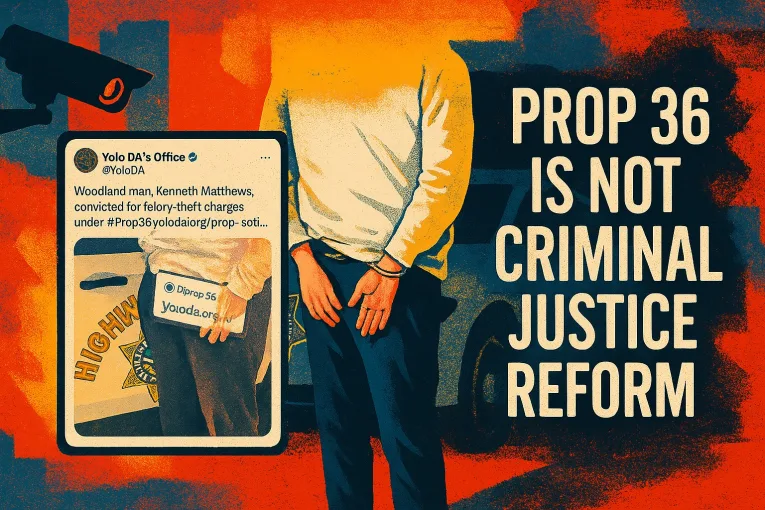

This week, the Yolo County District Attorney’s Office issued a press release touting the conviction of Kenneth Matthews under Proposition 36—a newly-enacted voter initiative aimed at cracking down on so-called “serial” retail theft.

The DA’s release proudly announced the use of its “FastPass” program, highlighting Matthews’ no-contest plea to several felony theft charges and his impending sentence of over three years in county jail.

For proponents of Prop 36 and the DA’s rhetoric-heavy crime control policies, this might look like a victory. The press release reads like a campaign ad: the DA name-checks Prop 36, appeals to voters’ sense of righteous indignation, and praises the “will of the people” while reinforcing his office’s role as an enforcer of accountability.

But behind this media-ready moment lies a more troubling truth: Prop 36 and its enforcement mechanisms represent a return to punitive policies that do little to address the systemic drivers of retail theft, let alone prevent future crime.

Matthews is, by all accounts, a person with a long history of low-level, non-violent theft and fraud offenses. His most recent charges include “ticket-switching” —substituting barcodes on expensive merchandise with cheaper ones—and use of stolen credit cards to make modest purchases. While this behavior is unquestionably illegal and frustrating for businesses, it is also deeply familiar to anyone who’s worked in or reported on the criminal legal system.

These are crimes of desperation, addiction, or untreated mental illness. They are not armed robberies or violent home invasions, yet they are increasingly treated as though they are.

Matthews’ case is now being held up as a success story under Prop 36—a law that critics warned would reintroduce felony-level incarceration for repeat shoplifters and erode decades of reform under previous initiatives like Props 47 and 57.

Prop 36 does precisely what its backers claimed it would: it takes someone like Matthews, tallies up his priors, and transforms him from a nuisance into a felon eligible for serious prison time.

But what the DA won’t tell you is that Matthews’ three-year, four-month sentence will be served in local prison—a term that became legally possible only after realignment, a reform designed to reduce the state prison population by shifting inmates to local jails.

That means Matthews won’t be shipped off to San Quentin with its state-of-the-art programming; instead, he’ll be warehoused in a county facility ill-equipped to provide meaningful rehabilitation, vocational training or education, or mental health care.

His odds of reentering society with the tools to avoid reoffending? Slim to none.

Prop 36, in practice, is a throwback to the failed policies of the 1990s—policies that led to California’s mass incarceration crisis in the first place. It uses the language of “accountability” while ignoring the root causes of theft and poverty. It appeals to voter frustration while making no investment in solving the underlying issues that drive people like Matthews to engage in retail theft.

There’s no denying that theft has become a visible issue in many communities. Retailers are understandably alarmed by losses, and voters are frustrated by a perceived lack of enforcement. But the response from elected prosecutors like Jeff Reisig has been to double down on the criminalization of poverty.

The DA’s “FastPass” program, which allows big-box stores like Home Depot and Target to file cases directly with prosecutors, exemplifies this shift: corporations now have a direct pipeline to the criminal legal system, bypassing the typical investigatory safeguards that ensure fairness and proportionality.

The Matthews case demonstrates how Prop 36 enables this dynamic. In a span of just a few months, a man engaged in ticket-switching and minor fraud offenses suddenly finds himself facing multiple felony counts and a multi-year sentence—not because the nature of the crime changed, but because voters were sold a narrative that repeat shoplifters are dangerous threats requiring swift and severe punishment.

The real danger here isn’t Matthews. It’s the normalization of harsh sentencing for low-level offenses, the creeping rollback of reform, and the quiet empowerment of corporations in the criminal legal process.

The retail theft “crisis” has been blown out of proportion by media fearmongering and political opportunism. Data from across the country shows that retail theft rates are not skyrocketing—they are uneven, localized, and often exaggerated. And even where increases are real, they are rarely linked to organized crime or violence. Instead, most thefts are committed by individuals like Matthews—struggling with economic insecurity, housing instability, or untreated addiction.

And yet, instead of investing in community-based solutions, economic supports, or restorative justice programs, the state has opted for punishment—because it’s easier to prosecute a person than fix a broken system.

The press release from the DA’s office makes one thing abundantly clear: this isn’t about justice. It’s about optics. By emphasizing the will of voters and linking the conviction to Prop 36, DA Reisig seeks to validate a punitive model of prosecution that has already failed California once. He packages incarceration as accountability and conflates repeat petty theft with organized criminal conspiracies. And in doing so, he shores up a narrative that undermines public trust in reform.

What happens next is predictable. Matthews will serve his sentence in local custody. He’ll be released into a community where his felony convictions make housing and employment nearly impossible. He’ll likely struggle with the same issues that led him to shoplift in the first place. And when he reoffends—as many do when returned to the streets without support—he’ll become another cautionary tale trotted out to justify the next crackdown.

The cycle continues, and the system spins on.

California has spent the better part of the last decade trying to undo the worst excesses of the “tough on crime” era. We’ve passed reforms to reduce incarceration, invested in alternatives to jail, and sought to treat low-level offenses with proportionality. Prop 36, and the DA’s celebratory press release, represent a dangerous reversal. They are signals that we are once again confusing punishment with progress.

If California wants to reduce retail theft, we need to stop feeding the incarceration machine and start asking the hard questions: Why are so many people living on the margins? Why is mental health care still inaccessible to thousands? Why are corporations the only ones with a FastPass to the justice system?

Until we answer those questions, Prop 36 will do little more than shuffle more poor people into jail cells—and call it justice.

“a newly-enacted voter initiative aimed at cracking down on so-called “serial” retail theft”

There’s nothing “so-called” about it.

Is Reisig going to run for State Attorney General?

These kinds of posts would make it difficult in California: https://davisvanguard.org/2025/02/reisig-posts-rant-on-instagram-account-tying-usaid-grants-to-campaigns-against-him/

“Is Reisig going to run for State Attorney General?”

We can only hope.

Can you imagine how that would explode the heads of all the people with RDS, Reisig Derangement Syndrome.

Serial thief or serial incarceration that is the question.

The third option is to break the cycle and that’s not done through incarceration