During Wednesday’s discussion at the Planning Commission on the Affordable Housing Ordinance, several of the commissioners referenced the comparison charge that showed how other communities have handled affordable housing.

During Wednesday’s discussion at the Planning Commission on the Affordable Housing Ordinance, several of the commissioners referenced the comparison charge that showed how other communities have handled affordable housing.

The general consensus by the commissioners was that the previous 35 percent affordable housing policy was not feasible, and the only question was going to be whether the city could even make a 15 percent requirement work.

The conclusion by Plescia & Co. was: “Imposition of the existing City of Davis affordable housing ordinance requirements (either on-site BMR units or in-lieu fee) results in a negative residual land value for four of the indicated multi-family rental housing development prototypes (Downtown Core Mixed-Use, Student Housing, Large Traditional and Large Urban Mixed-Use), thereby increasing the infeasibility of multi-family rental development as the result of higher total development costs or lower rent associated with the affordable housing requirements.”

The community has tended to push back on what they have seen as the weakening of the Affordable Housing Ordinance to go from a 35 percent requirement to a 15 percent requirement. Some of that is understandable.

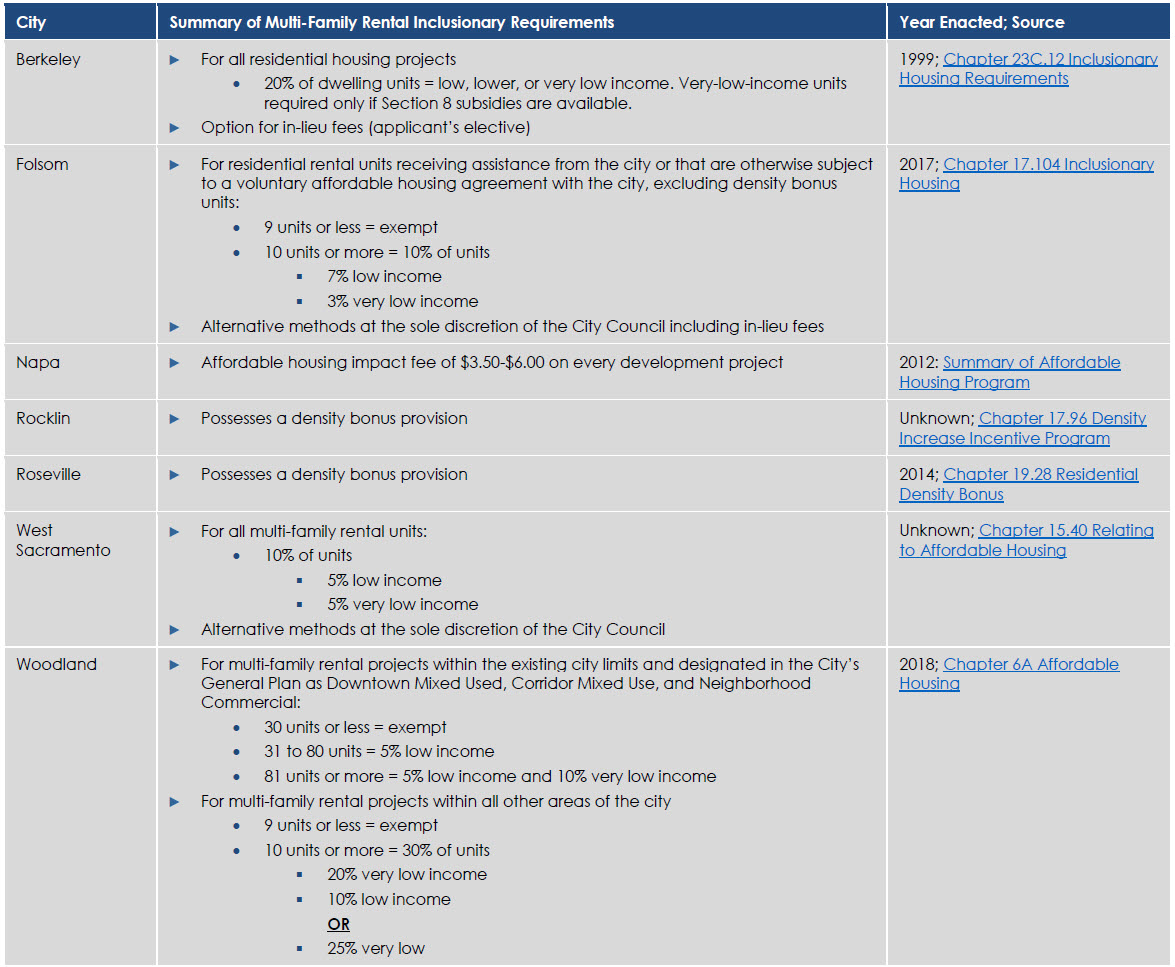

Looking at what other communities are doing is a good way to at least put the city of Davis’ situation in context.

There is a broad range of requirements for affordable housing. On the upper end, Berkeley requires 20 percent of dwelling units to be set aside for low, lower, or very low income. Woodland has a bifurcated system where, for larger projects in general, 5 percent are to be set aside for low income and 10 percent for very low income, but that includes only those within the existing city limits and designated in the General Plan as mixed use or neighborhood commercial. For others, the affordable requirement goes to 20 percent for very low and 10 percent for low, or 25 percent for very low.

That’s the highest requirement we see. The rest of the communities have much lower requirements. In Folsom it is a total of 10 percent. For Napa, there is an affordable housing impact fee of $3.50 to $6 on every development project. Rocklin and Roseville both have a density bonus provision. West Sacramento has a 10 percent requirement on rental units.

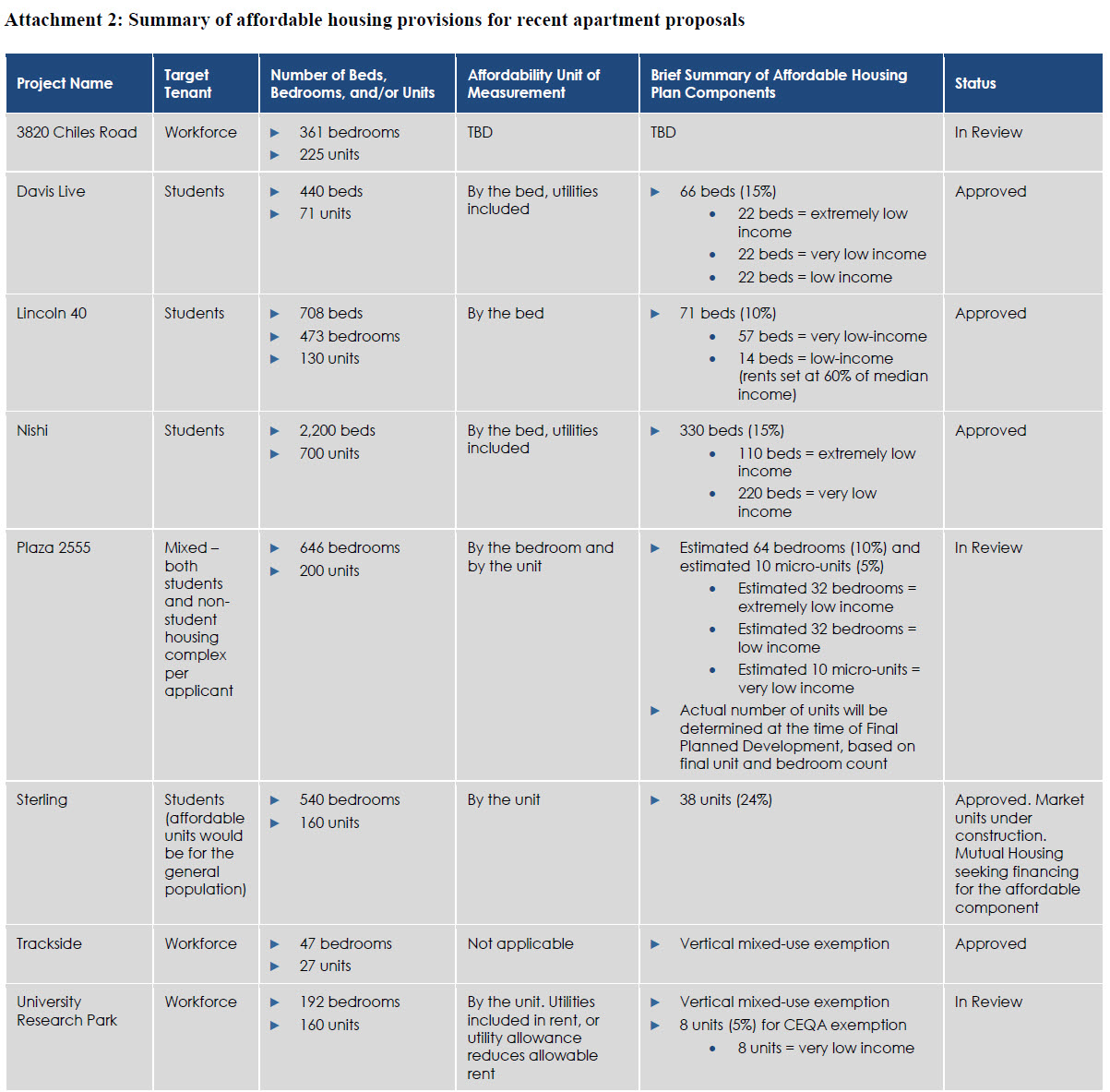

Looking at the recent apartment proposals in Davis, there is a wide variety. They have not determined the affordable provision for the Chiles Apartments. Davis Live has 15 percent of the beds set aside as affordable. Lincoln40 has 10 percent of the beds set aside. Nishi has 15 percent of the beds set aside.

Plaza 2555 will have affordability by the bedroom and the unit. The current estimate is 10 percent of the bedrooms and an additional 10 micro-units to get to the 15 percent requirement.

Sterling is one of the few doing it by the unit, and they have 38 of the 160 units. But Sterling is the only one of these with a land dedication site. In addition, the 38 units is a smaller fraction of the total number of the 540 bedrooms.

Trackside is exempt under the vertical mixed-use exemption. The University Research Park will also be exempt under the vertical mixed-use exemption.

Concluding Thoughts:

For months I have been hearing people demanding that we not water down our affordable housing ordinance, alarmed that we have reduced requirements to 15 percent. We have had the study now and the first discussion of the affordable housing ordinance, and I think it can only be described as “worse than we thought.”

The reality is that 35 percent is not coming back. The even worse reality is that 15 percent may not be viable either. Wednesday night’s discussion by the Planning Commission was less than  satisfying for a number of reasons, but it does seem that two things are clear.

satisfying for a number of reasons, but it does seem that two things are clear.

First, we are looking at a negative sum game, as Commissioner Herman Boschken put it, where we are pitting social equity against economic development and it is a lose-lose prospect. By that we mean, if we insist on a higher number of affordable units, there is going to be a trade off. That trade off might that we give up other costs. That trade off might be that we discourage the badly needed rental housing. There is no good answer in this respect.

Second, while some have noted that we have done 15 percent at recent projects, the reality, as David Robertson pointed out, is that it was only possible because of the by-the-bed factoring enabling it to be viable.

The only two exceptions to this in recent history are Sterling and West Davis Active Adult Community – both of which have land dedication sites.

That raises the troubling prospect that on future projects which are not student housing and available for bed rentals and do not have land dedication sites, we may have to go even lower to provide any affordable housing at all.

Moreover, we should keep in mind that the next wave of housing projects are likely to be mixed use and exempt. Although the commission pushed back slightly against the exemption on Wednesday, the economic reality there seems rather clear.

economic reality there seems rather clear.

A comparison chart to other communities that was distributed shows that most other communities are actually doing less than we are. No one is at 35 percent. Berkeley seems to get to 20 percent. Woodland is getting to perhaps 25 percent on some projects. But many are at 10 percent or only charged fees.

Among the public comments there still seems to be a disconnect, with some maintaining because we have done something it means we can still do something. The problem with that view is it fails to consider how we have been able to do something, and that is where the analysis by David Robertson was helpful. We were able to get to 15 percent because we able to put affordable beds together to create enough revenue for the developer to make it work. But the scale doesn’t work when it moves to by the unit.

I think we need to start thinking outside of the box, as people like Mary Jo Bryan have suggested. We need to look at funding strategies, and we need to look at a variety of alternatives including: parcel tax funding, lobbying for an increment tax renewal, and also considering the possibility of Measure R exemptions for high percentage affordable projects.

That may not be the answer we want, but it might be the only way to get to the solutions we need.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

For months we’ve had heavy debate over affordable housing policies until we actually get the ordinance come forward with analysis that shows that the slow growth naysayers were wrong all along and then suddenly it’s crickets.

Better to get cash from developers and use it to fix the roads. That benefits everyone rather than spend it subsidizing a few individuals.

There is not really anything to comment on here. David Greenwald provides his usual shallow “analysis” with selective quoting and ignoring the larger issues and context.

There’s a discussion to be had, but it’s been proven time and again that the Vanguard is not a reasonable venue to have it.

My very first spot-check of one of the jurisdictions in the comparison table showed it is wrong: Roseville has a 10% affordable housing policy in its General Plan/Housing Element. The table shown in this so-called “analysis” is haphazard and highly incomplete. It is not sufficient to serve as the basis for any kind of reasonable comparative analysis.

As far as the Plescia report, the Planning Commission already registered its unanimous displeasure. I would add that it is myopic in scope and doesn’t seek to provide the type of in-depth analysis that other communities do. As the Planning Commission stated, we must start with a detailed analysis of our needs. In concert with that, we should also look at (as even communities like Roseville have) the demand for affordable workforce housing that is created/induced by the construction of market rate housing.

Regardless, subsidized housing is a complete waste of money.

Would you care to explain why? I can see how many rightly should realize that subsidized housing means someone is paying for the subsidy… not clear what you meant by,

Suspect that those who have/benefit from SH feel one way, those paying for that subsidy, another… but just guessing, there…

BTW, there are other folk who receive ‘subsidies’… SS (and particularly SSI) recipients, and certain professions… and the minimum wage concept could be deemed a ‘subsidy’…

Really? If you’re goal is to make housing more affordable for some people, then it’s by definition not a complete waste of money. Fact is, affordable housing works for some people.