By Gil Garcetti, Ira Reiner and Miriam Aroni Krinsky

In the 1980s and ‘90s, California embarked on a disastrous social experiment. Legislators embraced reactionary law-and-order policies that ratcheted up punishment in criminal cases. The negative impact of these policies overwhelmingly fell on poor, Black and brown communities. Sentence lengths and the corresponding cost to taxpayers skyrocketed, with California’s prison population ballooning from 23,000 in 1980 to more than 160,000 by 1999.

While the number of people behind bars has dropped since then, there are still more than 157,000 Californians under some form of supervision, costing the state more than $13 billion annually, with local jurisdictions spending billions more on jails, police and sheriff’s deputies. California’s addiction to incarceration has created a moral crisis and an economic sinkhole as well.

Proponents of “tough-on-crime” policies continue to sell the public a false promise that more punishment means more safety. But their math doesn’t add up. When California and other states reduced their prison populations over the last two decades, their crime rates declined to lows not seen since the 1960s. And despite fearmongering claims, there is no evidence that the recent increase in certain serious crimes — and in particular homicide — is associated with criminal justice reforms. (The increases occurred in places where reforms were embraced and where they were not.)

California and other states reduced their prison populations over the last two decades, their crime rates declined to lows not seen since the 1960s. And despite fearmongering claims, there is no evidence that the recent increase in certain serious crimes — and in particular homicide — is associated with criminal justice reforms. (The increases occurred in places where reforms were embraced and where they were not.)

Luckily, voters are recognizing that mass incarceration simply hasn’t worked. Our nation’s rate of incarceration — second to none — falls disproportionately on minorities, wastes taxpayer resources and doesn’t make us safer. The voters are bringing this understanding to the ballot box, electing a new generation of prosecutors in every corner of the country who are bringing big reforms, and big savings, to our communities.

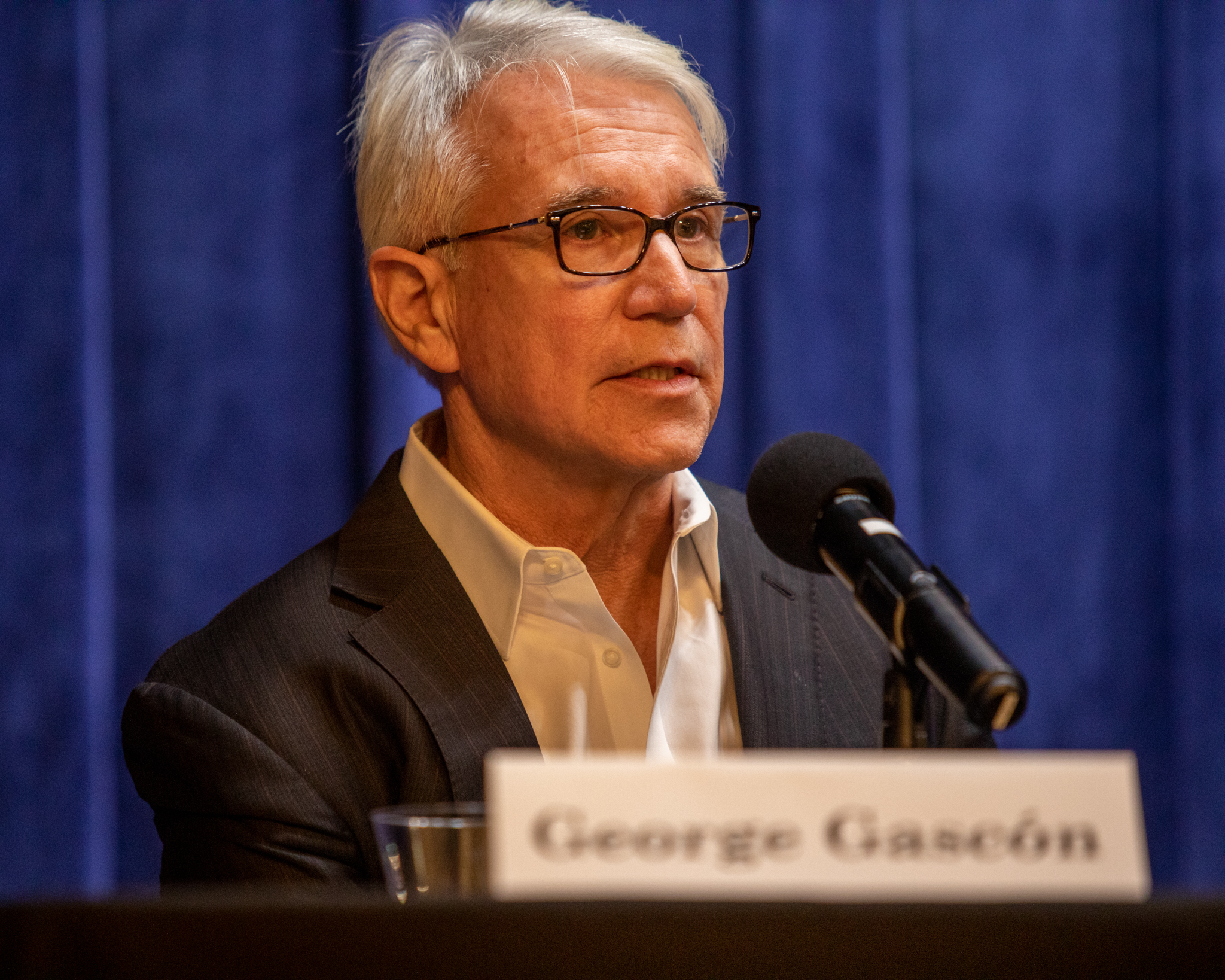

In America’s most populous county, Los Angeles Dist. Atty. George Gascón was elected in 2020 on a platform of common-sense justice reforms that emphasized rethinking when and if to pursue criminal charges and decades-long sentences. By his estimate, in his first 100 days alone, his policies would save taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars.

Most of the projected savings would come from eliminating the use of many sentencing enhancements. It’s within prosecutors’ well-established discretion to add extra time to standard sentences. According to the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, it costs taxpayers $103,498 to incarcerate an individual annually in California. So just one extra year for each of the 72,852 people currently serving a prison sentence lengthened by an enhancement would cost Californians over $7.5 billion. And more than 15,000 of these individuals are serving a sentence where the time added by enhancements is more than 15 years.

It’s not just that this is a lot of money, it’s that these billions of dollars are being spent on an ineffective response to crime. Research shows that excessive sentences may actually increase rates of reoffense, and therefore diminish public safety and create more victims of crime. In fact, people tend to age out of crime as they reach their 30s and 40s, so continuing to lock people up well into their 50s, 60s and beyond does not impact crime; it does, however, add significant costs as healthcare needs often increase with age.

Despite the astronomical costs to taxpayers, the lack of evidence that sentencing enhancements make us safer, and the support from Los Angeles voters to get rid of them, some are still digging in their heels to protect the status quo.

The California Court of Appeal is currently hearing a case in which a trial court denied a motion from Gascón’s office to dismiss and withdraw sentencing enhancements filed under the previous district attorney. And the Assn. of Deputy District Attorneys in Los Angeles County sued Gascón after he announced he would end the practice of charging and seeking sentencing enhancements.

Gascón clearly has the prosecutorial discretion to decide when to seek — or withdraw — sentencing enhancements, just as he and every other elected prosecutor have discretion to decide when and if to file charges. It’s the same discretion that was used for decades to add unnecessary years onto sentences and swell the prison population at great human and financial cost. Sadly, only now — when discretion is being used to undo that harm — is it being challenged.

That’s why dozens of bipartisan criminal justice leaders across the country have weighed in on these cases to ensure that prosecutorial discretion is protected and that these elected leaders have the ability to implement the changes they promised their communities.

Evidence-based policies like the ones Gascón is implementing in Los Angeles hold people accountable without relying on extreme sentences, and they save taxpayer dollars that could be invested in things that actually have an impact on crime, such as public health, housing, education and violence prevention. Those committed to the “tough-on-crime” policies of the past must recognize that more incarceration is not the answer, and that continuing to obstruct this new vision of justice only makes us all less safe.

Article originally published in the LA Times

Gil Garcetti is a former Los Angeles County district attorney. Ira Reiner is a former Los Angeles County district attorney and former Los Angeles city attorney. Miriam Aroni Krinsky is the executive director of Fair and Just Prosecution and a former federal prosecutor.