By Alana Bleimann and Layla Mustafa

SAN FRANCISCO – While the COVID-19 pandemic has continued to devastate the country and claim the lives of many, it has also exposed appalling shortcomings in the penitentiary system. It is apparent that jails and prisons cannot handle the combination of mass incarceration and a deadly virus.

However, while many have paid close attention to the countless failures at prisons and jails, there is an additional offshoot of the criminal justice system that has garnered far less attention.

Halfway houses– reentry facilities for those exiting prisons or jails and integrating into society– have put residents and surrounding community members at a dangerously high risk of exposure to COVID-19.

Residents of halfway houses are living under a strict set of rules and surveillance. They are are typically responsible for their personal finances, healthcare, maintaining employment with outside entities, etc.

GEO Group is one of many private prison organizations that operates halfway houses across the country. They advertise their programs as “leading, evidence-based rehabilitation” that individuals receive “while in-custody and post-release.”

Since GEO is a private entity they do not have the same pressure to make statistics on infection rates and outbreaks in custody publicly accessible. The public is essentially left in the dark regarding halfway-house safety.

GEO has also circumvented and violated Department of Public Health guidelines at Mesa Verde Detention Center which recently experienced a massive outbreak over the summer. The company’s failure to address safety concerns at Mesa Verde was exacerbated by their refusal to answer questions during court proceedings as well as providing false testimony.

Including Mesa Verde, GEO maintains 14 facilities in California alone. These 14 centers are a part of the 123 secure facilities the company manages in the U.S.

For those coming from prison under parole or probation, GEO “provides…temporary housing, employment assistance, rehabilitation, and substance abuse counseling, and vocational and education programs,” according to their website.

By itself, the continued movement and transfer of individuals from federal prisons, state prisons and jails into these facilities poses a high risk for the spread of COVID-19. It also puts the oftentimes low-income communities surrounding these halfway-homes at serious risk.

Former GEO residents– Mr. Johnny Talyor and Mr. Michael Doe can attest to this. In an interview with the Vanguard, they revealed what life was like inside San Francisco’s GEO operated halfway-house– 111 Taylor.

111 Taylor is a Residential Reentry Center (RRC) in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. According to their website, placements at the house typically last from six months to one year. Residents from federal prison are required to pay 25% of their income for subsistence, while those from state prison are not required to pay for living but must save 75% of net income in a savings account for their release.

Johnny lived at the facility for six months in 2020 after being released from state prison upon completing a 23-year sentence.

He promptly revealed that at the outset, and throughout his time at the home, the pandemic was not handled correctly by staff. Basic protocols such as requiring masks, were not established until the first outbreak in April 2020.

The reality was– resident safety was not a priority until it was far too late.

The pandemic has revealed the many weaknesses of our overly populated criminal justice system, including the apathetic and undisciplined staff.

Whispers began to spread across the facility that Jason Carpenter, the Assistant Facility Director, had not been to work in almost three weeks. Many began to consider the worst – had Jason contracted the virus? And if he did, who else may have it?

For those three weeks, residents were left out of the know. They continued to share spaces, attend work, and live under a roof with minimal safety guidelines at best.

Finally, the facility realized that they would need to address the amplifying concerns, and issue comprehensive mandatory testing to assess the casualties.

According to Johnny, once everyone was tested, about 9 to 11 positive cases were immediately discovered.

With this news, the fear and panic that had been bubbling up over the past few weeks came to a boil – many residents petitioned for their release or at the very least requested to be quarantined in a hotel for the meantime.

Johnny tells us that positive cases were quarantined at off-site hotels and monitored by city doctors.

He recalled observing one man who had returned from the hotel after having tested positive, in a matter of weeks “he had lost 25-30 pounds.”

Following the initial tests that revealed the outbreak, Johnny explained that residents were tested a second time, and 100 percent of them were negative, meaning that DPH no longer labeled Taylor as a risk and therefore would not provide any more testing at the house.

Johnny added that GEO tried to send people to Color Testing on Pier 30, for a third round of testing but residents were required to schedule times on their own. As a result, many were not tested again.

With the outbreak gradually slipping into their rearview mirror, Taylor finally decided to mandate masks and began providing daily cleaning supplies.

According to Johnny, following the April outbreak, some changes were made in how residents would come down the stairs, and how they would use shared spaces.

Luckily for Johnny, he was housed on the fourth floor, which was equipped with tables, microwaves and an ice machine. He could avoid interacting with the other floors as a result. Those on the other three floors, unfortunately, had to continue to share common spaces, though “no mingling was allowed.”

However, the rules that were implemented seemed to be poorly enforced and fickle.

While residents were only meant to go to work, many still went to malls and local eateries. Johnny says that at specific times during the day, staff would come up to the resident’s rooms and conduct a temperature check on whoever was there. But there were no temperature checks for those entering the building

Prior to the pandemic, rooms at 111 Taylor either housed 14-15 people, 4 people or 2 people each.

Staff created 4-5 empty rooms for quarantine, but larger rooms still housed up to 7 residents. Even after the outbreak, Johnny continued to be housed with another resident who was not employed.

This means that when Johnny left the building for work every day, his roommate had to hope that Johnny had not contracted the virus during his time outside the facility.

A shared room of 7 residents all working different jobs, and traveling different distances across the city, hardly seems like a stable prevention tactic against the virus.

So while prisons and probation continued to deny early-release for many halfway-home residents, Taylor’s efforts to downsize and mitigate risk was put to the test against the force of the pandemic raging outside.

According to residents, this response was less centered on safety and concern, but instead on discipline and stress.

Johnny indicated that once the COVID-19 protocol became stricter, the food provided at the facility quickly deteriorated. The quantity was scarce and it was cold most of the time.

He also recalled hearing rumors of staff beginning to tamper with resident’s passes or harassing residents who did not behave like, “GEO wanted them to.”

Residents use passes to enter in and out of the building. It specifies if they are allowed to leave, how long for, etc. If a resident’s pass was “tampered with” it could affect their ability to go to work or exit the building.

Another former resident, Michael, reported numerous instances of staff mismanagement during 111 Taylor’s second outbreak in early January.

Michael was hardly in the facility, as he spent the majority of his time at work. He would wake up at 5 a.m. and get home around midnight.

He emphasized the staff’s mediocre response to sanitation policies and stressed their unwillingness to treat their residents with dignity.

Recently, San Francisco Bay View editor, Keith “Malik” Washington, spoke out regarding his experience during January’s outbreak at 111 Taylor. Washington filed a lawsuit against the Federal Bureau of Prisons and GEO, after his phone was confiscated and he was prohibited from speaking to the media. This response came after his 48hills interview where he disclosed the facility’s unethical and ineffective responses to the pandemic.

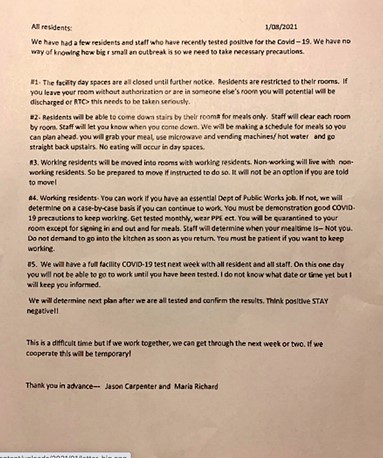

In the interview, Washington detailed the severe lockdown restrictions placed on residents and provided a photo of the letter given to them. The letter imposed the restrictions and fortified these new directives with threats to turn residents back into custody.

According to Michael, the rules began to get so restrictive that Taylor became “almost like a prison.”

Along with these severe lockdown restrictions, Michael revealed that there was also a lack of cohesiveness in implementing and enforcing these rules.

He says, “there are a lot of arbitrary decisions being made by individual staff members.”

Both residents and staff were tested at the start of the January outbreak, but this was the only time testing was enforced or encouraged.

“The place is very mismanaged,” he added.

With poorly trained staff, unclear rules, and a growing emphasis on discipline, tensions began to rise for both residents and staff.

For Michael, this came to a head when he had a disturbing run-in with a staff member in the middle of the night.

He was sound asleep when he woke up to someone “banging on the bed with a clipboard.” Naturally, he was startled after having been harshly awoken at 1:00 in the morning.

The female monitor questioned Michael about his number, despite her already having access to that information.

Michael clarified that on each person’s bed, there are tags with a numerical identifier, but in the time-span that he was at the facility these tags had yet to be placed on his bed. It was out of his control that the tag was gone, but the staff member continued to demand for it.

Initially, he didn’t think her actions were out of malice, as he assumed she had been poorly trained and did not understand how to navigate facility procedure.

The tense discussion led to an exchange of angry words and after some time he was finally allowed to go back to sleep.

The following day, he resumed his morning routine, going downstairs to check out of the facility for work. But he was not allowed to leave.

The staff member working at the front door informed Michael that he could not depart for work because Michael was, “on lockdown and I don’t know why.”

Confused, he headed upstairs for a morning coffee, but at this moment, he ran into the female monitor from the night before.

Michael, reminded of last night’s events, informed her that he would move to file a grievance against her. The monitor responded with screams.

Multiple other staff members had to restrain her and wave her down, in order to make the yelling stop.

Michael returned to his room where he received a phone call from his parole officer. He was informed that the monitor had filed a report following the night’s events that claimed Michael had threatened her.

He maintained that this was a complete farce, but unfortunately, his testimony was not enough.

At the time, this claim was a violation of his parole, leaving him no choice but to be sent to SF County Jail.

Upon arrival at the jail, Michael received a COVID-19 nasal test and was placed in a holding cell for 12 hours.

After 12 hours, his test came back negative and he was released into the general jail population.

This testing protocol does not match the jail’s official testing guidelines, which states that transfers from another facility must quarantine for at least 14 days even with a negative test.

An exception may be made, if the transferee is “cleared to bypass quarantine by MD.”

However, it would be surprising if Michael was cleared, because he had gone to work prior to his transfer.

After 5 days in custody, his parole officer was able to review video footage from the kitchen at Taylor which revealed the female staff member yelling at Michael.

Since there was no evidence, and no witnesses could confirm that Michael had actually made any threatening comments, he was effectively released from the jail and did not have to return to 111 Taylor.

Michael feels this incident happened due to a lack of proper training.

The stories of Johnny Taylor and Michael reveal that private halfway houses have slid under the radar and have become hotspots for the spread of COVID-19.

Recently, however, the Adachi Project released its first film, “One Eleven Taylor (During a Pandemic)” in which multiple residents describe the first outbreak they were forced to endure.

In the film, the videographer corroborates much of the testimony we received from Johnny on the initial outbreak.

The documentary- which was filmed in April 2020, highlighted the lack of guidelines and protocol leading up to and throughout the initial outbreak as well as the overall lack of transparency for both residents and the public. The videographer claims that by the time he left the facility, there were around 12 positive cases.

The videographer confirmed the claims of Taylor’s mismanagement, alleging that prior to the outbreak staff informed residents that, “you don’t need masks unless you already have coronavirus.”

Additionally, the videographer claimed that during the first outbreak in April, “the big problem is the seven people that tested positive- they put them in that 14 man room with 7 other people that were not positive.”

One resident was interviewed while he was packing his bags to leave the facility. According to the videographer, the man had been discharged, but Taylor had made no plans or arrangements for his stay once he left. Meaning, that he would be ejected from the building, in the middle of a pandemic, with no employment or home. Allegedly, the facility needed his bed for an incoming resident.

It begs the question of what purpose does 111 Taylor actually serve?

If GEO is meant to provide, “temporary housing, employment assistance, rehabilitation and substance abuse counseling, and vocational and education programs,” but residents are only receiving unsafe temporary housing during a time when they need it most, why should residents have to stay there at all?

Taylor’s mishandling of proper COVID-19 health protocols and GEO’s overall ineptitude in protecting their residents is exacerbated by their astounding lack of transparency.

The videographer and ex-resident poignantly states, “People are banking on the fact that if you are not used to freedom they don’t really have to give it to you.”

Contact with GEO and 111 Taylor has been attempted on multiple occasions, but it has been unsuccessful.

The film and its imagery only intensify and affirm the testimonies received, and it is clear that Johnny and Michael’s stories are just one of thousands.

It is certain, however, that there needs to be more attention on private prison organizations that have slipped under the cracks. GEO and Taylor’s administrators must be condemned for their callous endangerment of their residents, and the surrounding community in the Tenderloin district, who deserve better care.