By Julietta Bisharyan and Nick Gardner

Incarcerated Narratives

BLYTHE, CA –– On May 15, 2020, Chuckawalla Valley State Prison (CVSP) confirmed its first two cases of coronavirus. A month later, the prison reported 989 cases.

Despite months of warnings and implementations of preventative measures, the prison had tested only 16 people in a building that housed 200.

Timothy Casarez, who is currently incarcerated at CVSP, shared his experiences with the Davis Vanguard, after witnessing the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR) neglect during the pandemic.

In the beginning, Casarez said that prison officials quarantined the building with a strip of caution tape to keep those infected from the untested population, who were assumed to be healthy despite showing symptoms.

Due to overcrowding, there were no available phones on both sides, which forced infected individuals to swap phones with those presumed to be healthy.

No cleaning or sanitizing occurred during the switch. The uninfected individuals, who slept just three feet away from those positive with the virus, were neither tested nor quarantined.

Those considered healthy and referred to as “negatives,” were moved to other yards, spreading the virus further at the prison. Once they were tested positive, they returned, with some even coming back to the quarantine zone the very next day.

“I’ve been in prison 12 years and never once have I seen so many people moved in so little time,” Casarez says.

On May 23, Casarez was tested for the virus along with seven others in his area. While their test results were pending, they experienced COVID-19 symptoms, including dizziness, headaches and a sore throat.

The next day, they were told that they would be moving to a different yard, as their bunks were needed for the sick population. Casarez asked to speak with the correctional lieutenant and told him that his entire area was sick and had tests pending that were certain to come out positive

“We received the same answer that time: ‘They told us to move you. We have to move you.’ I never found out who ‘they’ were,” adds Casarez.

When all seemed to be at a loss, Casarez decided to refuse movement and filed a grievance. He called his family and friends and told the four officers that he was not going to move. Three other incarcerated persons joined him in his protest.

“To me, it was a thing of conscience. I was not going to knowingly jeopardize other people’s health.”

In all of his years of incarceration, Casarez says he has never received a disciplinary write-up and has always done everything the institution has asked him to do, including non-voluntary transfers. That day, however, he put everything on the line to avoid being moved elsewhere.

“I thank God that one lieutenant heard me out as a person rather than as an inmate, and he kept me in the building.”

The others who were sent to the uninfected yards returned the very next day having tested positive.

Eventually, a test was ordered for every person in the prison, but at that point, about a thousand cases were active, over an area covering less than a square mile.

Since the major outbreak has begun to subside, no major follow-up tests have been performed on the population. Casarez says he still feels symptoms of the virus to this day.

“I fear when the next virus comes to Chuckuwalla, it will follow the same playbook. And once again, it will require a convicted felon to correct the people you pay to keep society safe.”

Regarding accountability, Casarez observes a blame game between those in charge of medical and the officers. He believes that all were involved in the failures of handling the pandemic at CVSP. Should blame continue to be passed, says Casarez, nothing will change.

“When compared to other prisons, CVSP is doing well. But when I mess up, I’m corrected. I accept that. Every good citizen should. Why should the state be any different?”

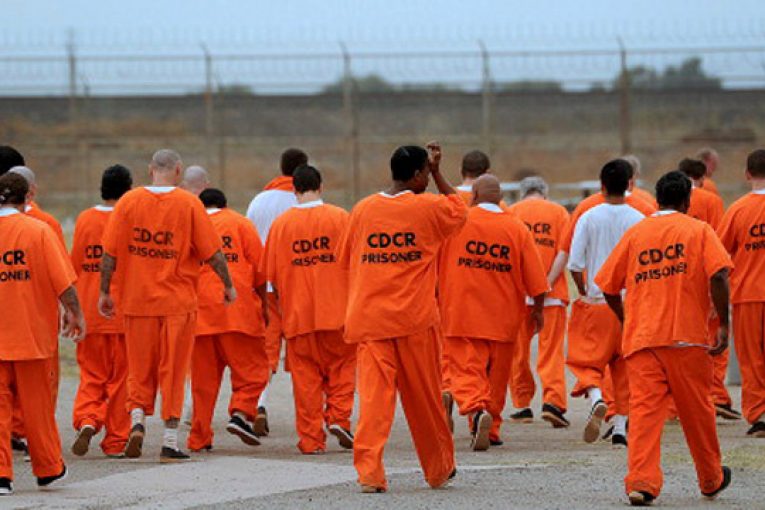

CDCR Confirmed COVID-19 Cases and Outcomes

As of Oct. 30, there are a total of 15,825 confirmed COVID-19 cases in the CDCR system – 539 of them emerged in the last two weeks. 3.8 percent of the cases are active in custody while 2.8 percent have been released while active. Roughly 93 percent of confirmed cases have been resolved.

There have been 78 deaths within the CDCR facilities. 15 incarcerated persons are currently receiving medical care at outside health care facilities across the state.

On Oct. 26, an incarcerated person from California Institution for Men (CIM) died at an outside hospital from what appears to be complications related to COVID-19. This is the 26th incarcerated person at CIM to be identified as a COVID-related death.

On Oct. 28, CDCR reported that another incarcerated person from Chuckawalla Valley State Prison (CVSP) died, marking the 78th incarcerated person death related to COVID-19.

CDCR officials have withheld the individuals’ identities, citing medical privacy issues.

A recent increase in the number of the COVID-19 cases at the California Institution for Men (CIM) has led to prison officials taking extra steps to help mitigate the spread of the virus by moving medically vulnerable incarcerated persons and continually requiring the use of face coverings.

“CDCR (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation) takes the health and safety of those who live and work in our state prisons very seriously,” CDCR press secretary Dana Simas said. “CIM is taking extraordinary steps to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, including moving inmates identified as medically vulnerable for COVID-19 complications from open-dorm settings to celled housing, staggering recreation, showers and dining in cohorts, and continuing to require facial barriers be worn by all staff and incarcerated persons.”

The steps include enforcing the wearing of face coverings, social distancing directives, providing incarcerated persons and staff with personal protective equipment, having isolation and quarantine space available, contract tracing for both inmates and staff and continued testing of previously-positive incarcerated persons even after their case is resolved.

Simas also noted that staff are tested bi-monthly and weekly when an outbreak is reported. Incarcerated persons and staff are required to wear face coverings.

As of Oct. 30, CIM has 27 active cases, with 12 new cases in the last two weeks.

On Oct. 29, Pelican Bay State Prison (PBSP) had its first inmate case of COVID-19, confirmed by CDCR.

According to CDCR spokesperson Terri Hardy, officials followed protocols governing the movement of CDCR patients, which includes implementing a 14-day quarantine for incarcerated individuals that have left the facility, screening and testing them multiple times during that period.

“PBSP has designated housing areas for both isolation and quarantine, as approved by the court-appointed Federal Receiver,” said Hardy.

Deuel Vocational Institution (DVI) is now the only prison left with zero confirmed cases.

In the past two weeks, Valley State Prison (VSP) has tested the most, 85 percent of its population. CA State Prison, Solano has tested the least, just 5 percent of its population.

There are currently 97,690 incarcerated persons in California’s prisons – a reduction of 24,719 since March 2020, when the prison outbreaks first began.

Effect on the Public

A recent watchdog report has concluded that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) failed to abide by basic safety protocol in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG), responsible for monitoring conditions throughout the state prison system, has been conducting reports into safety standards and mitigation practices at the CDCR’s 54 facilities.

An OIG report released this week highlighted how in June, amidst a spike of coronavirus cases in California prisons, the CDCR relaxed face-covering protocol to allow incarcerated individuals and staff to remove masks when six feet from another person— a practice determined by the report to have “increase[d] the risk of COVID-19’s spread among the staff and incarcerated population” at CDCR facilities.

This report comes as part of California State Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon’s request for the OIG to monitor COVID in state prisons. The first report, which was released in August, focused on COVID-19 screening practices.

Despite the fact that the CDCR had purchased an adequate amount of masks for both staff and incarcerated individuals, the report found that mask mandates were rarely enforced by supervisors. OIG investigators reported routinely seeing individuals without masks or those with masks using them improperly. A visit to North Kern State Prison immediately following the death of an employee found that “a significant number of staff members seemed cavalier about the threat of the virus and displayed that attitude by failing to adhere to the face covering policy.”

The OIG is urging that CDCR officials clearly outline safety policy and impose disciplinary action on those not in compliance. In response to the report, CDCR secretary Kathleen Allison pledged the department’s commitment to “clearly communicate the importance of adhering to physical distancing and face covering protocol” and “consistently enforce those policies and procedures.”

In 2011, Jordan Jackson was sentenced to 35 years in California State Prison, Sacramento for beating and severely injuring his infant son. According to Cheryl Canson, Jackson’s mother, Jackson suffers from bipolar disorder— a condition worsened by the fear and anxiety of a deadly disease spreading in close quarters.

According to Canson, incarcerated individuals are not informed of those who have tested positive for COVID-19. This confusion, coupled with the trauma of being incarcerated, is what Canson believes to escalate mental health symptoms in people such as her son.

CDCR is continuing to pursue mitigation strategies such as closing facilities, testing employees regularly, and expediting releases.

However, news reports have surfaced detailing CDCR’s shortcomings in these areas. In August, IVN San Diego reported that CDCR employees would often have to wait ten days for test results. Other reporting has focused on CDCR’s failure to enforce mask mandates and provide effective social distancing conditions within its facilities, among other issues.

Currently, CDCR has been working to revamp contract tracing efforts throughout its facilities. Prevention and Response teams, which consist of four employees tasked solely with contract tracing, were erected in October, specializing a job previously done by a single public health nurse at each facility.

Employees and advocates such as Canson, however, are critical of the CDCR’s recent efforts. One employee, speaking in anonymity to IVN San Diego, spoke to a lack of training among contact tracers, mentioning how these individuals are often “waiting around for direction on what to do.”

“We’re not fully trained or operational,” the employee admitted.

Canson also shares concern for the new contract tracing strategy.

“What my son tells me is scary,” she told IVN. “He said they see someone coughing, but they don’t remove that person right away.”

In Canson’s mind, this contributes to an atmosphere of panic within prisons.

“I know it’s hard to control the spread (of the disease),” said Canson. “We all know that. But the inmates can be much more proactive in doing their part if they had the information they needed. My son said he doesn’t even have access to sanitizer.”

CDCR Staff

There have been at least 4,373 cases of COVID-19 reported among prison staff. 10 staff members have died while 3,890 have returned to work. 483 individuals are still COVID-19 active.

CDCR Comparisons – California and the US

According to the Marshall Project, California prisons rank fourth in the country for the highest number of confirmed cases, following Texas, Florida and Federal prisons. California makes up 9.6 percent of total cases among incarcerated people and 5.7 percent of the total deaths in prison.

California also makes up 11.8 percent of total cases and 11 percent of total deaths among prison staff.

Division of Juvenile Justice

As of Oct. 30, there are no active cases of COVID-19 among youth at DJJ facilities. 70 cases have been resolved.