When the plaintiffs agreed to drop their litigation on January 18 – without prejudice, meaning they are free to re-file at a later point in time – it became the latest in a pattern. Since 2011, four ballot measures – the water project and three housing developments – had lawsuits filed in the middle of the election campaigns.

None of these suits have been successfully litigated – although the city did settle the water litigation in August 2014 despite having successfully litigated the water rates previously.

The litigation has become almost a standard part of efforts to defeat primarily housing developments. Ballot measures are not the only targets – in the last few years we have seen three lawsuits against the approved hotels (Hotel Conference Center, Marriott, and the Hyatt House), which have all been settled.

There is outstanding litigation against both Lincoln40 (expected to go to court on February 8) and Trackside.

For good measure, Michael Harrington even sued his neighbor over a conditional use permit (CUP) for a therapist office – that went to court and then appellate court, with Mr. Harrington losing on both.

Four Ballot Measures Challenged Through Litigation

In 2013, the city placed the new water project on ballot for the voters to approve, which they did by a 54-46 margin on March 5, 2013. However, in the middle of the campaign, on January 15, Michael Harrington on behalf of YRAPUS (Yolo Ratepayers for Affordable Public Utility Services) and Nancy and Don Price filed a lawsuit against the rates.

The suit argued that the approved water rates “do not comply with Proposition 218 and are unconstitutional and illegal in that, inter alia, they impose a fee or charge incidental to property ownership which exceeds the proportional cost of the services attributable to the parcel.”

In early 2014, Judge Dan Maguire upheld the constitutionality of the city’s newly implemented water rates, writing, “Having considered all of the evidence and legal arguments provided by the parties, the Court finds that the water and sewer rates adopted by the City of Davis meet the proportionality standards of the California Constitution, and therefore the plaintiffs’ claims are denied.”

However, because the plaintiffs appealed the ruling and the litigation prevented the city from getting financing on great terms, they decided in August to settle the suit.

“The general terms of the settlement are that the plaintiffs will not oppose the city’s proposed water rates as set out in the current Prop 218 notice, that they will dismiss their entire case against the city, and that they will not file another case related to the water rates, the sewer rates, Measure I or do any other public process regarding these water rates,” City Attorney Harriet Steiner announced.

The city agreed to pay water and sewer charges at the same rate as everyone else and paid $195,000 to the plaintiffs for litigation fees.

While that arrangement saved the city money short-term, the city and council came to regret the agreement and have opposed settling lawsuits ever since.

In the spring of 2016, with Nishi on the ballot, Michael Harrington filed another lawsuit on March 18, 2016, on behalf a group called Alliance for Responsible Planning. They challenged the city’s approval of the traffic study, and charged that the city was in violation of their own affordable housing ordinance.

Judge Samuel McAdam denied this claim in August 2017 despite the fact that the ballot measure had failed by about 700 votes.

Judge McAdam wrote, “Petitioner fails to demonstrate that there is not sufficient evidence in the record to justify the public agency’s action, and therefore this argument does not support a finding that CEQA was violated.”

The judge ruled on the second part: “It is unclear what petitioner is arguing as the traffic study in the EIR does not assert that ’20 percent of the employed residents in those 298 non-student dwelling units would be employed in the Project’s R&D-office component.’ This argument lacks merit.”

The judge also denied the claim for a violation of the Affordable Housing Ordinance (AHO) after the plaintiffs conceded that in the case of Palmer v. City of Los Angeles from 2009, the court held that the Costa-Hawkins Act “precludes local governments from requiring a developer to set affordable rental levels in private rental housing units…”

Mr. Harrington dropped the appeal.

The two most recent occurred this year with Susan Rainier filing a lawsuit against Nishi on March 9, 2018, and Samuel Ignacio filing a federal civil rights lawsuit against the West Davis Active Adult Community (WDAAC) in September 2018.

Impact of Litigation and Integration of Lawsuits into the Campaign

While Nishi circa 2018 remains active, three of the four lawsuits filed during the election ultimately failed. There is quite a bit of caveat to that.

The water rates challenge failed in court as Judge Maguire ruled against it but, facing the potentially loss of financing, the city agreed to settle in August 2014.

The litigation against Nishi circa 2016 was defeated in court, even though the ballot measure had been defeated more than a year prior.

The litigation against WDAAC was dismissed by the plaintiff, as the plaintiff’s attorney agreed that the litigation was premature. It is conceivable, therefore, that the litigation could be revisited when the Davis-Based Buyers Program is finalized and there are building permits.

The impact of the litigation on the outcome of the elections seems to be pretty limited. Three of the four projects passed – by healthy margins of at least 9 percentage points.

The fourth went down to narrow defeat – Nishi in 2016. It is hard to know if the litigation itself made a material difference. The two issues that we have generally come to believe led to the narrow defeat were affordable housing and traffic – the two issues that the litigation focused on.

The causal impact of the two is harder to decipher. It is not clear that the litigation itself was a focal point of the opposition campaign in 2016.

The litigation was part of the central campaign in 2013, however.

In a letter dated January 15, 2013, to the city, Nancy and Don Price write, “We believe that the current rate system, adopted in 2010, and the new proposed structure, unfairly charge some classes of users differently than others, are terribly confusing and, for the many reasons outlined in the documents submitted to the Water Advisory Commission, city files, and the City Council, the current and proposed rates otherwise do not conform to law.”

The litigation was also a key part of the opposition campaign in 2018, even though the opposition have denied involvement in the lawsuit.

Alan Pryor, treasurer for the campaign against WDAAC, spoke before city council and noted that Attorney Mark Merin was caught in traffic.

Mr. Pryor stated that Mr. Merin, a very prominent civil rights attorney, filed a federal lawsuit against the city of Davis and David Taormino, the developer. “This lawsuit alleges that the proposed restrictive West Davis Active Community on the city of Davis on the November 6 ballot, which advertises its purpose as a planned community, taking care of our own, is being challenged in federal court, because it will perpetuate racial imbalance and discriminate against minorities by restricting sales to people in Davis or have a connection to people in Davis.”

Mr. Pryor and Rik Keller referenced the lawsuit during the forum on Measure L in October. In his opening remarks, Mr. Pryor said: “The taking care of our own, Davis-Based Buyers Program exacerbates all these demographic imbalances in Davis – which is why the developer and the city are being sued for civil rights violations under the Fair Housing Act by famed civil rights attorney Mark Merin.”

Mr. Keller, talking about discriminatory housing in Davis during one of his answers, stated: “A lawsuit has been filed alleging discrimination and Fair Housing violations by one of the most prominent civil rights attorneys in Northern California.”

Notice the importance attached not only to the lawsuit but the perceived prominence of Mark Merin – in all three comments.

Costs

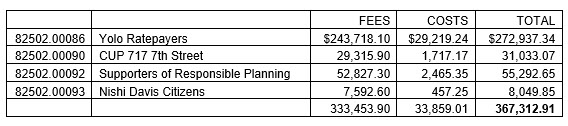

In October of 2016, the Vanguard filed a public records request to determine the cost of the litigation the city paid in which Mr. Harrington was either an attorney for or a party to the litigation. The city interpreted this to mean attorneys’ fees and legal costs the city paid.

At that time, it covered four lawsuits: the water rates suit, the CUP suit, the suit against Nishi, and the suit against the Hotel Conference Center project.

The hotel conference center would settle shortly thereafter, but the Nishi suit would go on for nearly another year.

In both the Hotel Conference Center and the Nishi, the city would be reimbursed costs.

A source familiar with the costs for Nishi estimates that by the end of this current litigation, it will cost the developers about $250,000 in fees and costs – assuming that Nishi prevails and is able to recoup their attorney fees. This is $250,000 in cash, out of pocket, up front.

While this is tiny relative to the overall cost of the project, the bigger cost is the delays from the litigation and increasing interest rates and construction costs.

Additional Costs – the Lincoln40 Factor

Fees and attorney costs are not the only metric of costs. For instance, the city undertook an EIR on Lincoln40 even though the project was exempt, in order to avoid potential litigation – it didn’t work, it was litigated anyway.

The Vanguard in March 2018 reported on the comments of then-Mayor Robb Davis.

“I will acknowledge a little bit of frustration as I read (the EIR), realizing that we didn’t have to do it,” he said. “We chose to make a disclosure when the law of the state of California would not require it.”

The mayor explained, “I think that gets to this council’s willingness to be transparent and staff’s desire to be transparent. I think those are important qualities but they do add costs that mean that we can’t do other things.”

He said, “I think we need to consider the burden that we place on any project and what it means. It bothered me a little bit over the weekend.

“As a disclosure document it’s something that we can be proud of,” he added. “But does it really serve our community when we’re not required to – and it adds costs that otherwise could be going into a few extra beds.”

As Mayor Davis pointed out, without those added costs, maybe they could have pushed for the developers to cover more of the overcrossing – if the developer didn’t have to pay for the EIR, maybe they could have taken on another half to a full million extra dollars for the overcrossing.

On the other hand, maybe they could have pushed the developers to go up to 100 affordable beds rather than 71.

That is 29 students every year that will not have the opportunity for the reduced rate of affordable units, because someone might have sued the city and the city went the EIR route when they didn’t have to.

Davis City Manager Mike Webb explained the impact of litigation on city planning efforts was that the city has a tendency to undertake the most conservative or “iron clad” approach to CEQA documentation.

“This does not necessarily result in the analysis itself or the conclusions being any different, but it is packaged in a way that affords the greatest level of defensibility from a legal perspective,” he explained, stating that this could mean “preparing an EIR instead of a Negative Declaration.”

There is a cost to this, however, he explained. “The higher level documents almost universally require more time and expense to prepare – sometimes considerably more. The monetary expenses are borne by the applicant,” he said.

At the same time, “The applicant, staff, city commissions, Council, and community all share in the additional time needed to prepare and review these documents. One could argue this is time well spent. Another could argue there are opportunity costs to this time.”

Furthermore, “Although the State has created more ‘streamlined’ avenues of CEQA documentation, we often find applicants wanting to forego the streamlined path, at their own time and expense, in order to have a CEQA document that is more ‘tried and true’ and familiar to the courts. We now see project applicants setting aside funds from the onset in anticipation of litigation – funds that they may well prefer to invest in the project or into a Development Agreement.”

And this, he said, does not include another cost, as the unknown in this is “what projects we never see because of the costs and the risk aversion applicants may have to litigation. “

Concluding Thoughts

The striking conclusion here is how little the litigants actually gained from their actions. In any sense of the word.

Four projects here – three of them were approved by the voters regardless of the litigation. It is not clear that the fourth project was defeated due to the litigation either.

Only on the water project did the litigant get anything – just under $200,000 in attorney fees. Both the water project and Nishi’s plaintiffs lost in court, WDAAC dismissed their case, and the fourth is still pending – but we see no reason to believe that the plaintiffs will prevail there anyway.

In summary, my conclusion is that litigation does not work. It did not succeed in gaining settlements after the first one. It did not succeed in front of a judge. And, for the most part, it did not help the opposition succeed at the ballot box.

So long as the city takes the position that they will fully litigate every single lawsuit and the developers adhere to that, there is no reason for anyone to litigate.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

David Greenwald said . . . “The striking conclusion here is how little the litigants actually gained from their actions. In any sense of the word.”

If Keith O were here he would be saying, “No, the striking conclusion here is how little the Vanguard readers actually gain from reading this republishing of the same tired narrative. In any sense of the word.”

Well channeled KO, MW.

Did the City not collect payment from the litigants after losing their lawsuits? You know that they would have collected from the City if they had won.

I reported this:

“In both the Hotel Conference Center and the Nishi, the city would be reimbursed costs.

A source familiar with the costs for Nishi estimates that by the end of this current litigation, it will cost the developers about $250,000 in fees and costs – assuming that Nishi prevails and is able to recoup their attorney fees. This is $250,000 in cash, out of pocket, up front.

While this is tiny relative to the overall cost of the project, the bigger cost is the delays from the litigation and increasing interest rates and construction costs.”

Seriously? That’s quite an over generalization. Good thing the Vanguard wasn’t around during the early civil rights movement. Otherwise, activists would have given up after Dred Scott v. Sanford and Plessy v. Ferguson and there would never have been a Brown v. Board of Education. Even in the narrow context here, the fact that a small number of cases may have been ill-conceived or poorly timed, does not warrant such a sweeping conclusion.

My comment was meant to be more narrow than that.

I agree with Eric, and would add Loving v. Virginia.

TDHCA v. Inclusive Communities, Inc. (2015)

And the following two of many local cases that weren’t decided in the courts, but were resolved due to legal actions and investigations:

http://www.fairhousingnc.org/2014/city-of-dubuque-to-end-discriminatory-residency-preference-in-housing-program/

If your underlying goal is to oppose change, then anything that slows down the rate of change is a benefit. Given the rate of development in Davis over the past two decades it is reasonable to conclude that those opposed to change have been quite successful using Measure J/R and litigation to drive up the costs and risks for new development. If you were an existing property owner/landlord in 2000 then you have done quite well over the period of time since via the increases in your property values and rents.

Why the repeated references to the civil rights attorney in the WDAAC case?

David Greenwald [on 9/29/2018 about WDAAC’s “Taking Care Of Our Own” program]: “I agree with you, that the Buyer’s club is not going to pass legal muster…”

Jason Taormino [WDAAC developer, 10/9/2017]: “…we all recognize that the legality of discriminating based upon zip code is questionable…”