In February 2025, the United States Supreme Court did something rare: it vacated the conviction of Richard Glossip, a man who had spent nearly three decades on Oklahoma’s death row. In a unanimous decision, the Court cited grave prosecutorial misconduct — including the state’s failure to disclose evidence that could have discredited its star witness — and ordered a new trial.

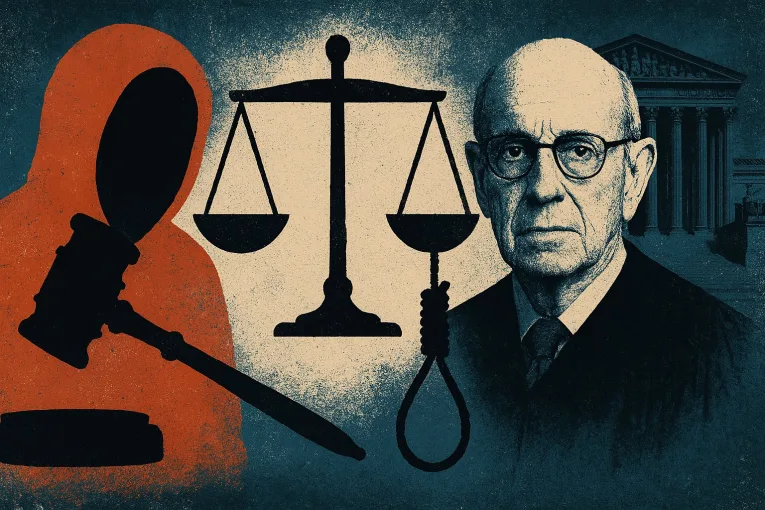

The ruling shocked many observers. Yet for those familiar with the long, tortured history of the Glossip case, the only surprise is that it took this long. In fact, the most astonishing thing about the Court’s decision is how squarely it confirms what Justice Stephen Breyer warned us about nearly a decade ago: that the death penalty in the United States is so deeply flawed, so infected with error and arbitrariness, that it has become unconstitutional.

Breyer’s warning came in 2015, in a dissent in Glossip v. Gross, the case that first catapulted Richard Glossip into the national spotlight. At issue then was Oklahoma’s use of midazolam, a sedative implicated in a series of botched executions. The Court, in a narrow 5–4 decision, allowed the state’s lethal injection protocol to stand. But Breyer, joined by the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, went further than simply objecting to a specific method. He challenged the death penalty itself.

Breyer’s dissent was sweeping and increasing prescient. Citing decades of research, legal precedent, and empirical data, he argued that capital punishment had become incompatible with the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. It was not only morally questionable, he wrote, but irredeemably broken — plagued by “serious unreliability,” racial and geographic bias, extraordinary delays, and profound arbitrariness.

At the time, Breyer’s critique was seen as an outlier— a principled but lonely voice on a Court still largely committed to capital punishment. But fast-forward ten years, and Glossip’s own case has become the very embodiment of the systemic failures Breyer described.

Glossip was convicted of orchestrating the 1997 murder of Barry Van Treese, based almost entirely on the testimony of Justin Sneed — the actual killer, who received a plea deal to avoid the death penalty in exchange for implicating Glossip. There was no physical evidence tying Glossip to the crime.

Over the years, lawmakers, legal experts, and journalists have repeatedly raised doubts about his guilt. And yet Glossip came within hours of execution on multiple occasions, enduring the psychological torture of preparing to die while maintaining his innocence.

The trauma Glossip endured was not an aberration — it is the norm in America’s death penalty system.

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor has noted, the Eighth Amendment guarantees that no one should be subjected to “searing, unnecessary pain before death.”

But Glossip’s case reveals a different kind of searing cruelty: the relentless psychological toll inflicted by a legal system more interested in finality than fairness.

In his 2016 book Against the Death Penalty, Breyer elaborated on the views expressed in his dissent.

He cited growing evidence that innocent people had been executed, including those exonerated only after posthumous review. He pointed to the fact that the death penalty is sought almost exclusively in a handful of jurisdictions — a reflection not of national consensus, but of local prosecutorial zeal.

And he warned of the Kafkaesque delays that render the promise of justice hollow. Of 183 people sentenced to death in 1978, Breyer observed, only 21 percent had been executed 35 years later; the rest had their convictions or sentences overturned, died in prison, or remained stuck in limbo.

These were not statistical quirks. They were the predictable outcomes of a system whose foundations had eroded.

Breyer drew heavily from the Enlightenment philosopher Cesare Beccaria, who wrote that “every punishment which is not absolutely necessary is a cruel and tyrannical act.”

The Constitution, Breyer argued, demands not only justice in theory, but in practice. And when the death penalty is applied with arbitrariness akin to “being struck by lightning,” as Justice Potter Stewart once wrote, it cannot be reconciled with that mandate.

Breyer’s critics — including Justices Scalia and Alito — often point to originalism, arguing that because the Constitution’s drafters accepted capital punishment, it must remain constitutional.

But Breyer, in the spirit of Jefferson, rejected this static view of law. “We might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy,” Jefferson once wrote, “as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors.”

In other words, the Constitution must evolve as our understanding of justice evolves. And what we now understand is that the death penalty cannot be administered fairly, consistently, or reliably.

And yet, even as Breyer’s warning grows more prescient, the machinery of death continues to turn. The state of Oklahoma was prepared to execute (despite bipartisan believe in Glossip’s innocence) Glossip despite the overwhelming evidence of a wrongful conviction.

It was only the Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling — driven by a level of prosecutorial misconduct too egregious to ignore — that temporarily halted the gears.

But how many others have not been so lucky?

This is what Breyer meant when he spoke of “serious unreliability.” It is not just the possibility of error — it is the reality of it. Over 190 people have been exonerated from death row in the modern era. Others, we now know, were likely innocent but executed anyway. There is no way to fix such a system. The only moral and constitutional response is to end it.

It is worth noting, too, that Breyer’s critique was not purely legalistic. It was rooted in human experience. He was deeply attuned to the way death row isolates, dehumanizes, and destroys. He saw how race and poverty dictate who receives the death penalty — how a Black defendant accused of killing a white victim is statistically far more likely to be sentenced to death than a white defendant who kills a Black victim. He recognized that the death penalty’s greatest defenders often turn out to be the same voices that champion “law and order” without grappling with the law’s own fallibility.

And still, nearly a decade later, the Supreme Court has refused to directly confront these problems. The recent Glossip ruling is a narrow procedural victory — one that does nothing to abolish the death penalty or address its underlying failures. It is a win for one man, but it leaves the system intact.

As Breyer wrote, quoting Justice Harry Blackmun: “I shall no longer tinker with the machinery of death.” The time for tinkering has passed. We must now ask ourselves what kind of justice system we want to preserve — one that enshrines fairness and dignity, or one that permits irreversible error and state-sanctioned cruelty?

The answer should be clear. And yet political expediency, cultural inertia, and misplaced trust in flawed institutions continue to prop up a punishment whose time has long passed.

The Supreme Court’s decision to vacate Glossip’s conviction should have been the beginning of a reckoning. Instead, it is being treated as an anomaly. But it is not. It is the rule — merely the first time the Court has chosen to acknowledge it.

Breyer saw this coming. He saw the impossibility of reconciling our evolving standards of decency with a punishment rooted in retribution and error. He saw that the death penalty does not serve justice, but undermines it.

The machinery still turns. But the gears are grinding down.

We should not wait for another Richard Glossip — another near-execution of an innocent person — to admit that the system is broken. It is long past time to do what Justice Breyer, Justice Blackmun, and so many others have urged us to do.

We must dismantle the machinery of death before it claims again what it cannot return.