This report is written by the Covid In-Custody Project which partners with the Davis Vanguard to bring reporting on the pandemic in California’s county jails and Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) to the public eye. Visit our website to view and download our data on cases, testing, releases and vaccinations for incarcerated people and staff.

By Cassie Gorman (edited by Martin Sevcik)

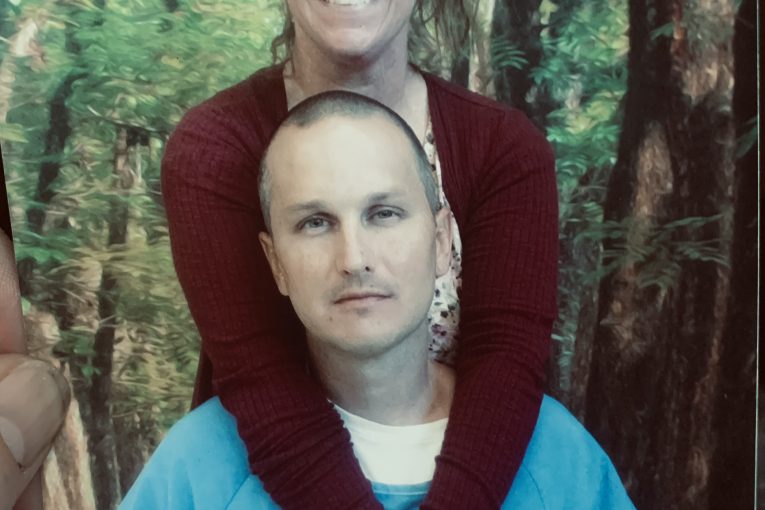

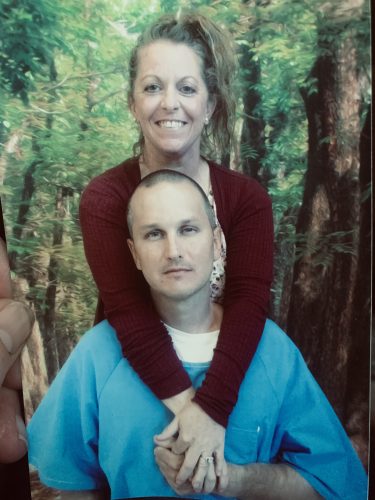

When Jill Engle found Scott Behnke’s profile on the website Write a Prisoner, she never expected to be anything more than friends. But after meeting in March 2021, the couple quickly fell in love, becoming engaged just six months later. They planned their wedding for Sept. 7, 2022 and patiently waited to tie the knot.

But just three days before their wedding, Behnke’s facility in Valley State Prison entered a two-week lockdown following a COVID-19 outbreak, canceling four of the couple’s planned visits – including their wedding date.

Over the past 18 months, the prison’s COVID-19 policies – from sudden lockdowns to physical contact moratoriums during visitation – have strained Behnke and Engle’s relationship. The couple reached out to the Covid In-Custody Project expressing frustration at the CDCR’s COVID-19 policies.

“I do not have covid but am being emotionally and mentally tortured and my relationship with my wife subjected to unimaginable strain because of an absolutely ludicrous policy,” Behnke writes. “I cannot begin to describe how hostile I feel inside towards this system. How heartbreaking it is to have to console my fiance over the phone because they destroyed her wedding. What sick sort of person does this?!”

Under the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s Roadmap to Reopening guide, a facility enters lockdown if three or more people in that facility test positive for COVID-19. Because facilities often span several housing units, Behnke is currently under lockdown even though the three individuals who tested positive reside in a separate building.

Engle can visit Valley State Prison once Behnke’s facility exits “outbreak phase” and enters into “open phase” – defined as having no COVID-19 cases for at least 14 days. Months of sporadic lockdowns and her wedding’s uncertain future have greatly affected Engle’s mental health.

“My feelings were telling me if this Covid stuff continues and ‘maybe you’ll have a visit maybe you won’t,’ I felt like I don’t know if I can do this for a couple more years because it is too emotional for me,” Engle explains. “But when you tell someone that you love them, and you want to spend the rest of your life with them, that’s through the good times and the bad times… It’s been difficult but we take one day at a time. That’s all we can do.”

In addition to lockdowns, other pandemic-related policies have strained their relationship, they claim. While hand holding, brief embraces and kissing are permitted during visitations under California Code of Regulations, Title 15, Section 3175, pandemic-era policy changes have barred Behnke and Engle from making any physical contact during visits.

The couple is required to stay six feet apart during visits and wear masks. During one visit, Behnke put his hand on Engle’s back while they were walking, and correctional officers promptly threatened to terminate their visit. Correctional officers have threatened to file CDCR form 115 if Engle makes physical contact with his fiancé. This disciplinary write-up would compromise his chances at parole.

Double standards exacerbate Behnke and Engle’s frustrations. While the incarcerated population and staff were both required to wear masks, Engle watched many correctional officers violate this rule. Behnke feels these mismatched policies are used to control incarcerated people, rather than to maintain health and safety in prison facilities.

“The policies are designed to create a culture of pain, heartbreak, disruption of the family dynamic, anger and hopelessness in the inmate population,” writes Behnke, who believes that access to visitation can boost morale and break the cycle of incarceration. “The world has moved on past the Covid hysteria, the CDC has openly stated that these heavy handed tactics are unnecessary. While the world moves on we suffer. Out of sight out of mind”

The couple’s experiences also reveal some unintended consequences of the COVID-19 policies. For example, incarcerated individuals must test for COVID-19 in order to receive visitors. If they test positive, their entire cell must quarantine, a process many want to avoid.

“There are guys who are refusing visits because they are scared, physically being intimidated into not testing by their podmates,” Behnke writes. “People have been beaten up for testing. Whenever we come off lockdown we have staff or inmates being beat up. The prison is erupting into 1980’s style violence.”

Behnke has seen this firsthand; he reports one of his seven cellmates intimidated him, although this experience did not deter him from testing.

After a year and a half of turmoil, the couple hopes making their story public will encourage others to take action and compel change in the CDCR. If an individual has not been directly exposed to COVID-19, Engle and Behnke believe their right to visit should not be stripped away. Ultimately, the couple believes the current policies stem from a pattern of abuse and neglect of the well-being of incarcerated people.

“There is a sickness here and it is not Covid,” Behnke writes. “It exists in the hearts and minds of CDCR staff and policy makers… COVID-19 is the new excuse to emotionally terrorize the population and their family’s and break our bonds.”

Note: On Sept. 7, 2022, CDCR guidelines regarding physical contact during visits were reverted to pre-pandemic standards. Further, masking guidelines have been relaxed for staff and incarcerated people.