By Rory Fleming

The National District Attorneys Association is the main professional body for American prosecutors, and like the Fraternal Order of Police, it is retrograde when it comes to justice. The organization has fear-mongered about youth use of marijuana skyrocketing in states that have legalized the substance, while pushing for heightened federal crackdowns. The NDAA also aggressively fought a White House report that sharply criticized the use of bogus forensic evidence in criminal courts.

In short, the NDAA is not a particularly meritorious organization, and amplifies entrenched ways of law enforcement thinking. One of its vehicles for doing so is its magazine, aptly titled The Prosecutor. Generally speaking, to read it, one must be a member of the organization, and membership is only open to “those working in the prosecution field, as well as individuals seeking justice for communities and working on behalf of victims.”

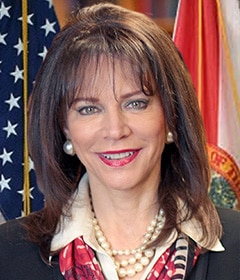

But thanks to someone posting it online, the general public gets to see Miami-Dade County State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle, one of the most conservative top prosecutors under the Democratic Party banner, prop herself up as a progressive.

In a new 16-page article, Rundle explains her approach, which she dubs “Miami-Style Smart Justice.” In the written equivalent of a side-eye, Rundle writes, “While more and more district attorneys have begun to experiment with what some call ‘progressive’ solutions, strategic remedial measures that reduce crime, improve lives, and save money are a matter of tradition in Miami-Dade County.”

That is certainly one way to put it.

The average person won’t know the history of Rundle’s tenure, but it’s well worth exploring as an illustration of the glaring gap between a quasi-reformist prosecutor’s rhetoric and the realities on the ground. (And while this is about Rundle, it could just as easily be about the district attorneys of places like Brooklyn, Manhattan, and other liberal urban jurisdictions not impacted by the Soros-funded wave of progressive DAs.)

The Good

In her article, Rundle sets herself aside from what she deems the “Traditional Approach” of US criminal justice: essentially, lock ‘em all up. That may be truer now than it was in the past. Prison admissions have indeed gone down in Miami-Dade County over the years, thanks in part due to changes Rundle has made In FY 2000-2001, Miami-Dade County accounted for 9.1 percent of the state’s annual prison admissions, but by FY 2015-2016, it accounted for only 6.8 percent—beaten out by both Hillsborough and Broward Counties. Perhaps a change of heart came sometime after 2007, when Rundle still bragged on her government website about ratcheting up the harshness of punishments, using the same criminal code that she herself helped draft.

Rundle has also consulted with some criminal justice reform groups on ways to enact incrementalist reforms in recent years. The Justice Collaborative, the successor organization to a Harvard project that excoriated Rundle’s record on the death penalty in 2016, helped her create a modernized bail policy, by which people facing some nonviolent misdemeanor charges—including prostitution and “driving with license suspended for failure to pay or appear”—are recommended for release from pretrial jailing without payment. The extent of impact is unclear, though Rundle has started taking donations from the bail bonds industry this campaign cycle.

It is also worth acknowledging that whatever good came out of the new bail policy would likely be negated by a new $393 million “megajail” the mayor and county commission are looking to build. Reflecting her comfort with mass incarceration, Rundle has not expressed her opposition to the plan. In contrast, Rundle’s 2020 challenger, Melba Pearson, has.

The Bad

Like other quasi-progressives, Rundle implemented many “reforms” that broadened the criminal justice system’s iron grip on vulnerable, non-dangerous people’s lives. Rundle is a major supporter of the county’s drug court,  which was the first in the nation. While drug courts are better than prosecutors simply trying to send all people who use drugs into jails and prisons, they are only marginally so. Compliance is highly difficult. The courts criminalize relapse, even though returning to drug use is part of many people’s path to recovery from addiction.

which was the first in the nation. While drug courts are better than prosecutors simply trying to send all people who use drugs into jails and prisons, they are only marginally so. Compliance is highly difficult. The courts criminalize relapse, even though returning to drug use is part of many people’s path to recovery from addiction.

In Delaware County, Pennsylvania, more people died of overdose in 2017 alone than succeeded in the drug court from 2008 to 2018.

Actually treating drug use as a public health issue means removing the matter from the criminal justice system entirely, so health professionals, and not lawyers and judges, can make the right diagnostic calls. Rundle does not get this, or she chooses not to get it, privileging a rigid and simplistic criminological analysis over the ethical practice of medicine.

In her article, Rundle justifies her approach by pointing to recidivism statistics—68 percent of released prisoners are rearrested at least once within the first three years after release, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Rundle then conflates drug and alcohol use with crime by mistaking correlation with causation, remarking that one study found that “over 84% of state prisoners were alcohol or drug involved”— whatever that means. This is a widely believed point of view amongst American law enforcement, but not one that a supposedly progressive prosecutor should parrot.

Rundle cannot honestly rest her hat on her fidelity to victims’ rights, either. Twelve years into her tenure as State Attorney, Rundle’s office had no specialized sex crimes unit. Rundle still does not seem to have one today, though she has one for domestic violence. For decades, Rundle had done next to nothing to mitigate the non-testing of over 10,000 rape kits. She waited for other governmental actors to push the issue, unlike some of her peers in other big, liberal cities.

Rundle also virtually never prosecutes police shootings of unarmed civilians. Having worked on many prosecutor campaigns across the country, I can say that this decision often has most to do with political cowardice. The police, the hardest law enforcement sector to change, explode at DAs who charge errant cops, and channel their anger into political retaliation. Regardless of personal motives that might include self-preservation, prosecutors like Rundle nuke the criminal justice system’s legitimacy every time they fail to charge an appropriate case. That is doubly true in communities of color, where people are much more likely to be killed by cops.

The Ugly

From a human rights standpoint, earlier parts of Rundle’s tenure were nothing short of heinous. Rundle charged kids as young as 13 as adults; one of her long-term deputies once seriously considered a murder charge against a 5-year-old. From 2006 to 2015, Miami-Dade County had handed down 13 juvenile life sentences without parole—two more than Harris County, Texas (Houston), despite Harris County having almost double Miami-Dade’s population.

Rundle’s administration also obtained more death sentences from 2010 to 2015 than 99 percent of district attorneys across the country, with some tossed out for deliberate, purposeless prosecutorial misconduct. Her own assistant prosecutor, Abraham Laeser, broke national records by obtaining over 30 death sentences himself (many of which were sought after he got caught unzipping his fly in front of a defense attorney and a female jury consultant).

Today, Rundle holds the state of Florida back on big policy debates. As the longest-serving registered Democrat in the highly influential Florida Prosecuting Attorneys Association, she has major sway over how other Florida state attorneys perceive bold reforms (like no longer seeking the death penalty) from progressive prosecutors like Orlando State Attorney Aramis Ayala. Instead of sticking up for Ayala, Rundle chose to denounce Ayala along with the rest of the State Attorneys. Elsewhere, Rundle has defended ugly practices like Florida’s direct-filing of kids to adult court via prosecutorial whim, which helps make her state the nation’s cruelest on juvenile justice.

This is not to say that Rundle does not still make awful calls in her main role as prosecutor. Darren Rainey’s death immediately comes to mind. Rainey was a middle-aged Black man suffering from schizophrenia, serving two years in a Miami prison for cocaine possession. When three guards threw him into a scalding hot shower, his skin sloughed off and he was effectively boiled alive. To Rundle, this constituted no crime, and she refused to charge them.

In her NDAA article, Rundle claims to be ahead of the curve on treating people with mental illness with dignity in the criminal justice system. But her handling of Rainey’s case led to Rundle’s political party calling for her resignation. And after Rundle traveled to New York City to be on a mental health-focused panel at John Jay College’s national “Smart on Crime” conference, Ed Chung at the Center of American Progress personally apologized for Rundle’s attendance on Twitter.

Her poor discretion is not limited to one standout case. In 2015, Rundle sought a charge with a three-year mandatory prison sentence for marijuana. This was not a giant retailer of the plant, either. The defendant, a Black Hispanic man named Ricardo Varona who grew 15 marijuana plants in his home, argued that he did so to help his cancer-stricken wife with pain.

Varona’s race matters because the ACLU of Florida recently reported on the extreme racial bias found in Rundle’s administration of “justice.” Black neighborhoods in her area face higher arrest rates. The charges at arrest, which police set in Florida, are harsher for Black people, who also face the most drug charges. But the inequality is not limited to the cops. Rundle’s office gets to decide whether to change the charge set by police.

Ultimately, the ACLU unveiled that “Black Hispanic defendants are convicted at a rate that is over five and half times higher than their share of the county population.” In addition, “Black Hispanic defendants serve jail or prison sentences at a rate over six times greater than their share of the county population,” and Black people who do not identify as Hispanic get the harshest sentences in Miami-Dade on average.

Katherine Fernandez Rundle neglects to address the egregious ways she stands on an island all her own compared with prosecutors in other big, liberal cities. The fact that some criminal justice reform organizations cooperate with her in a limited capacity is not a signal that she is “progressive,” but more a recognition that cooperation is for the greater good of a jurisdiction with approximately three million residents.

Given Rundle’s electoral popularity, it is a shame that Miami-Dade may not soon see the sweeping change a true progressive prosecutor candidate, like Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner, can bring.

On the bright side, Miami’s elected prosecutor turns 70 this year, meaning that a change in guard in the somewhat-near future is inevitable. Time is running out for Rundle to demonstrate that her self-rebranding exercise in The Prosecutor contains the merest shred of truth.

This article was originally published by Filter, a magazine covering drug use, drug policy and human rights. Follow Filter on Facebook or T

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9