilized housing stock and they argue: “We think all units should be averaging double-occupancy in all their bedrooms.”

Clearly, that doesn’t seem reasonable. Nor does it seem likely that landlords would allow tenants to simply double up and not adjust the rent accordingly.

The biggest problem I see with the piece thus far is that they have not actually calculated the real costs of doubling up in the real world. They have simply extrapolated, and that seems problematic at best.

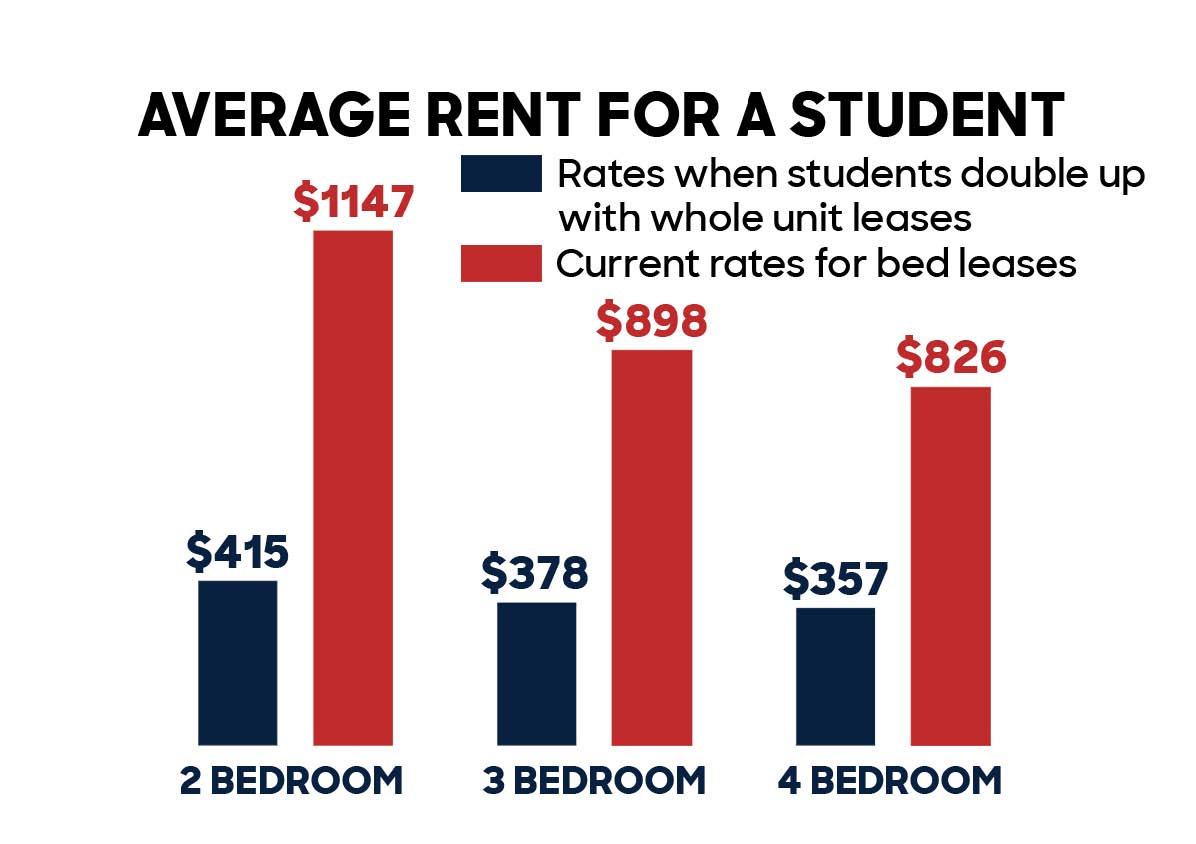

In short, this chart does not represent real data.

The writers argue that “because students can double or triple up in each bedroom with whole unit leases, they pay three times less than their bed lease counterparts.”

But there is nothing to suggest that is accurate.

On the right side is the calculated rate for bed leases, but there is no distinction between a bed lease for an individual room and a bed lease in a shared room. Thus the left side comparison point, which represents “rates when students double up with whole unit leases” is not only based on theoretical data, it is not even an apples to apples comparison – assuming the data is correct to begin with.

The left side is simply a matter of taking the average unit rent and dividing it by enough people to make each room double occupancy. The problem with that approach is that (a) it again assumes that every room can be double occupancy, and that (b) the landlord is not going to increase the cost of the unit rent when there are more occupants on the lease than rooms.

Neither one is necessarily accurate and it is definitely not happening in the real world.

Moreover, the right side of the analysis assumes there will not be a reduction in costs when the bed lease is in a shared room compared to when the bed leasee has their individual room.

There are also data limitations that prevent us from using the BAE data to figure out the answers to these problems.

The problem is threefold.

First, the BAE report does not compute separate averages for shared versus non-shared rooms. Indeed, they give a range for the costs per bed with a maximum and a minimum. But the data does not make a distinction between the two. There is no reason to believe that a bed in a doubled-up room will rent for the same cost as single-occupancy.

In fact, we know that in most cases a shared room will reduce the rent to the individual, but it just won’t reduce it completely in half (and for good reason from the standpoint of landlords).

The second problem is that the writers assume that by adding tenants to a unit lease, the landlords will simply allow more people into the apartment unit to share more of the costs. To some extent that may be true, but we don’t know it to be so.

In a comment they note: “For example, Arlington Farm Apartments will charge $950 for a single bed or $525 per bed if you want to double up – netting them an additional $100 for the same room if two people decide to room together. This kind of tactic isn’t possible with whole unit leases where landlords charge the same rent regardless of whether all the rooms are single occupancy or all of them are double.”

But the question is, will the landlords will charge the same rent regardless?

The Nishi rental analysis here is telling. Nishi is planning for unit rather than bed leases.

At the same time, the analysis shows that the average rent per bed for single occupancy is expected to be $1000, while the average for double occupancy market rate is expected to be $850.

That is in a unit-leased room. Nishi is not simply going to allow more students to jam into an apartment. They will have a lease and calculate the rent accordingly.

Clearly the assumption that landlords are going to allow students to jam into an apartment and split a set rent are questionable here. The market is such that this goes against their best interest. The landlords are quickly catching up to the market and it appears that any advantage that a unit lease has over a bed lease will probably evaporate, given the fact that this is a seller’s market with real scarcity of supply.

There is actually a third problem with the data. If you look at the bed lease situations, there are very few existing cases where the units are doubling up. For example, there are 70 one-bedroom bed-leased units, but just 83 beds. There are 252 two-bedroom units but just 526 beds. There are 279 three-bedroom units but 885 beds.

Only with the four-bedroom units does doubling up occur. But even here it is 625 bed leases, with 3010 beds. Even here we are talking 4.8 tenants per four-bedroom apartments.

In short, we do not have the statistical data to compare doubled-up bed leases because the number of doubled-up renters is comparatively small.

The bottom line is this, having double-occupancy rooms to reduce costs may work for some students, but those will come at a cost to the students in the loss of space and privacy. A cost that some will take in order to reduce costs, but hoping to double-occupy all rooms is foolhardy.

Second, the data in the chart above is simply not real and it appears that landlords will have mechanisms to prevent savings of that sort. Students can always attempt to go under the table and sleep on couches as a way to have savings, but if students are going to be on the lease, they are not going to get full savings.

More and more rental companies are monitoring how many live in each dwelling and will not simply allow double occupancy as a way to greatly reduce costs.

Finally, the analysis, while interesting, is not based on real world figures. It sounds good to create more supply and reduce rents by doubling up in rooms, but that comes with a cost and probably not as pure a savings as the authors would like to believe.

—David M. Greenwald reporting