How The Digital Search Tool Allows Them To Critically Evaluate Mass Incarceration, The 1619 Project, Youth Offender Jurisprudence, Abolition Versus Reform, And Qualitative Studies Concerning The Efficacy Of Carceral Self-help Programs

Most people don’t know that throughout California’s network of prisons community college enrollment is free, or that incarcerated learners use WiFi-enabled laptops to access a modified version of Canvas in order to submit their assignments. Our journalism work largely depends upon our use of the partially firewalled EBSCO tool that enables students to access portions of the database’s inventory of published journals, book reviews, research papers, and law review articles concerning all manner of subject matter. In a setting where novel stimuli is scarce and access to accurate information is policed, any semblance of what might be considered academic liberty is cherished. We recently convened a small gathering of incarcerated learners enrolled in different college degree programs at Valley State Prison (VSP) to find out how EBSCO is democratizing knowledge.

We kicked off the EBSCO roundtable in the rear of the VSP law library by centering historian Elizabeth Hinton’s groundbreaking book From The War On Poverty To The War On Crime: The Making Of Mass Incarceration In America, made available to us by the Mellon-funded Freedom Library. The most comprehensive book review of Hinton’s work comes in the form of a 2017 Texas Law Review article authored by Jonathan Simon, the Adrian A. Kragen Professor of Law and Faculty Director of the Center for the Study of Law & Society at U.C. Berkeley, titled “Is Mass Incarceration History?”, which described how Hinton’s thesis relied upon never-before-seen National Archive material and is “the most telling account yet of this new history of the American carceral state.”

Thanks to EBSCO, we were able to chew on two attempted take-downs of Hinton’s work authored by Adaner Usmani, who, via two works featured in the Jacobian Foundation’s journal Catalyst, titled “Did Liberals Give Us Mass Incarceration?” and “The Economic Origins Of Mass Incarceration,” challenged Hinton’s denial that a real rise in crime fed into the politics of punishment, that racism accounts for discussions of Black criminality, Hinton’s dating of the punitive turn to policies whose impact on incarceration Usmani’s argues is unproven, and the evaluation of these policies by the standards of an implicit prison abolitionism. While agreeing that Hinton was right to deem liberals and the Democratic Party culprits of the punitive turn, Usmani took issue with Hinton’s failure to cite mortality statistics reflecting how the homicide rate almost doubled between the early 1960s and 1970s, arguing that when crime did rise, it was concentrated in Black communities, which liberals paid attention to because their constituents decried it.

If the rise in violence was real, and mass incarceration numerically reflected a rise in class disparity owing to most prisoners being convicted of violent and property crimes – not drug crimes – then, as Usmani argues, the concentrated poverty and crime in Black neighborhoods that elicited a liberal response opting to use police and prisons instead of social reform measures was rational. If mass incarceration was a system of race-based social control, why did White incarceration rates increase as rapidly as Black between 1850 and 1950, while the probability of Black college grads going to prison halved after 1990? In 2017, a year after Hinton’s book came out, according to an IPUMS Census sample, a White high school dropout was fifteen times more likely to be in prison than a Black college graduate. Needless to say, as a curious captive audience, Usami’s critiques gave us a counternarrative supported by alternative facts worthy of probing.

Skrybe, who told us his world view had been shaped most by having read Nikole Hannah-Jones’ The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, became, as he said, “shook,” by having read the American Historical Review’s “The 1619 Project Forum,” which presented nineteen scholars addressing the most polarizing elements of the original work that faced criticism for what was termed interpretive overreach and factual slippage. “The Forum challenged the entire central thesis that slavery was the cause of the American Revolution, and then,” he said excitedly, “the journal invited the New York Times Magazine editor in chief to respond to those critiques, giving them the final word. It was cool to see the back and forth.”

He found James Oakes’ essay in Catalyst, titled “What The 1619 Project Got Wrong,” which cited “egregious factual errors” within Jones’ work and rebuked what he called the “utter unoriginality of its claim to have discovered the historical significance of the year 1619,” at least provoking, if not definitive, owing to how difficult it is for incarcerated folks to discern fact from falsehood absent resources.

Skrybe said “as much as I was moved by the book and its incredible claims, which for me were original to my ears, it hit me different to read the criticisms and learn these claims weren’t necessarily new, or in some cases were credibly disputed. That gave me pause, but made me evermore curious.” Hungry for more, he dug up Peter A. Coclanis’ “Capitalism, Slavery, and Matthew Desmond’s Low-Road Contribution to the 1619 Project” in Independent Review, which assailed the New History of American Capitalism (NHAC) and its Ivy League contempt for capitalism, which he claims seeks to contextualize it as illiberal and dependent upon slavery and unfree labor. Eager to find more to read, Skrybe said “I’m hooked on history, because there is so much to unravel between the origins of banking, agriculture, slavery, and politics that will occupy me for years to come, for sure.”

Lefty talked about how reading Laura S. Abrams’ Marquette Law Review article titled “Growing Up Behind Bars: Pathways To Desistence For Juvenile Lifers,” “gave me all the laws passed in California that impact youth offenders since 2012 in one place and articulated a study that looked at males who committed homicides while age twenty or under who served indeterminate sentences ranging from 21 to 44 years before becoming resentenced and paroled. Professor Abrams really captured the reality of what happens when a lifer reconciles trauma, transforms morally, and finds purpose in living a hope-filled existence.” Serving LWOP as a youth offender in California, Lefty can’t access a parole hearing or petition a court to review his rehabilitative growth, though he and other LWOP youth offenders like him are the specially-trained Mentors delivering the state-approved curriculum to the youth offenders serving life terms who can. The role models aren’t rewarded.

“I found a concise breakdown of the People v. Hardin decision in Probation and Parole Law Reports,” Lefty explained, “challenging the youth offender parole statute as unconstitutional on the basis it excluded similarly-aged youth offenders serving longer terms of LWOP. Though I disagree with the state’s Supreme Court’s ruling, which reversed a favorable Court of Appeals decision, the final decision held that the rational basis review standard is necessarily deferential, meaning LWOP-worthy offenses are uniquely serious, apart from whether or not sentencing disparities for similarly-aged cohorts of youth offenders with equal claim to the mitigation inferences stemming from brain science tied to age might appear inequitable. The decision puts the burden on the legislature to address those of us between the ages of 18 and 25 who make changes during our confinement. If youth offender lifers get parole review at year 15, 20, or 25, is it not reasonable to give a youth offender serving LWOP review at year 25, 30, or 35?”

For Terell, who devours abolition content, Angela Davis’ Are Prisons Obsolete, Doran Larson’s Abolition From Within: Enabling The Citizen Convict in Radical Teacher, Allegra M. McLeod’s UCLA Law Review article “Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice,” Dorothy E. Roberts’ Harvard Law Review Forum article “Racism, Abolition, And Historical Resemblance,” and Amna A. Akbar’s Yale Law Journal article “Non-Reformist Reforms and Struggles over Life, Death, and Democracy,” represent a canon of must-reads that exist at all “because of EBSCO. You can’t get this material in the law library, access it from the facility Lexis-Nexis, and nobody can afford to subscribe to law review journals.”

Though the reading can be “staggering” Terrell says, “this is the best writing and argumentation on the planet, so if you want to understand the meat of anything, avoid the fluff of opinion, and dig into the substance of an issue, law journals deliver. For me, nothing speaks more to the origins and purposes of the structural use of state power concerning the carceral state than the works of thinkers who, like Angela, targeted a goal of system change; who, like Doran, articulated a convict-citizen activist state of being built on community building that resists the civil death the PIC intends; and like the rest, who intellectually wrestle over the doable versions of abolition and the utility of reform. It’s thrilling to read it all, think about it, and have opinions about the things these brilliant people are publishing about the world we inhabit. We wish they could travel here, do a workshop, and stir their fingers through our thought pool. EBSCO has delivered them all to me through my laptop – its incredible how beyond prison my mind has been able to travel because of this tool.”

Scott chases studies that support the efficacy of arts-based carceral programs of all types. “The Journal of Corrections Education paper by Danielle Maude Littman titled ‘Prison Arts Program Outcomes: A Scoping Review’ covers most of it,” he said, “from theater, dance, music, writing, visual art, and literature, going back forty years. It’s all there. The data supports both the cost-effectiveness and facility safety justifications for why arts programming should exist. When people gather to create, they build community. It makes the prison a safer and less volatile place when people collaborate.”

An avid musician, Scott cited “a drumming study out of Israel by Moshe Bensimon, a Criminology professor, titled “Drumming Groups For Incarcerated Individuals In A Maximum-Security Facility,” published in the International Journal of Community Music which demonstrated how structured group drumming using a djembe promoted stress management, anger dissipation, and emotional non-verbal connection with others tied to matching rhythm and timing. That study motivated me to take a djembe class here.”

Scott told us he “found a piece in literature titled ‘A Bridge Across Our Fears: Understanding Spoken Word Poetry In Troubled Times’ by Jen Scott Curwood that cited other studies and described concepts like agency, a culture of listening, counternarratives, discursive learning spaces, radical classrooms, witnessing, and cited case studies of young poets voicing their work, which inspired me to think about how much there is to do here, right where we are. The convict voice is largely ignored, unless specifically studied, so, like how Professor Jeffrey Ian Ross writes about, it’s on us to do our research, become informed, and pivot into our activist Convict Criminology roles and project our voices, our art, our literature, and our stories into the free world. We are here, but EBSCO lets us be everywhere. Its the best portable educational tool we have.”

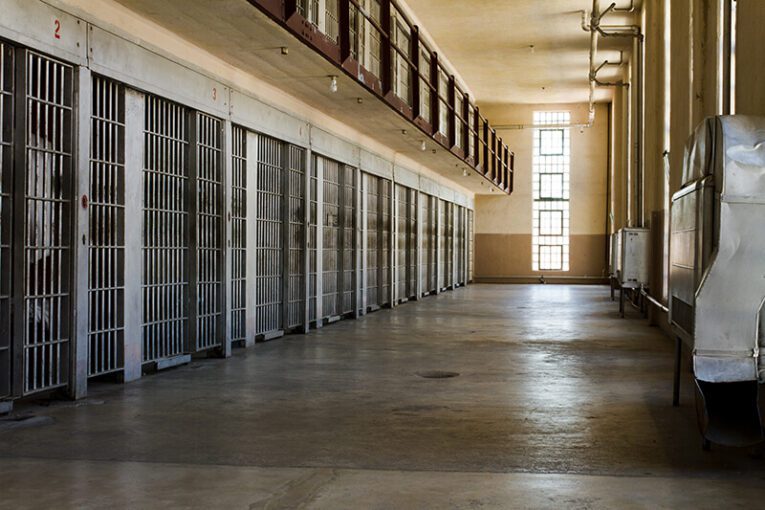

Prison robs you of your first name and hands you a number. You learn to strip, squat, spread yourself and cough on command, without hesitation. You become accustomed to the horrible food, the foul waves of stench, and the intruding sounds of human activity that never give you solace or silence. Your mind races against itself through mazes of memories, trauma, and regrets, while time warps into whatever possibilities your hopes and imagination can construct.

The TV, the radio, and the newsfeed on your DOC-issued tablet usually encompass the totality of sources of information about the world you gain access to, apart from books and magazines mailed to you, provided you have somebody willing to play librarian. But like Donald Rumsfeld used to say from the White House Press Room, the “known unknowns” keep reminding us that we don’t know what we don’t know.

Censorship blunts truth and retards knowledge. For us, society’s zombified shelf-dwellers, this EBSCO tool is like being able to use the Force to extract knowledge through a secret black hole that defeats the forcefield of censorship the Death Star has our colony encircled by.