by Kira Dunn

by Kira Dunn

Christopher Dunn just spent his 11,471st day locked in prison for a crime he proved he did not commit. In September 2020, a judge wrote in his order that Dunn is innocent. However, Dunn still languishes behind bars—because in the state of Missouri, innocence is not enough to free him.

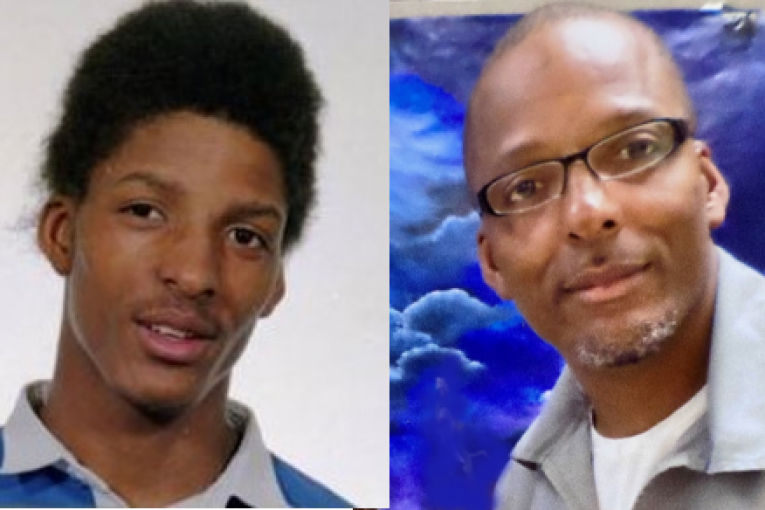

Arrested for murder at age 18, convicted at 19, and now nearly 50 years old, Dunn has always maintained his innocence.

On the cloudy St. Louis night of May 18, 1990, Christopher Dunn was in his mother’s kitchen on the phone with a friend while his family socialized around him. He hung up so that a visiting uncle could make a quick call before leaving. Dunn and his mother and sisters were walking his uncle outside to the car when they heard gunshots in the distance. The uncle left quickly, and Dunn’s mother shooed everyone back inside.

The police came looking for Dunn the following day and arrested him. He was held for 15 months in the city jail before his trial. His public defender, who spent about 20 minutes total with him before representing him in court, did not call his alibi witnesses, present phone records, test for gunshot residue, or conduct any other sort of crime scene analysis.

No physical evidence linked him to the crime. The prosecution had only the testimony of two young boys, aged 12 and 14, who said that Dunn shot at them and hit their friend as the three sat on a porch around midnight.

Both boys, now men, have recanted their testimonies and explained that they accused Dunn because they didn’t like him. Neither boy saw the person who fired shots from the dark, they admit. In exchange for their testimonies, both received generous deals on unrelated charges pending against them.

Now that its only evidence against Dunn was revealed as false, the State no longer has a case. A 25th Circuit judge agreed that is Dunn is innocent after an evidentiary hearing in which both recantations were presented, and an independent witness testified that it would have been impossible to see where the shots came from—much less who fired them. The friend on the phone testified that she was talking with Dunn moments before the crime took place.

In his ruling, the judge noted that Dunn clearly meets the standard for “freestanding” actual innocence—a claim that seeks relief based on newly discovered evidence.

Even so, he refused to free Dunn from prison, believing he was bound by Lincoln v. Cassady. In that ruling, the Western District Court of Appeals decided that Missouri prisoners who prove their freestanding innocence cannot be released—unless they are on death row.

Christopher Dunn was sentenced to life without parole plus 90 years. While some people might consider this a long, slow death sentence, Dunn is not a death row inmate.

Judge Hickle wrote, “Unless Lincoln is overruled or another division of our appellate court decides differently, controlling precedent would appear to limit freestanding claims of actual innocence to capital punishment cases.”

On August 31, the Missouri Supreme Court refused to review Dunn’s habeas petition, effectively closing the door to any relief in the state courts, and allowing the unconstitutional Lincoln v. Cassady ruling to stand. In a phone interview, Dunn reflected on the denial.

“I had hope,” explained Dunn. “I tried to give a chance to the Missouri judicial system, despite what I thought they might do to me. But I wasn’t surprised that they took the same stance against me as they did with Dred Scott.”

Dunn was referring to the case of Scott v. Sandford, in which an enslaved man won his freedom in court, only to have the decision reversed by the Missouri Supreme Court in 1854. The courthouse where Dred Scott was denied still stands in downtown St. Louis.

Dunn’s only hope for exoneration now lies with recent Missouri Senate Bill 53, which provides a path for prisoners who prosecutors believe to be wrongfully convicted. With the support of St. Louis’ top prosecutor, Kim Gardner, Dunn might have one more chance to avoid dying in prison. Gardner’s office is closely reviewing Dunn’s case.

“I had at this (evidentiary) hearing what I didn’t have at my trial. I had a defense … a lawyer who presented evidence to prove to the Court that I was innocent. It still wasn’t enough in Missouri. I’ve jumped through every hoop. I proved I was innocent. The Court said I was innocent. What do I do now?” Dunn asked.

Another question looms larger. If Missouri’s highest court is no longer willing to consider freestanding innocence cases, it instead will rely on Senate Bill 53. This puts tremendous pressure on individual prosecutors to determine if the accused should be exonerated. If not supported for some reason by the very offices that prosecuted them, will the innocent be condemned by the State of Missouri to an eventual lonely death behind bars?