In two weeks, Laurese Glover will join us for our 10th annual Vanguard fundraiser. The keynote speaker is Mark Godsey, the Director of the Ohio Innocence Project.

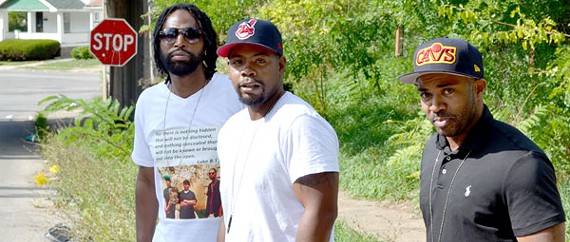

Laurese Glover, along with Eugene Johnson and Derrick Wheatt, was part of the East Cleveland 3, wrongly convicted for a 1995 murder and spending 20 years in prison for a crime he did not commit.

“At each step I always kept thinking, ‘OK, the adult court will get it right. We got a better chance than the juvenile court,’ and then we got convicted,” Glover said last year. “Then I thought, ‘OK, the appeals court is going to get it right.’”

Their conviction was centered around a single eyewitness testimony—which the witness, a young woman, 14 at the time of the murder, later recanted.

But the courts did not get it right—eventually they got their convictions overturned and the case dropped with the help of the Ohio Innocence Project.

Glover, along with Mark Godsey, will be the headlining speakers in two weeks—the event is now on Zoom because of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Variable rate tickets are available – here).

As we continue our nation’s racial reconciliation, it is important to understand that racial disparities permeate the entire criminal justice system. Wrongful convictions are no different.

A perusal of the list of wrongful convictions certainly uncovers an alarmingly high number of people from all races and ethnicities—but it is easy to underestimate the huge racial component of wrongful convictions.

For the past two weeks we have been running a series of articles highlighting the wrongful conviction cases identified by the Brooklyn Conviction Review Unit.

Nina Morrison of the Innocence Project noted that virtually all of them—24 of the 25 cases—were either Black or Latino.

These men served “an average of over 17 years in prison; the one white exoneree, a victim of a politically motivated election fraud prosecution, served no prison time.”

She notes, “The report also finds that the evidence police gathered against many of these exonerees was clearly flawed from the outset — raising obvious questions about why so many Brooklyn citizens of color were prosecuted at all, and why none of the system’s actors stepped in to halt these prosecutions or rectify them for decades.”

While George Floyd’s death and other officer-involved killings draw our attention, police misconduct does not only consist of excessive force or officer-involved killings—it is also one of the leading causes of wrongful convictions. It punctuates other problems: prosecutorial misconduct, Brady violations—the withholding or destruction of evidence, false confessions, and even eyewitness identification problems.

As Vanessa Potkin of the Innocence Project points out: “Though research on the role race plays in wrongful convictions has been limited, existing studies show that Black people are seven times more likely than white people to be wrongfully convicted of murder, and that Black exonerees spend an average of 10.7 years in prison before they are released, compared to 7.4 years for white exonerees.

“The reality is, eyewitness misidentification and police misconduct often lead to wrongful convictions, but it’s important to discuss the racial inequalities that exist when either of these things occur.”

Pervis Payne has spent the last 32 years on death row. The Innocence Project believes that DNA testing could prove him innocent.

He has maintained his innocence for more than 30 years. Yet, despite having no prior criminal record and living with an intellectual disability, he is set to be executed in Tennessee on Dec. 3, 2020.

But evidence exists that could set him free. Last December, Payne’s attorneys found hidden evidence that has never been tested for DNA.

Last week, the Innocence Project joined Kelley Henry’s team at the Federal Public Defender’s Office in Nashville and the Milbank firm in filing a legal petition for DNA testing of newly discovered evidence in Payne’s case that could help prove his innocence.

Vanessa Potkin said, “The rush to judgment and presumption of guilt is prevalent in cases where the accused is Black. These racial disparities have serious consequences, especially in capital punishment cases.”

In the case of Pervis Payne, there are of course serious concerns about whether he’s actually guilty.

She writes: “Prosecutors relied on heinous racial stereotypes to concoct a false narrative about Pervis, ultimately ending with a jury convicting him and sentencing him to death. And crucial evidence from the crime scene (which was withheld from the defense team) has never been tested for DNA.”

Potkin adds, “Pervis, like 42% of defendants on death row, is Black — and like many studies have shown, because the victim was white and because he is Black, his odds of being sentenced to death were much higher.”

Join us in two weeks for the Vanguard’s 10th annual fundraiser – http://vanguard-godsey.eventbrite.com

—David M. Greenwald reporting

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9