Is Justice Even Possible 44 Years Later?

Innocent until proven guilty. That’s the hallmark of our justice system. But what happens when justice becomes injustice and the innocent become wrongly convicted?

Contrary to what you learn in school, our system of “justice” has been set up for guilty people. As long as the accused is guilty and is punished appropriately, the system works—sort of all right. But if the person is innocent, and they don’t have the resources or happen to live in a community that provides them with competent legal counsel, it starts to become a problem.

Once you are convicted of a crime, the system is ill-equipped to deal with the consequences. The presumption of innocence—always sketchy—completely shifts. Once convicted, you are guilty until proven innocent.

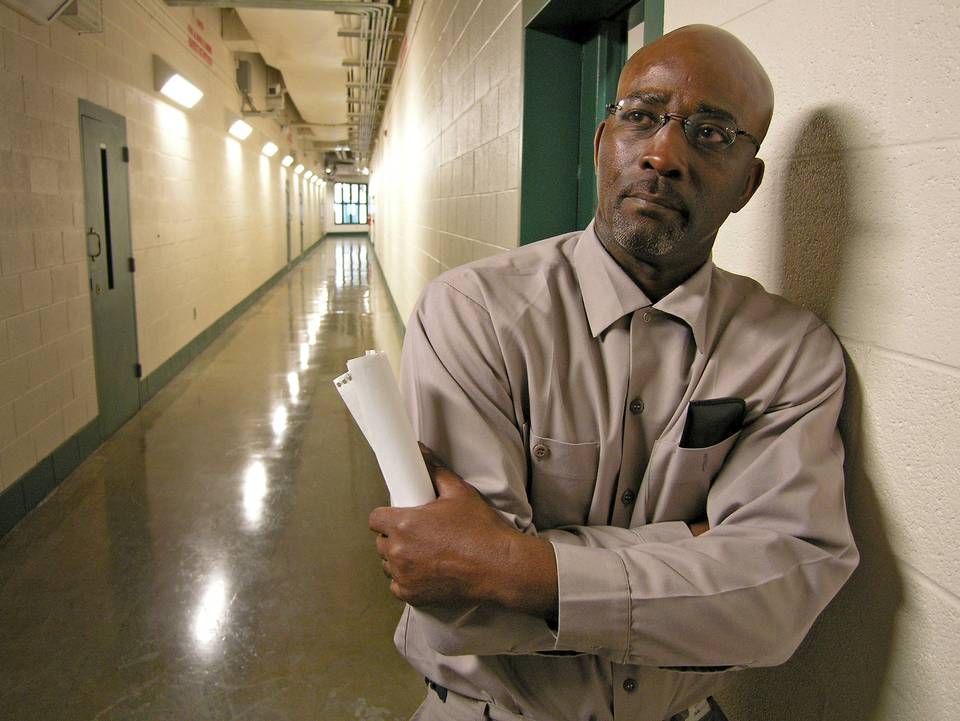

That’s what Ronnie Long faces. Forty-four years later. On charges that frankly should not have merited that long a sentence to begin with. Never mind that the eyewitness identification was flawed—to put it mildly. Never mind that the police withheld exculpatory evidence. Never mind that he was tried in 1976 in North Carolina, the south, before an all-white jury and he is a black man accused of raping a white woman.

All of this can be explained away. Every bit.

That’s what state’s attorney Phillip Rubin wants you to believe and, more importantly, argued before a panel of 15 judges on Thursday.

He argued that any error was harmless and would not have resulted in a different verdict.

Withheld evidence? That was “sloppy,” Rubin acknowledged. He disagreed that it was intentionally withheld. He disagreed that it was material to the case.

From his perspective, he said, “All of the evidence in this case is consistent with his guilt. I would take a very different view of this case if it wasn’t.”

He added, “There is nothing shown that actually exonerates Mr. Long.”

But is that true? After all, they found a ton of hairs and a ton of fingerprints at the scene—none of which matched Ronnie Long. Evidence was withheld—to me that exonerates Long. Poor eyewitness identification.

Maybe we should ask if there is any thing that actually incriminates Ronnie Long? If they held a trial now with what they know, could he be convicted?

This is the problem. A man has been sent to prison for 44 years and the only way we can get him out is to basically prove him innocent 44 years after the fact. But should that be the standard at all? Have we set the bar too high for freedom and for proving mistakes—after mistakes were clearly made 44 years ago?

It’s a high bar to begin with. That bar is higher because the hearing was in front of an en banc panel. That means all 15 judges on the circuit. That means they have to convince eight of them to give this man a new trial.

The good news is that several of the justice clearly saw the injustice here.

Judge James Wynn said, “Liberty means something—you don’t just take away a person’s freedom it means something.”

This was an all-white jury in 1976 in North Carolina. Judge Wynn grew up in Concord, North Carolina, where this case occurred and knows the history. He said, “There were black men being prosecuted wrongfully and, we know, in great numbers.”

“He spent 44 years in jail. Even if he were to get out, that’s a significant punishment. I just don’t understand why we wouldn’t take a look at it.”

Judge Keenan said, “Please don’t ignore what I see to be the elephant in the room here, Detective Isenhour lied on the stand, he did perjure himself.”

Judge Stephanie Thacker, perhaps the reason this case got to the full panel of judges because of her dissent from a three-judge panel ruling in January, pointed to the lack of physical evidence on the  jacket, or the toboggan, or the gloves, or the paint, or the fibers, and to the 43 fingerprints. She asked, “What if the jury would have heard that?”

jacket, or the toboggan, or the gloves, or the paint, or the fibers, and to the 43 fingerprints. She asked, “What if the jury would have heard that?”

Judge Robert King said, “The testimony was incorrect. Is that right?”

Rubin said, “I would agree with that. Yes, your Honor.”

To me the most telling exchange came at the end between Chief Judge Roger Gregory and the state’s attorney Phillip Rubin.

“You talk about there’s no chance… that this would have made a difference,” he said. But he pointed out that during the trial the prosecutor said that not only is the victim’s testimony accurate, “but totally consistent with every piece of physical evidence existed—that’s what the prosecutors told the jury. That was not true.”

When he started to dither, the Chief Judge pressed with “that’s a yes or no answer.”

He acknowledged, “Your honor I don’t think that was fully accurate, but if I may explain…”

“The answer is no it wasn’t,” Judge Gregory said. “We’re talking about justice and looking back some 44 years.” He walked through the evidence withheld and the inconsistencies. “Isn’t that appalling to justice?”

Rubin responded, “I don’t think so because I can put it in context for you.” He said, “All of the evidence in this case is consistent with his guilt. I would take a very different view of this case if it wasn’t.”

He added, “There is nothing shown that actually exonerates Mr. Long.”

This is the problem that we face in a microcosm. Questionable identification, lack of physical evidence, and the investigator either lied or whatever Mr. Rubin said—I’m not sure how what he said actually soften the blow.

After listening to this hearing I will say this: this is not justice. Ronnie Long will never get justice here. He has been robbed of 44 years by an all-white jury and a dishonest police officer and the system has limited to no ways to correct it.

We need to change the way we look at wrongful convictions and figure out something better. I hope the court does the right thing, but this system is broken.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9