by D. Razor Babb

You can’t have a meaningful discussion about social justice, crime, and public welfare without examining the issue of mass incarceration. Public outcry for tougher laws, longer sentences, more prisons is being driven by forces contrary to our better human nature.

Fear-mongering, political discord, and extremist rhetoric threaten to tear apart the fabric that binds this democracy, and is antithetical to building a better, safer  society. When we turn our backs to the harms we’re creating by our willingness to trample on others’ God given rights to freedom, equality, and to be treated with decency as human beings, we’re ignoring our better judgment and going against what is right.

society. When we turn our backs to the harms we’re creating by our willingness to trample on others’ God given rights to freedom, equality, and to be treated with decency as human beings, we’re ignoring our better judgment and going against what is right.

The disparity in the numbers of those being locked away in this country’s penitentiaries should tell us something. This dynamic is borne of racial, class, and cultural bigotry and prejudice, and is so inbred in American culture that we accept it without question.

I call it, “The Mockingbird Syndrome.” In Harper Lee’s award-winning bestseller, To Kill a Mockingbird, defense attorney Atticus Finch defends a Black man accused of raping a white girl. The story is set in a small, Southern town in the 1930’s.

As the story develops and testimony of all the parties is presented in a packed courtroom, it becomes obvious that the accused is not the only one on trial, but it is the entire town and its Draconian, unjust, and heinous prejudices as well that are being judged.

Finch quietly and methodically shreds the main witnesses’ testimonies, and brings to light the true story behind what resulted in an innocent man being charged. In his closing argument he asks the all-white jury why a young, cloistered, ignorant white girl would willingly claim such an allegation that would surely send a man to prison, or worse.

The ugly nature of what truly might occur was obfuscated; however the specter of lynching lingered in the drama forebodingly.

Finch explains that the reason is as insidious (to the alleged victim) as the crime of which his client has been accused. It is the girl’s guilt and shame for kissing a Black man, and being caught in the act by her racist, intolerant, abusive father. That guilt, and the shame she’d face in the eyes of the entire town triggered an explosion of self-denial, justifying lies, accusations, and blaming so intense that it overwhelmed the truth and overrode decency and humanity.

Even in the face of overwhelming evidence of innocence, Tom (the accused) was convicted and a method of execution was (conveniently) contrived to enable retribution for sins he was not guilty of, but for which the entire town bore responsibility.

In an insightful overview of how our society actually creates more crime and criminals via a tunnel vision focus on a hardline approach to crime and punishment, Marshall Project founder Bill Keller writes in What’s Prison For? “…most of the people who end up in prison, their crime was more than a random event. It had roots and a context.”

He quotes James Forman, Jr., from Locking Up Our Own, his Pulitzer Prize winner on crime and punishment in Black America: “The system is racist, and … It isn’t enough to have explained to people that the system is racist. It’s important, but, when crime and violence are rising, the ‘and’ becomes front and center on people’s minds.”

Bruce Western of Columbia University in Punishment and Inequality in America points out, “Mass incarceration flows along the lines of social and economic inequality. Its characteristics are massive racial and class inequality. It’s a system that concentrates all of its effects on low income communities of color.”

Many experts agree that mass incarceration is the foremost civil rights issue of the day.

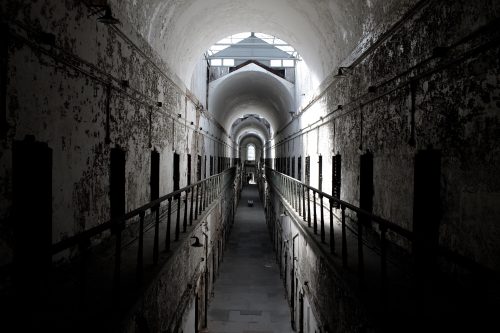

Thus, The Mockingbird Syndrome, with we as a society turning our backs on the brutality and inhumanity going on behind the walls and fences of our prisons.

And behind the doors of our nation’s courtrooms.

Locking people away based on racial and cultural bigotry and prejudice, while ignoring the core reasons behind criminality and an unwillingness to face our guilt and shame over our own prejudices—justifying our ignorance, brutality, and callousness to our fellow man is our generational original sin.

Where we go from here determines our legacy.