By David M. Greenwald

Executive Editor

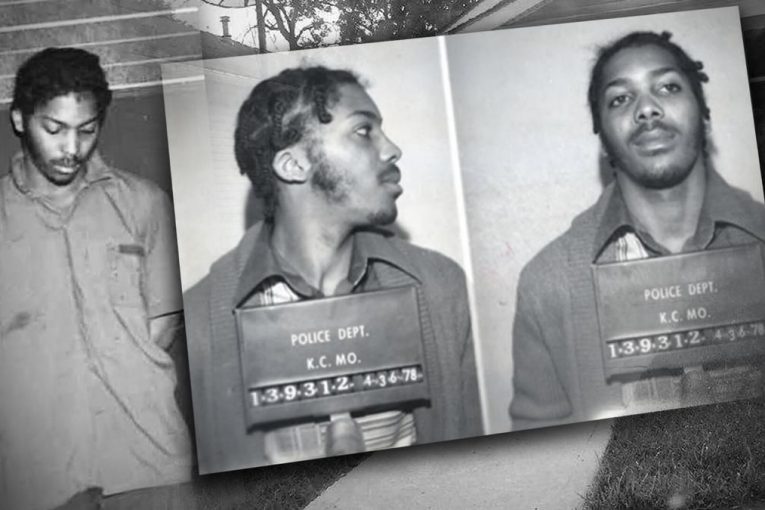

Kevin Strickland has spent more than 42 years in prison with all evidence, including the actual perpetrators and the sole surviving victim, believing he was wrongly convicted—but politics and arcane rules in the state of Missouri have kept him in prison.

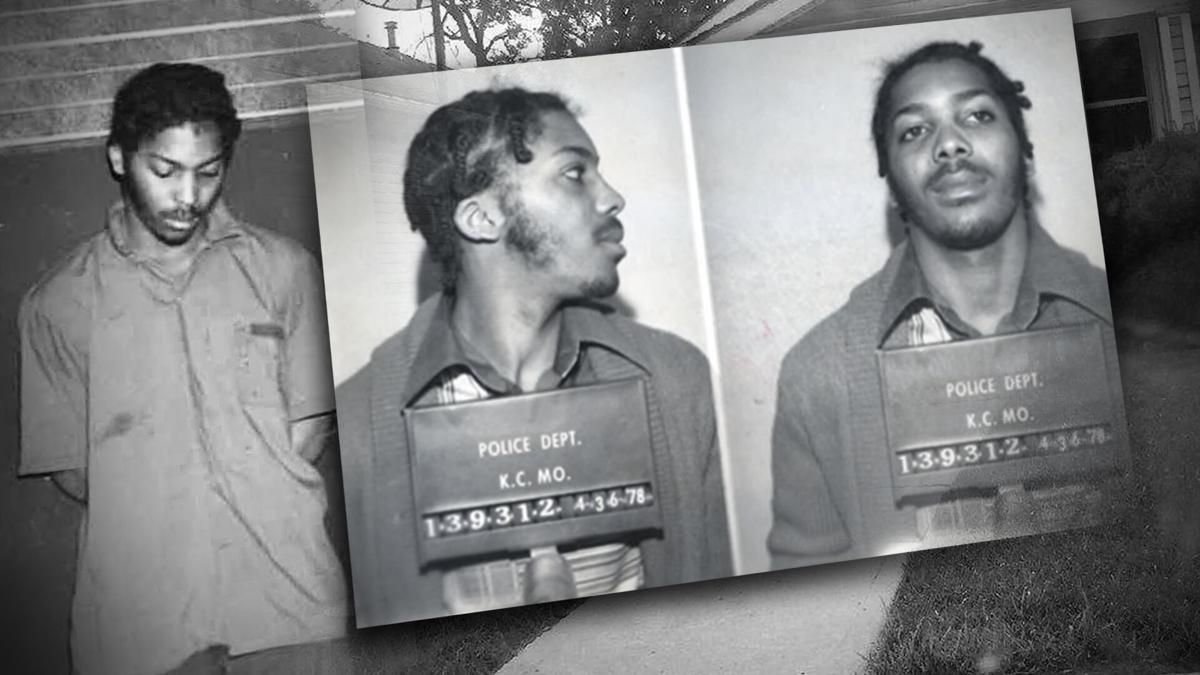

In July, Kenneth Nixon and Marvin Cotton traveled to Missouri to show their support for Strickland—whom even Jackson County prosecutors say is innocent of the triple murder from 1978 in Kansas City.

Why is he still in? Largely because there is an evidentiary hearing set for August 12 where the Missouri Attorney General will be arguing he should remain in prison. This despite the fact that Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker said her  office had concluded Strickland, who was 18 when he was arrested, is “factually innocent” in the shooting and apologized on behalf of their office.

office had concluded Strickland, who was 18 when he was arrested, is “factually innocent” in the shooting and apologized on behalf of their office.

Nixon, who was freed in February of this year after spending just under 16 years in prison, is stunned by this turn of events.

“It’s shocking that the justice system works the way that it does,” Nixon told the Vanguard in a recent phone interview. “You know, sadly, it’s not uniform anywhere. The laws that are being used in Michigan by our conviction integrity units don’t exist in some other states. Missouri is a perfect example of that, where the prosecutors have the authority to (put) you to death, but they don’t have the authority to get you out.”

Kenneth Nixon’s case was almost a classic example of what goes wrong in the system – starting with jailhouse informants.

“There was always a question of identity from the very beginning,” he said, explaining that they later found a memo through the appellate discovery process.

The case out of Michigan saw a situation where Nixon’s girlfriend was having an affair with one of Nixon’s close friends.

While this was happening, “someone set the house on fire and the police used our prior history of not getting along as a motive to say that I’d done it.” But almost from the start, homicide detectives questioned that finding.

The memo that only came up during the post-conviction process showed the detectives had considerable doubt about the veracity of the story fabricated by the jailhouse informant.

Nevertheless, Nixon received two consecutive life terms plus 40 to 60 years for four attempted murders.

When he read about Kevin Strickland and what he is going through, he wanted to do something about it.

“It’s painful to even think of four-plus decades of suffering for something that you didn’t do,” Nixon said. “The thought of him doing almost three times what I did—like, there’s times when my faith wavered, so I can only imagine how many times he has felt that way.”

He finds it crazy that the prosecutor “can take your life away, but he can’t restore it when there’s been a mistake.

“It’s crazy to think that this is okay in 2021. With all of the attention that’s being shined on criminal justice reform, this is still happening in parts of our country,” Nixon said.

Nixon is skeptical of the system. “We can get something completely wrong and potentially cause someone to die after being punished for decades for something that we now know that person didn’t do, and the Attorney General’s position is he missed his deadline. That doesn’t even make sense. Like, it’s just hard for me to comprehend that.”

Prosecutor Baker believes that Strickland is factually innocent and has agreement from federal prosecutors, Jackson County’s presiding judge and other officials who say Strickland should be exonerated.

They filed a motion in June but it was denied by the state supreme court.

Baker said, “We are disappointed. But we are pursuing all avenues of exoneration for Mr. Strickland.”

However the AG’s office believes that Baker and his office are mistaken. In a response brief, they argued the Jackson County Prosecutor’s Office has “studiously avoided, overlooked, misinterpreted, or misunderstood much of the evidence in Strickland’s case.”

The AG maintains that Strickland is guilty and pointed to police reports in which a witness said Strickland had allegedly offered the lone eyewitness to the murders money the day after the killings to keep “her mouth shut.”

However, that claim never came up during trial and Jackson County’s chief prosecutor said it is unclear why the prosecutors did not ask Harris about it on the stand.

For Nixon, he knows how Strickland must be feeling.

“I don’t think there’s an appropriate word to really describe that feeling,” he said. “It’s horrible to even to have to process that on a daily basis, because you have to look at, especially people like in he and I situation where you’re sentenced to life, you’re sentenced to die in prison for something that you didn’t do, but yet you’re forced to watch people that actually committed crimes that actually did harm, somebody go home on a regular basis.

“Sometimes multiple times a week. You watch those people go home after doing heinous things, but yet you’re forced to sit on the sidelines and watch that, and you’ve done nothing.”

He said he kept going, by “(n)ever wavering in his hope, not letting go of knowing that one day, my moment was going to come.”