by Robb Davis

On Tuesday, June 1, 2021, the Davis City Council created a budgetary “placeholder” to fund a new position to oversee social services. This article argues that the position should focus on public health and safety and be a director-level position.

Summary

While police departments have taken on many public health-type functions in cities across the US, they are not designed to address public health challenges effectively. Davis already has various public health programs related to homelessness, youth diversion, and mental health crisis interventions. A public-health-trained Director of Public Health and Safety can lead a small department to focus on greater coordination of current efforts, help the City Council set clearer programmatic priorities, leverage County resources, and create synergies with UC Davis, DJUSD, and non-profit organizations in the City. To advance public health efforts, the City Council should create and fund a new director position that reports to the City Manager.

Background

Cities across the US are (re)examining their police departments’ purpose, function, and role. Beyond the rhetoric of “defunding” the police, are essential questions about the militarization of local police forces, protections afforded to police officers (so-called “qualified immunity”), systemic racial bias in policing, the appropriate role of police in mental health crisis response, and the role of armed officers in routine code enforcement.

There is little argument that the police in many cities have become the de facto public health response unit for diverse challenges like domestic violence, substance abuse, school violence,  general welfare checks, homelessness, and mental health crises. Some of these responses may even be built into laws and policies.

general welfare checks, homelessness, and mental health crises. Some of these responses may even be built into laws and policies.

And yet, police forces are not public health agencies. They are not structured or trained to analyze the root causes of public health challenges. Moreover, they do not evaluate outcomes based on an understanding of the social determinants of health. As a result, when they respond to a crisis, it is long past the time to consider primary or secondary prevention strategies.

By the time police departments are called to “deal” with these issues, they are already at a very late stage in which only drastic “health interventions” or “palliative care” can provide a reasonable response. And yet, we continue to call upon the police to “solve” these complex public health challenges because we have created too few alternatives.

Our public health approaches are fragmented — held hostage to short-term funding cycles, changing priorities, and too little focus on creating durable local partnerships to engage in primary and secondary prevention programs. They do not adequately leverage local resources, expertise, or community support to develop relational approaches to confront our significant public health challenges proactively. Instead, we too often use the only tool at hand — the police — to staunch the bleeding.

It is legitimate to ask: “What are the things that police are uniquely qualified to do?” What follows will not attempt to answer that broader question, but it takes as a given that the police are not well-positioned to lead the response to local public health challenges, nor are they the keystone of public safety.

Without clarity about what is required to improve health and safety in our community, we will continue to revert to the police as the “answer” to public health challenges. Without envisioning a system — including staffing and funding priorities that achieves our ends, without a clear set of ideas of how change happens — we are left with the police as the “essential” organization in the City government to respond to adverse public health outcomes.

Our Current Public Health Challenges

While city-specific data on public health challenges are rare, we can look at County-level data and the limited studies we have to outline the critical public health challenges in our City. In addition, COVID-19 has revealed that sub-populations within Davis are more likely to suffer from broader systems failures common in communities across the US. Finally, we can also look at the programs Davis already provides via County contracts and its funds to enumerate the challenges.

They include the complex syndrome that we refer to (too simplistically) as homelessness. It hides various challenges, including untreated mental illness and substance use disorders and the still poorly addressed challenge of untreated childhood and lifetime trauma.

They also include substance use disorders not directly related to homelessness, and untreated mental health conditions among young people. Among the same group, there is also the challenge of obesity linked to poor nutrition (which in turn is related to too-high levels of food insecurity and poverty[1]), which are precursors for lifelong health problems, including Type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic and the changing demographics of Davis have revealed how vulnerable low-income seniors are — given poor nutrition and isolation.

This is not an exhaustive list, but data from various sources — provider and County. Indeed, programs that the City and the School District have developed indicate they are priorities.

A Director and Department of Public Health and Safety for Davis—Function and Structure

A Director and Department of Public Health and Safety will

- focus on greater coordination of current public health efforts,

- help the City Council set clearer programmatic priorities,

- leverage County resources, and

- create synergies with UC Davis, DJUSD, and non-profit organizations in the City.

The key to the Department is to have a qualified Director who can coordinate local efforts and provide critical data analysis for decision making. The Departmental staffing is limited by design and buttresses County efforts, in no way replacing or duplicating them, but rather leveraging them for more significant impact.

Launching it would allow all current public health and safety activities to come together into one department with limited additional staff needed. The Department would also produce an annual report on public health and safety for the Council and be a clearinghouse for data from all City activities connected to health, safety, and wellbeing.

There are several historical and practical challenges to developing a separate Department of Public Health and Safety to address these priorities. Still, the cost of not managing them proactively and comprehensively indicates the need for a City Department to coordinate efforts related to them.

In fact, in recent years, the City has created new positions and used consultant services to formulate successful programming to address homelessness (as one example). The consultant has helped build accountability structures around these programs and brought in resources for the Bridge to Housing and Employment and emergency shelter programs, as well as significant funding for Paul’s place. Imagine what a full-time staff person tasked with developing community health and safety programming could do to increase funding and build programming accountability.

In fact, in recent years, the City has created new positions and used consultant services to formulate successful programming to address homelessness (as one example). The consultant has helped build accountability structures around these programs and brought in resources for the Bridge to Housing and Employment and emergency shelter programs, as well as significant funding for Paul’s place. Imagine what a full-time staff person tasked with developing community health and safety programming could do to increase funding and build programming accountability.

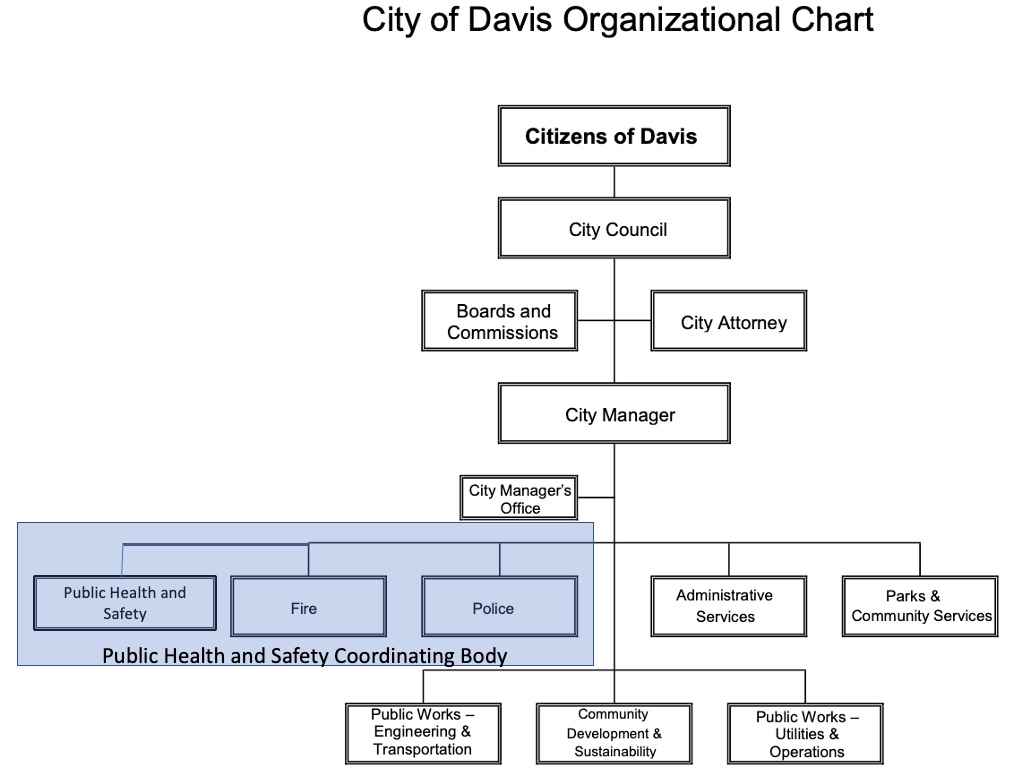

The two figures show a Public Health and Safety Department’s place within the current City structure, and how it could be structured internally to coordinate programming and launch new initiatives.

First, note that the new department would combine with Fire and Police to form a public health and safety coordinating body. The purpose of this body is to analyze public safety across departments, share and discuss data, develop the template for an annual “public health and safety report,” and look for ways to streamline public safety services in the City to avoid duplication and assure efficient use of resources. The Department of Public Health and Safety is headed by a Director who reports to the City Manager. The position oversees current programs and develops new ones in priority areas.

The second figure[2] illustrates the key divisions within the Department and demonstrates that solid data analysis, program evaluation, and interagency collaboration are central to its mandate. It also calls out this department’s potential to coordinate reporting on public safety-related code enforcement in the City. Not all code enforcement is safety-related (think parking enforcement), but much of it is. The Fire Department, the Planning Department, and the Police Department carry out most code enforcement actions. Creating a new Department will enable the City to “step back” and ask about the best ways to carry out, coordinate, and, most importantly, report to the City Council and community about code enforcement actions and results. Having a coordinating body will enable the community to understand better the role of code and code enforcement in keeping citizens safe. It will also permit a re-evaluation of the best ways to carry out enforcement.

The ideal candidate for the Director role is public-health-trained with a solid epidemiological background and community-based programming experience. The department’s staff can be lean with the Director heading all current initiatives until funding for new initiatives supports division heads.

It is essential to point out that City staff do not implement programs for the most part. Instead, high-quality local non-profits, like Communicare, HEART of Davis, and YCRC, receive contracts to implement programs. This is consistent with current practice in programs such as the Davis Emergency Shelter Program, the Respite Center Program, the Youth Restorative Justice Program, and Project Roomkey (all existing projects). These programs receive funding from County and State grants and general fund dollars designated for community priorities.

A key in this model is Community Health Workers — called “Navigators” here — to extend services and build truly relational programming.[3] Navigators are a critical part of the Department’s service delivery and are a feature for which Davis has unique opportunities. Given the presence of the University and many healthy and knowledgeable retirees, recruitment of high-quality navigators who speak a variety of languages will enable a deepening of services in any of the programmatic divisions.

Perhaps most importantly, the Department will be a hub of activity that links the City collaboratively with the University and School District on programming and draws from University research and expertise to test new programs and provide students with learning opportunities. Healthy Davis Together (HDT) has forever changed how the City, School District, and University view collaboration to solve real-world problems. HDT has shown that the three agencies can face a significant challenge and coordinate activities with County health officials to achieve impactful outcomes.

Having a Department that builds upon and enhances these new and still evolving partnerships will extend health and harm reduction programming developed for UC Davis students and staff into the community. It will create a city/university learning environment in which new programs can be tested, evaluated, and improved. It will create synergies that will extend dollars from each entity’s budget to improve the wellbeing of the Davis community.

Having a Director of Public Health and Safety will strengthen the City’s voice at the Yolo County Homeless and Poverty Action Coalition (HPAC). It will help the City to place and coordinate resources flowing from the County more effectively. And it will enable greater accountability towards the Citizens of Davis.

Paying for it

An obvious question is how the City pays for this new full-time senior position to staff. The first answer is that budget decisions are about the relative City priorities, and my experience on the City Council indicates what we value we will fund.

Citizens in Davis pay additional annual taxes to fund the purchase and maintenance of open space and pay for parks and our library. In addition, we tax ourselves to provide maximum programmatic choice for students in our schools. These are our choices, and we staff programs based on these choices.

We, that is, our City Council, can decide to move general funds to hire a Director of Public Health and Safety. This is a choice.

It appears from Tuesday’s decision that the City Council is prepared to find the funding from a combination of sources — including American Rescue Plan funds and by moving funds from other City programs. This demonstrates that there is the political will to make this change. This is the first and most crucial step.

The decision is about priorities. We have already decided that we must more actively address homelessness, mental health crises, and youth challenges in Davis. Funding a new position takes the next step to assure that the benefits and reach of such programs are maximized by having staff devoted to overseeing their implementation and impact.

Power Dynamics and Institutional Change

To close, I return to a consideration of the role of the police in this and any city. Police and Fire are the two premier public safety institutions in any city (while programs like wastewater, solid waste disposal, and water are essential broad-based public health services).

Whenever public health and safety are a topic of City concern, the Davis Police and Fire Departments are “at the table,” both figuratively and literally. The City Manager and the City Council thus hear, consider, and give weight to their perspectives. They “frame” issues according to their view of how the City should solve its public health and safety problems.

This framing gives these departments significant power to determine the public health and safety programs the City will carry out, as well as recommend budgets to carry them out. And yet, while both departments play a role in public health and safety programming, neither views problem-solving from a public health perspective. With limited exceptions (inspections and pro-active code enforcement), both departments are “responders.” They respond when situations get out of control — when public health and safety are under threat. They are not primarily concerned with primary or secondary prevention.

A Director of Public Health and Safety position creates a new voice — a new framing of solutions — within the City. It is a “power center” with a unique perspective about the role of prevention. Given the nature of public health practice, it is also a center that seeks cross-sectoral collaboration and multi-disciplinary problem-solving. This is the unique contribution that a Department of Public Health and Safety brings to the City of Davis, and I believe it is past time to create it by hiring a Director of Public Health and Safety as a first step.

______________

[1] Space does not permit a full development of the social determinants of these health challenges but poverty, poor access to care, and racial and linguistic exclusion from information and resources are critical to many of them.

[2] Items highlighted in green are existing programs and activities. The red dotted line illustrates staffing that is not City employed but is privately contracted via non-profits or other organizations or is volunteer. One exception is the extensive senior-focused programming that the City already has. Those programs would be moved under the Director of Public Health and Safety in this model.

[3] For more on Community Health Workers (CHW) see here, here, and here.

Robb Davis is former Mayor of Davis. To discuss this article with Robb you can contact him at: 530-564-9861 or email him at robbathome@gmail.com

Support our work – to become a sustaining at $5 – $10- $25 per month hit the link:

I concur with Robb 100% and thank him for providing this blueprint.

Regarding the question of how to pay for it, in the short run (the next 36 months) American Rescue Plan funds can be used. In the long run I strongly believe that If we had an integrated Public Safety Department where all personnel are cross trained to handle the full range of public safety needs, I suspect the budgetary needs would actually be decreased from the current model.

Organizing the department where there is a small portion of the department whose primary focus is reacting to, containing and deescalating incidents (fire, medical and/or policing) would leave all the rest of the department for unarmed presence in the community’s neighborhoods, where the interaction between the public safety officers and the members of the public is centered around the question “How can I help you?” rather than the question “What are you doing?” That would mean the public’s first reaction would be to look at the face and eyes of the public safety officer rather than at the officer’s hips, looking for the danger implied by the presence of the gun and holster.

“how can I help you?” is one of the most passive-aggressive, annoying and insincere questions ever asked. The best answer is, ‘get the F out of my face’. Changing the wording doesn’t change the intent of the question.

Agree on having “how can I help you” and “what are you doing” assigned to the same job role is a recipe for mistrust.

Meanwhile – in San Francisco, an apparent “crisis call” turned into this. Now maybe, a social worker could have “de-escalated” the guy, but who knows? Seemed like a somewhat unpredictable response – as can be expected at any time. (Not sure what crime brought the police in the first place.)

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/video-shows-asian-female-police-officer-attacked-man-san-francisco-n1269469

I didn’t realize that one might face “hate crime” enhancements by attacking a police officer. By the way, is this partly a result of having women (or small men) on the force? When you call the police (especially if they’re by themselves), do you feel better having someone stronger than yourself (at least) show up? And might that actually be safer for everyone, rather than relying upon bystanders to break it up?

What is the “opportunity cost” (e.g., options other than using those funds for something that would remain unfunded beyond 36 months)?

Is this what the American Rescue Plan funds were meant for?

https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/American-Rescue-Plan-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Thanks – skimming through it, it seems quite different than what’s being proposed here.

I suspect that there’s additional documented guidelines somewhere (e.g., that would be referred to if the use of funds is ever audited).

I’m starting to wonder about the use of all of the federal money that’s flowing to states/cities as a result of the administration’s response to Covid.

“What is the “opportunity cost” (e.g., options other than using those funds for something that would remain unfunded beyond 36 months)?”

What is the cost of keeping things the way that they are now – a system that we know doesn’t work?

And let’s be honest. The reason for moving duties away from the police has never actually been justified, other than to those who were already convinced (the “usual suspects”, you might call them). Other than some vague “fears” from that same group as reported on here – some of which are highly questionable, and some of which seem downright inaccurate.

Unless the underlying cause is addressed (e.g., a more complete and costly response to homelessness that the city is purposefully encouraging and enabling), the question of “who” responds to “crisis calls” is not the biggest problem. It’s generally the same individuals who experience “crisis-after-crisis” – in any given city.

As far as what else the temporary funds can be used for, Keith provided a link which seems to describe its purpose.

Yes Ron, here’s the actual text:

“The reason for moving duties away from the police has never actually been justified”

Even most police chiefs will tell you that police are not well situated to respond to mental health crises. Darren Pytel said that pretty clearly during his presentation as did Karen Larson.

“Mental health crises” are generally not something that can be successfully addressed by a response team on the street, whether it’s police or someone else. Other than perhaps a temporary reprieve, at best.

That’s what the health care system is for. Though police (or anyone else) can “deliver” someone to it.

But again, I’d suggest an examination of “who” is generating the crisis calls, as it’s generally the same people repeatedly – in any given city. And if a city is purposefully encouraging/enabling those folks in the first place, you’ll get plenty of “crisis calls” as a result. Along with all of the other costs.

The vast majority of people are not experiencing “crises” that they would call the police for. Nor do they call the police for “mental health crises” for someone else, as long as they’re not committing a crime.

Actually those are the people that HAVE to address an actual crisis.

Ron, several years back my next door neighbor had seven 911 calls within a six-month period. Clearly he fit into your description of the “same people repeatedly.” Every one of those seven 911 calls was medically appropriate. The state of his medical health was at that level of need. Are you proposing that he should not have received that level of public safety support?

These are choices that were directly voted for by the citizens.

Would that the citizens choice or just the City Council’s choice?

Either way, it’s an outrageous and irresponsible suggestion for a city that already claims to be fiscally-challenged.

This is my fifth comment, and hence – the last one I’m allowed.

Ron, if our fair City acted on Robb’s suggestion and brought Police, Fire and Emergency Medical all under a single department, and then rationalized those services using the available skill sets of the full complement of employees, I believe (dare I say strongly believe) that such an integrated public safety model would deliver a higher quality, safer, less confrontational, more proactive level of public safety services at a lower cost to the taxpayers. The current amount of “waiting for an event to happen” time that exists in the current siloed structure produces a substantial level of inefficiency.

Sunnyvale California has been delivering integrated public safety services from a single department for over 70 years. NPR’s Marketplace has reported on Sunnyvale. Palo Alto is reportedly looking at the Sunnyvale model. CBS San Francisco has reported on Sunnyvale as well.

If you transformed the fire fighters’ “waiting for a call” time into “out and about” connection time with the community, our city that is fiscally-challenged would see both an efficiency and effectiveness gain … with a significant portion of the gain being in the service areas that Robb Davis has described.

My point here is that we have direct and representative democracy. Priorities are set by the City Council whether you like or agree with them or not. Others are voted on directly. In either case, our budgets demonstrate our priorities. I am making a case in this paper (whether you agree or not), that this position should be a priority. If it is, we can pay for it. That is my point.

The Vanguard just ran two articles about a new Davis noise ordinance where it was expressed that the council should not be making that decision without more community input and commissions. So much for representative democracy at least when it came to that ordinance.

In relation to this article there has, thankfully, been significant input via the joint committee from the Social Services, Human Relations, and Police Oversight Commissions. This piece merely fleshes out a vision for one of the nine recommendations. So, this has been quite different from the example you raise.

Keith – they had three commissions work on this. The recommendations came out of the work of the joint subcommittee of HRC, Police, and Social Services and were passed unanimously by all three full commissions.

How much real overall community input has there been? Or is it just input from the usual small crowd of community activists who are always the loudest? Is the community really behind funding a whole new organization with administration and staffing costs at a time when Davis can’t even hardly keep up with repairing its own streets (which BTW the voters said NO to a new street repair parcel tax)?

Anyway that’s my 5th and final comment for today so if I get questions I can’t respond until tomorrow.

Community input is process based – as Robb points out there was significant commission involvement in this issue with public meetings. On the issue highlighted earlier this week, there was none. That’s a significant difference.

In addition, I would be remiss to not point out more than 750 people signed onto a letter supporting the nine recommendations. There were at least three council meetings on it, including one in December where there were more than 150 public commenters. Short of land use issues, this may be the most discussed issue in recent history. I would wager to guess in Davis, the community is overwhelmingly behind measures like this.

(I must also point out you posted three comments two with links to the American Recovery Act and the other posting the language verbatim – you would have had ample opportunity to have offered additional responses if you had left it at a single comment and moved on).

Something else to think about Keith – no pushback from the police. Not from the police chief. Not from the POA. And they certainly are aware of what’s going on.

I just don’t think you have any legs to stand on here in terms of process or input. There was more than ample opportunity for it.

750 out of 65,000, impressive.

Basically short of a plebiscite on each issue, you think the no level of participation is sufficient

The possible problem is once you hire a DH, you will probably grow a department to support it… not just one position… with all attendant benefits, office space, equipment etc.

As it stands, just one position… which, by itself should not be a significant problem… at this point. We’ll have to wait and see…

I totally agree with this.

Budgetary dispute is an area in democracy that can be solved without voting.

Suppose there is a police department and a not yet exist public safety department, each tax payer could just select the recipient of their tax portion in whatever ratio they want.

Without an APP doing that, all you really need is a survey. As long as the ratio reflects the actual divide in opinion, the budget reflects what the people choose.

That is democracy without winner takes all mentality.

Bill, that could be the outcome, but it does not have to be the outcome. The organization chart below available at this LINK shows one way to accomplish the described (dare I say desired) outcome with an actual reduction of one senior management FTE/position.

In Sunnyvale’s Public Safety organization, the Fire Chief and Police Chief FTE positions do not exist, with the Deputy Chief positions reporting to the Public Safety Department Head. Creation of the Special Operations Deputy Chief is an added FTE offsetting one of the two FTEs saved by the elimination of separate Chief positions for Police and Fire.

For over 70 years Sunnyvale has been cross-training all public safety personnel in the three disciplines of police, fire, and emergency medical services. This cross-training program is no joke; one Saturday CPR certification or fire safety class won’t cut it. Each public safety officer (PSOs) graduates from both a police and a fire academy, completes field training in both areas, and somehow in between is trained and certified as an EMT. Cross-training is extended to include even people out of the field, like dispatchers who are trained to handle all police, fire, and medical emergency calls.

Define ‘success’. The train station is trashed. That trash is brought in by the so-called homeless and left to pile up and blow around in the wind. What happened to the clean-up crew that used to come to the station a couple times per month and clean the station – did they realize they’d lost the war, and let the so-called homeless raise their litter flag to proudly wave in the hot wind on a tipped-over shopping cart?

Paul’s place, the Taj Mahomeless? A showcase for the City and associated non-profits to house the few lucky (and not necessarily clean nor sober) lottery winners in the clean & new? Wouldn’t it be better to stack some refurbished shipping containers and keep five-times the number of those truly in need from having to sleep in the elements?

Imagining . . . nothing’s coming to mind. Some may say my imagination glass is half-empty, I say my imagining is completely empty, no water, need a deeper well to drain the deep aquifer.

If there’s to be a change (which still lacks justification in the first place), it’s up to the fiscally-challenged city to show how they intend to pay for it. Prior to making a change.

Saying there’s no justification indicates it one or both of the following is true. One you didn’t read the article in which I provided a justification; two you don’t know anything about the public health challenges of our town. Your ignorance should not lead you to the conclusion that there’s no justification. Indeed it’s the police themselves who have raised the flag on many of the public health challenges in our town. Anyone paying attention over the past decade would have recognized that all of the things laid out in the article requiring attention Have been here for some time and are not getting any better.

Let’s break this down:

I did read the article (skimmed it, at least), and still don’t know what the justification is. That is, exactly what problem you’re trying to solve.

What exactly did the police say “needed” to be done, in regard to public health? Or, were they intending to simply point out that they are not “public health experts”?

As far as emergency responses, we’ve already got the police, fire, and ambulance. Along with hospitals, outpatient clinics and health insurance, which are intended to address “public health”. “Public health” was never intended to be addressed on streetcorners, and paid for by cities. This is a new “demand”, by some.

In what way?

Again, if you encourage/enable folks who are already likely to experience “heath challenges”, then that’s probably what you’ll get. Homeless individuals come to mind, regarding those who end up requiring a disproportionate amount of emergency services. Such as this one, which was a criminal matter:

Homeless Woman Violently Attacked In Davis Shopping Area – CBS Sacramento (cbslocal.com)

Were either one of these people (the unfortunate victim, or the perpetrator) being housed in a local hotel as part of “Project Roomkey”?

Or, how about the perpetrator depicted in the following video?

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/video-shows-asian-female-police-officer-attacked-man-san-francisco-n1269469

I view folks like you as social justice advocates in the first place, along with all of the baggage (good and bad) which that entails.

I don’t know of very many “public health challenges” (especially when it comes to mental health) that can be successfully addressed on streets.

But again, my original questions remain, even if you believe that there’s justification. That is, what problem are you trying to solve, how are you going to measure “success”, and how do you propose that the fiscally-challenged city pay for it? (Including any opportunity cost that would result from that decision?)

Truth be told, “social justice” is a popular topic at the moment, but one which seems more like an ill-thought-out (and perhaps ultimately fading) fad. Other than the true believers such as you and others associated with the Vanguard, where was all of the concern 5 years ago? And, what do you think will happen regarding the concern in 5 years from now, after the “relative newness” of cell phone and surveillance videos either wears off, or shows more of the crime that actually occurs?

First of all skimming is not reading particularly when you lack a full understanding of the topic to begin with. Second you derisively say “folks like you’ by that you mean people with doctorates from Johns Hopkins in public health? As usual you seem to be arguing against people that know a lot more about the topic and have done very little to inform yourself before you wade in with an argument. Did you watch either Darren Pytel’s presentation in December or Karen Larson’s presentation in April? What part of their presentation do you disagree with?

I will need an additional article to lay out the public health challenges, the metrics that you would use to determine success, and the evidence-based programs that are available to deal with them. Suffice to say that the other article in the Vanguard that dealt with the police officer who was charged with embezzlement displays a very interesting picture. That was a public meeting at which the police were laying out very emotionally, the challenges of teen substance use disorders. They were begging parents to take a more proactive approach and they were seeking solutions that would typically be found in public health interventions.

This article introduced them only in general terms. But the data about the need for preventive interventions is clear.

As far as the comments related to homelessness, there again you are ignorant of the successes we have had over the past five years with our bridge to housing program. More than 30 people have found permanent housing and all remain housed except for one who passed away. These interventions which continue to today or adding more and more people to the rolls of permanently housed. These are by definition public health interventions. Again your ignorance of what’s going on in the city is understandable but inexcusable if you’re going to opine about the effects.

The needs are clear and they relate to preventing mental health crises, substance use disorders, issues related to trauma, teen diversion programs, and the list goes on. Each program has its own metrics for assessing effectiveness. One of the challenges is we need someone in place you can lay out what the metrics are so that we can begin to develop programs that will address them in the assessments will follow.

I understand people’s concerns about this being a new cost center. But the cost already born by our community in terms of response to violence, mental health crises, substance use disorders, etc, are difficult to quantify because they are broadly spread across the society. Nonetheless they exist and they are substantial.

Previously:

So, just, what? Leave them on the street? Send them down to the next community?

O.K. I’ll just state that the problem (including problem description, quantification, and expected improvement) is flat-out not there.

No – I mean the usual “social justice warrior” suspects. Whether or not they have a Ph.D.

That’s a flat-out, unjustified insult. I do know quite a bit about some subjects that are discussed on here. But I would expect that a proposal to increase cost to the city (without telling us “where” it would come from, or “what” it would solve) might be spelled-out for those who aren’t “experts”.

No. Is that a requirement? What did they say? Are they recommending performing more “public health services” on streetcorners? Did they also have a recommendation regarding funding (which I assume they don’t think should come from “their” department)?

From what I’ve seen, “public health experts” always believe that more “public health experts” are critically-needed. (You can pretty much substitute that job description with any other, regarding that belief.)

You might not accept this, but public health experts are not on a mission from God – any more than anyone else.

So again:

1) What problem(s) are to be solved?

2) How will increased funding solve those problem(s)?

3) How will it be paid for?

4) What “opportunity cost” is there (in regard to where that money is coming from)?

5) What metrics will be used, to subsequently measure “success/failure”?

So, do you think those five recommendations (off the top of my head) are reasonable and should be spelled-out in a manner that’s understandable for anyone without a Ph.D., before the city embarks on a significant change?

This is the underlying question, isn’t it?

And if some cities start providing a “disproportionate share” of services, you can be sure that the “need” for services will continue to grow. You’ll have plenty of work for “public health professionals”, as a result (and as long as the funding continues and expands).

Maybe ask Eugene, Oregon, about that. Or San Francisco, Portland, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Venice Beach (part of LA?), etc.

Just don’t ask El Dorado Hills or Granite Bay, for example. Perhaps not even the vast majority of places within Roseville.

Robb…

My only concerns:

Second, and associated… will this (if it goes to full department) be a duplication of services/’meeting [addressing] needs’? A ‘competitor’ as it were? Would the “needs” better be met by City contributions to existing/enhanced services (ear-marked for improving services to Davis) to bolster their effectiveness?

Now, if a non-department head (much less danger of creating a duplicative department) position was created, with funding to also fund increased services, with the new position occupant charged with coordinating with the existing ‘infrastructure’ to make sure new Davis expenditures are well spent, and focus on new/enhanced services to Davis… then, just tell me where to sign the documents…

All questions meant/intended as fair ones… I recognize the “needs”, and the opportunities… what I question is the ‘delivery model’, likely effectiveness, and its costs… a bias… if you spend a bunch of money, effort, best to invest in improving/enhancing an existing system, than creating a new one…

Will hope for a fair response to my fair questions… I trust I’ll get that

I agree with you Bill that we need to have metrics to determine the success of programs. As you know I fought for this the entire time I was on the city Council, so this is not new to me. I find it somewhat interesting that this particular field is required to show metrics of success when many others are not, including the police and the fire. We accept them merely as part of our community without questioning whether they’re having a positive impact for the amount of money that we spend on them. But when we talk about public health all of a sudden we need to demonstrate beyond some kind of reasonable doubt it will have a positive impact and will be cost-effective.

For what it’s worth, the field of public health generally is considered to be a leader in developing metrics for success. My work on child survival in Africa and Asia was looked at by people in other disciplines as leading the way to establish the best practices for determining impact. Public health programs have done a fantastic job laying out the metrics for success and measuring them. They’ve done this far more than many other programs, again including police and fire. For this reason alone we should welcome this kind of Director and this kind of department into our city. It will set a standard that others have not been asked to follow.

Robb…

I consider that a fair response… I’m not singling out MH, as opposed to PD or FD… I agree that metrics should be applied to all municipal functions… but here, we have an implied “new function”… one not well defined…

And, “public health” is not = “mental health”… public health includes PW efforts in ensuring the potable water system, sanitary sewage system… it includes FD and PW responses to Haz Mat incidents in the roadway… public health includes Dr appts, treatment, etc., etc.

The “program” as revealed to date is very ambiguous unless one equates “public health = mental health incidents”…

I hope you’re not saying,

We should accept new initiatives merely as part of our community without questioning whether they’re having a positive impact for the amount of money that we spend on them.

As I said (now twice), one position proposed, is not an issue to me… the ‘program’ (as yet not fully defined) may be a slippery slope, fraught (potentially) with great costs, unclear effectiveness, duplication of effort, etc., and that is my only concern…

Bill, you act like there’s absolutely nothing happening in this domain, but in fact we are running a variety of programs already in the city. This is not new. We have programs that are designed to deal with a number of issues. None of the things I have raised represent new programming areas. I am really baffled about what the concerns are here in terms of lack of definition. Are people simply not paying attention to the things that are already happening in our city?

Could well be… lack of making it clear to general public… being retired for ~9 years, what I really recall of City efforts goes back that long… so, education as to “the things that are already happening in our city” would be good to publicize…

Still, gets to FTE’s… open, but skeptical… let’s leave it at that, as I have no ‘agenda’… and am not saying you do… but others may, one way or the other…