By Koda Slingluff

This account is part 5 of the Vanguard’s series on COVID-19 stories from CDCR. Click here for part 4 and here for part 3.

Orlando Smith is a thoughtful artist and reporter incarcerated at San Quentin. The Vanguard has had the privilege of speaking with Smith on multiple occasions regarding the prison’s conditions during the pandemic.

Smith’s sentiments gracefully weave together aspects of his incarcerated experience with Covid-19 related racism, indifference, frustration, and ever-present fear.

He began by saying, “The reality is simply the same systemic racism. Racist prison guards, an administration that’s indifferent to the incarcerated population. A guard union run by ‘proud boys.’ Yes it should be a collective idea of solidarity in the midst of this deadly crisis. It just isn’t so.”

He added, “CDCR has turned isolation into punishment because that’s what they do.”

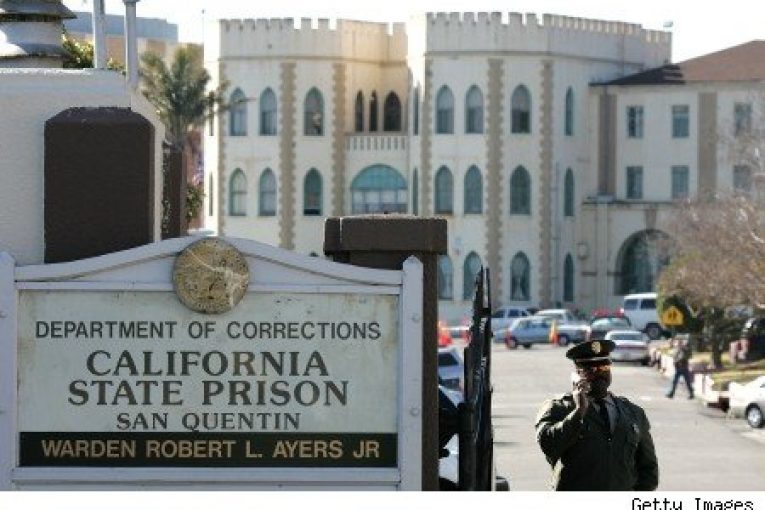

As of Dec 28., San Quentin houses a population of 2,758 people. It has reported 28 total deaths and 2241 cumulative confirmed cases.

“Far as social distancing… impossible!” Smith told the Vanguard. “This prison is over packed. They say it’s back to design capacity (single celled) but for most part 80% is still double cell living.”

San Quentin’s design capacity is 3,082 people. A month before the prison’s first outbreak, CDCR’s Population Report showed them at 122.5% of capacity.

Even before the outbreak, the prison conditions were concerning. Ivan Von Staich, who was also incarcerated at San Quentin, filed a petition alleging that the prison was not prepared for coronavirus.

Von Staich’s age and respiratory problems made him vulnerable to infection, and he worried for his health when what he saw as inevitable came along.

Shortly after his petition, the prison experienced an outbreak in which Von Staich, and 75% of the population, contracted the virus.

He alleged that the prison acted with deliberate indifference toward their health by not adhering to public-health experts’ recommendations to CDCR.

Hearing this petition, the California Court of Appeals agreed that the indifference met the standard of ‘cruel and unusual punishment’ prohibited by the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution.

The ruling stated, “We agree that respondents— the Warden and CDCR— have acted with deliberate indifference and relief is warranted.”

The court ordered San Quentin to reduce its population, stating, “The Eighth Amendment violation currently existing due to insufficient space for the necessary physical distancing will continue unless and until the population at San Quentin can be reduced to the 50 percent level.”

Since Sept. 14, San Quentin’s population has fallen from 3131 people to 2,758 people on Dec. 28. But the prison is still far from the 50% mark of holding only 1,775 people.

From Orlando Smith’s perspective, the prison is against releasing people to reduce the population.

“The strictly enforced rule is simply to write an RVR so it can delay release for disobeying a direct order, especially these for the board (parole board)” he said.

An RVR is a Rule Violation Report that prison staff can file regarding an inmate. RVRs are for misbehavior of all sorts, from vulgar language to possession of contraband, and are classified under 3 levels of severity.

According to the CDCR’s handbook, A serious rule violation (the highest level of severity) enables “prison officials [to] hold a person who is charged with a serious disciplinary violation beyond their release date while the charge is pending.”

All levels of RVRs can be considered when determining if someone is suitable for parole.

“Now coming from the top brass the guards are instructed to write RVRs for the smallest tiniest infractions… I received one on Oct. 15 for having a sheet around my bed (curfew) while I slept,” Smith stated.

Yet with rampant RVRs keeping people from early-release, San Quentin still must reduce its population to 50%. Another option on the table is to transfer individuals to other facilities.

On Dec. 14, a plan to transfer 300 individuals from San Quentin to other state prisons was announced. The plan was dissolved after activists and lawyers pushed back citing concerns with spreading the virus to other prisons, and instead advocated for releasing those in question.

Ironically, the initial outbreak at San Quentin resulted from a similar transfer.

The 121 men transferred from California Institution for Men (CIM) were considered medically vulnerable and the transfer was meant to protect them from the virus.

The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, an Oakland-based organization which has worked with Orlando Smith, argues that new transfers will enable outbreaks rather than limit them. They advocate for the responsible releasing of vulnerable people back to their communities.

To help with this effort, the Center has provided a virtual toolkit with activism suggestions, petitions, guidance for incarcerated people and more.

Smith passionately endorses releases, saying, “The only way to address this problem is for mass release. Keep in mind, this can be done because SQ’s mainline is low-risk incarcerated people at a non-designated prison. It’s not a difficult decision! It’s just another example of inequities in the penal system that is traditional American historical context… ‘black lives don’t matter.’”

San Quentin mostly houses level II offenders. CDCR’s statistical report shows that in September, about 75 percent of the population were level II or below.

These lower-level offenders seem far less threatening to Smith than how they are represented in the outside world.

“SQ news did an article 2 months ago back on Covid-19 deaths at SQ and it only mentioned death row inmates. It wasn’t disinformation, it was more like inflated rhetoric or shall I say, the shady art of mental manipulation.”

Smith expressed anger with the dehumanization of himself and fellow incarcerated people. San Quentin is the only men’s death row facility in California, which colors the public opinion and coverage of the human lives inside.

“It was a ruthless idea to encourage the reader not to be detained by emotions, but stimulate feelings of ‘they had it coming,’ or ‘they was already sentenced to death.’”

He emphasized the dissonance between reality and public perception of these prisoners.

“Many people here have underlying health problems and [are] already sick with cancer and old age and the fact Covid-19 effect people differently.”

Smith continued, “The energies that went into that story were dark, with the inability to report a full story about the other two-thirds of incarcerated humans who succumb [to Covid-19].”

“Everyday I and many others are in imminent danger, especially the elderly and immunocompromised incarcerated humans of SQ. It’s exactly how I illustrated in my Covid-19 vs. the nameless.”

COVID-19 vs. The Nameless is an illustration by Smith that can be viewed here. Among the informative statements in the piece is a stirring phrase: State institutions are not biocontainment facilities.