By Julietta Bisharyan and Nick Gardner

Incarcerated Narratives

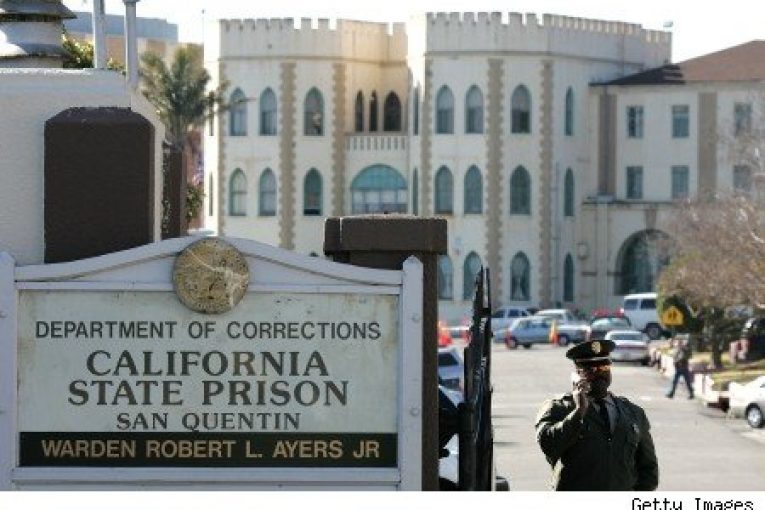

Incarcerated writer Rashaan Thomas recently shared an excerpt with Business Insider discussing the state of COVID-19 inside San Quentin State Prison. Thomas, a 2020 Pulitzer Prize finalist for his podcast “Ear Hustle”, is currently serving a 55-years-to-life sentence for murder. 19 years into his sentence, Thomas details how he has effectively been given another punishment— one that could possibly claim his life and the lives of fellow incarcerated people at San Quentin.

“I’m seeing COVID-19 knock us all down in a line, just like dominoes.”

According to Thomas, San Quentin has all but assured that everyone within its walls will contract the deadly respiratory virus.

“Everyone mingles in one space, one after the other,” Thomas wrote.

For many incarcerated, the only indication of a positive test is for a corrections officer to “key your door.” Once keyed, they are no longer permitted to dine with the larger population and instead designated to a group of other positive cases. Between the arrival of the non-infected population and the infected population in the dining area, nothing— including railings and tables— are cleaned.

Thomas lives in San Quentin’s North Block, where the virus is spreading at the fastest rate within California’s largest prison. The North Block is almost exclusively comprised of people convicted of violent crimes, and as of now impromptu COVID-19 legislation is not allowing for these people to be released. In the eyes of Thomas, the virus will have soon spread to every member of the North Block, and ultimately “it’s up to the disease whether we live or die.”

To Thomas, this legislation fails to recognize that many of these offenders have not committed a crime in 20 years, and are no longer violent people.

“Is that justice? Should I die of COVID-19 because of what I did, when the prosecutor didn’t even seek the death penalty? The message I’m getting is that you would rather see us dead than let us go free.”

A positive COVID-19 test will likely accompany a slew of undesirable side effects— such as headaches, coughing, and shortness of breath. However, for Thomas, the worst part is the anxiety it instills within San Quentin’s population.

On July 3, Thomas discovered that he had tested positive for COVID-19. Thomas’ most noticeable symptom was a “pounding” headache, and most other positive cases within San Quentin describe relatively mild conditions. But there are exceptions, and in such close living quarters, these exceptions can seem like an eerily possible reality.

One of these exceptions was Thomas’ neighbor Ron. Ron recently left the North Block with a fever after testing positive, and is now hooked up to a respirator at an outside hospital. Recently, Thomas saw a man on the tier below him being carried out on a stretcher because he could not breath. Thomas wondered whether or not his nasal passage would eventually close.

Thomas believes that he will survive without a trip to the intensive care unit, but others with high-risk medical conditions may not be so fortunate. 21 people in San Quentin have already died. Thomas personally knows 5 North Block residents who have served over 40 years and are close to being released.

Will they live to see the day, he wonders?

According to Thomas, there are people within San Quentin who are not ready to be released. Some of these people may never be ready. However, Thomas firmly believes that out of 3200, 900 people could be released without threat to the public. Some of them, he believes, would actually improve society.

But many people would likely remain reluctant to support the release of Thomas and others with similar violent convictions. However, after 20 years behind bars, Thomas disagrees.

“Most people age out of crime at age 40. Hell, a lot of these ‘menaces to society’ here are grey-haired old men on walkers and canes. We’re the safest group to release…”

In closing, Thomas wanted readers to know that COVID-19’s presence in San Quentin is not the result of a natural disaster, but rather the direct consequence of a flawed system.

“In prison, you can’t get the virus unless someone brings it in. In our case, they transferred the virus here from another prison. They didn’t learn and transferred it from here to another prison— instead of letting people go.”

And now that the deadly virus continues to spread through San Quentin in the absence of a coherent strategy, Thomas has a different look on his punishment: 55 years-to-life plus COVID-19.

“As horrible as I was years ago, I killed one person. Now 22 people have died in my prison alone from the COVID-19 fiasco.”

A man recently released from San Quentin died in a Novato hotel on Aug. 15, and his family are demanding answers from prison officials.

Mike Madeux, a diabetic, was granted an early release from San Quentin after contracting coronavirus in late July. Madeux was ordered to quarantine at a hotel in Novato where he was allegedly given very little state support, at times going days without food.

Shortly after arriving in Novato, Madeux agreed to interview with KPIX 5, where it was first discovered that the state had taken days to deliver his first meal.

Roughly a week after his first interview, Madeux’s family became concerned after he stopped returning their phone calls, and 2 days before Madeux’s quarantine was scheduled to end, his mother received a phone call informing her of her son’s passing.

During the 12 days spanning his release from San Quentin and his tragic passing, both Madeux and his family members had raised concerns over the treatment he was receiving.

In his interview with KPIX 5, Madeux described begging CDCR for help with managing his diabetes.

“I’m diabetic,” Madeux told officials. “I am shaking because I haven’t had anything to eat and they hand me no meter to check my blood sugar levels.”

On the conditions of his release and ensuing state-sanctioned quarantine, Madeux was supposed to receive help meeting food and transportation needs. However, this was never the case.

His mother, Teri Sue Maduex, was concerned with the fact that her son was left alone in a hotel, rather an emergency room, which she had recommended in her last phone call to him.

Madeux’s family is now questioning the actions taken by the CDCR leading up to Madeux’s death.

“I want something to happen,” Teri Sue Madeux told KPIX 5. “I don’t think they treated him right. I don’t think they should get by with what happened.”

CDCR Confirmed COVID-19 Cases and Outcomes

As of Aug. 21, there are a total of 9,789 confirmed COVID-19 cases in the CDCR system, with 1,027 in the last two weeks. 12.6% of the cases are active in custody while 3.4% have been released. 83% of the cases have been resolved.

There have been 55 deaths across the CDCR system thus far, two this week.

On Aug. 18, an incarcerated person from Mule Creek State Prison (MCSP) in Ione died at an outside hospital from what appear to be complications related to COVID-19. This is the first COVID-related death at MCSP.

There has also been another death at CA Institution for Men (CIM) in Chino. There are now 20 deaths there, constituting 37% of the total death count.

In addition, San Bernardino County officials notified San Quentin State Prison this week that Dean E. Dunlap, 61, had died at an outside hospital back on Jul. 29.

Dunlap was sentenced to death in San Bernardino County on April 14, 2006, for first-degree murder and was admitted onto California’s death row ten days later. He had previously been convicted of raping, kidnapping and killing a 9-year-old girl in 1992.

The San Bernardino County Coroner’s Department is still yet to determine Dunlap’s cause of death.

MCSP has resolved 25 active cases this week –– 23 in one night. Meanwhile, CA Correctional Institution (CCI) in Tehachapi has resolved 62 active cases this week.

Since Aug. 20, there has been one active case of COVID-19 among youth at the Division of Juvenile Justice facilities. 67 cases have been resolved.

At Folsom State Prison (FSP), cases have more than doubled in the past week, now representing the largest current outbreak among the state’s prisons. FSP currently has 235 positive cases.

Just last week, the prison reported 99 incarcerated people with active cases, plus another seven who were either inactive or were released. On Aug. 11, CDCR announced that it was setting up tents as “proactive isolation/quarantine housing” options for patients to be screened by health care staff directly. CCHCS also sent a nursing/health care strike team to assist.

As of Tuesday, a large tent with a 90-bed capacity has become available for COVID-19 patients at FSP. According to CDCR, more than 1,000 incarcerated people have been tested since Aug. 12 with less than 1% of results coming back positive.

There has been an 81% increase in CDCR cases since Aug. 9. San Quentin still holds the most cases –– 2,236.

COVID-19 in CDCR’s San Quentin

In the case against San Quentin State Prison (SQ) and CDCR for the mismanaged transfer and handling of the resulting COVID-19 outbreak, lawyers for 42 incarcerated people in San Quentin are suing for immediate release, citing “immeasurable suffering inside and out.”

On Aug. 12, Marin County Superior Court Judge Geoffrey Howard, who is overseeing the case, issued an order allowing a second consolidated case involving 115 more petitioners to move forward.

The filing revealed that San Quentin ignored the advice of Marin County Public Health Officer Matthew Willis and that CDCR issued letters to local health officials claiming that state prisons are exempt from local health orders.

The cases were filed individually as “habeas corpus” petitions –– an emergency motion asking the courts to determine whether a person’s incarceration is lawful. As more individuals continue to file petitions, more plaintiffs will get added to the case.

Last month, Judge Howard issued the first order in the current consolidated cases of 157 petitioners. The court ordered the state to respond urgently to the petitioners’ requests for immediate release from San Quentin.

The petitioners allege that their 8th Amendment right to be free from “cruel and unusual punishment” has been violated, making their incarceration unlawful. In addition to early release, there is a demand for a 50% reduction of the prison population.

According to San Francisco Public Defender and State Policy Director Danica Rodarmel, the only remedy is release.

“This whole problem has been caused by mass incarceration, overcrowding in our prison systems and overcrowding in San Quentin. We have public health experts saying that it needs to be reduced by 50%. That didn’t happen.”

Rodarmel believes that a 50% population reduction is more than reasonable, citing that 50% of the prison population in California has been deemed to be low risk by CDCR’s risk assessment tool.

Petitioner Arthur Jackson’s wife, Veronica Jackson, said, “I told my husband on the day we got married that I wouldn’t excuse the man he was, but that I will embrace the man he is now. That is what we are asking the people in power to do –– to please treat him according to who he is today, and allow him to come home.”

Particularly in San Quentin, where most individuals are transferred to after they’ve been incarcerated for a long period of time and have had access to many programs, it is likely that half of SQ’s population can be released safely, says Rodarmel.

“The complicated part is that the state’s made it clear that they’re not interested in releasing those who have life sentences. That’s a big part of the population at SQ,” Rodarmel added. “But that also means they’ve been at prison for a long time and have clearly aged out of crime. They are refusing to let out exactly the people they should be letting out.”

Instead of spending over $80,000 a year to incarcerate an individual in CDCR, Rodarmel believes that the money should be redirected into reentry programs and to help house those who are recently released.

The filed petitions, which has over 400 pages detailing failures by CDCR and SQ, came after CDCR transferred 121 people from the California Institution for Men (CIM) in Chino, then the state prison with the highest COVID-19 rate in California, to San Quentin in late May. As a result of the transfer, over 2,000 people incarcerated and working at San Quentin have tested positive for COVID-19 and 26 have died.

Currently, the COVID-19 infection rate in San Quentin is 68.5% while California’s infection rate is 1%.

According to Rodarmel, who just sat through the first case management conference, the judge has been signaling that he’s going to order an evidentiary hearing, which will give the legal team an opportunity to make their case against CDCR.

Both the judge and the Court of Appeals have expressed that there have been serious failures done by the state in regard to CDCR’s handling of the pandemic.

“I don’t believe we live in a society where this kind of power and harm should go unchecked. I’m hopeful that the judges hearing these cases will also feel that way and see that. As a legal matter, I think it’s very clear that there’s been an 8th amendment violation here,” said Rodarmel.

CDCR Staff

Amid the growing outbreak, one Folsom State Prison (FSP) employee had died due to complications from COVID-19. The employee was a five-year veteran of the facility.

The number of Folsom State Prison employees who have contracted COVID-19 has nearly doubled in one week, currently at 15 cases. According to CDCR, five of those employees have since recovered and returned to work.

There are currently 2,518 staff cases in CDCR facilities. 1,261 are currently active while 1,257 have returned back to work.

San Quentin makes up 11% of the total staff cases.

Effect of CDCR Outbreaks on the Public

Protestors gathered last Thursday evening outside of California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Secretary Ralph Diaz’s home to host a candlelight vigil in recognition of the 53rd COVID-19 Death at San Quentin State Prison.

According to protesters, Diaz failed to keep incarcerated people safe by denying cleaning supplies to those within the prison.

In attendance was Belinda Morales, whose husband recently passed from COVID-19 while in custody in Chino’s California institution for Men.

“I just want there to be change, people to be held accountable, it won’t bring him back but he’s got a brother in there. He said it’s impossible — impossible — to social distance,” Morales told the Sac Bee.

Coronavirus in California prisons remains a daunting issue, with over 9,000 confirmed cases of the virus at the time of the protests. Steps are being taken to limit the spread, such as non-violent prisoners being released conditionally, however many are still upset at the treatment of those still inside during such a stressful and unpredictable time.

Joanne Scheer, whose son is incarcerated, finds the lack of communication between prisons and family members of incarcerated people disturbing— leaving many to wonder whether or not their loved ones have contracted the deadly respiratory disease.

“Loved ones of those incarcerated are not informed when they contract COVID-19. If our loved one is sick, family members are disallowed the compassion and consideration of a simple phone call. We are informed only when our loved one has died.”

Protesters are calling on Diaz to release all at-risk people from custody, namely elderly and immunocompromised people. They are also calling for a suspension of transfers between jails and prisons, which includes transfers to Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody.

Another devastating California wildfire season has arrived, and amid a nationwide pandemic that has claimed millions of jobs, many of the state’s residents will now turn to Cal Fire to protect their home, property and livelihood.

But each year, a group of unsung heroes step in to provide 3 million hours of emergency response work and 7 million hours in community service. They will save California 100 million dollars in taxpayer money, as they do most years. They will be paid, at most, 5.12 cents per day risking their lives for the public. These are California’s incarcerated firefighters.

One such firefighter is Edward Lopez, who spent the last 10 months of a nine-and-a-half-year sentence fighting fires while incarcerated at the Eel River Conservation Camp in Humboldt County. Last year, Lopez was deployed to nearly every fire in Northern California.

However, in the wake of COVID-19, transfers into Conservation Camps— where many of these incarcerated firefighters are housed— has been limited.

As Lopez pointed out, the role of these incarcerated people extends far beyond fighting fires. Between fires, Lopez builds bridges, clears brush and downed trees, works in state parks, and offers support to Caltrans.

“A lot of these small communities throughout the state cannot be functional without incarcerated firefighters because you have roads and bridges and we are the ones who do all the work to them to prevent fires,” Lopez told SF Bayview. “Without us, it would be a slow process. We are helping communities.”

42 Conservation Camps exist in 27 counties throughout California and are home to 3,367 incarcerated people, 2,089 of which are firefighters. To become an incarcerated firefighter, one must satisfy the security risk level necessary to qualify, and must have a good track record of behavior while in prison, have 5 years or less left on their sentence, and have been convicted of a crime that is not rape or arson escape. Prospective firefighters must then pass a two-week physical fitness program and a six-to-seven week wildfire training by Cal Fire instructors.

Once these requirements are met, they are assigned a crew.

However, recent legislation has impacted the ability of Conservation Camps to recruit new firefighters.

AB109, which recently passed the California State Assembly, has brought forth changes in sentencing and the realignment of incarcerated individuals, reducing the number of those meeting all the requirements to become an incarcerated firefighter. Additionally, Prop 47 and 57 have proved controversial, along with the Inmate Housing Score guidelines, which also determines whether an individual will be eligible for the fire program.

Eel River Conservation Camp, where Lopez is based, currently houses 77 incarcerated people, down from its former capacity of 132. High Rock Conservation Camp has also seen a reduction in size, only housing 68 of its original 110 person capacity.

As Lopez pointed out, these institutions, which used to be able to operate five fire crews, now only have room for four. This has placed additional strain on the existing units, which are now only allowed a 2 hour break between fires.

“They overwork us and we feel like we get worked hard because our assignment needs to be done in a certain amount of time,” said Lopez. “We have to work with half the people. But at that moment houses [and lives] are in danger.

All this for a mere five dollars and twelve cents per day.

And after these incarcerated people complete their sentences while simultaneously risking their lives for the public, standing California legislation all but bars them from employment in municipal fire agencies.

The majority of fire departments require Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) certification, which convicted felons are restricted from obtaining. These restrictions can be waived, but rarely are.

Through activism, the Anti-Recidivism Coalition (ARC), a nonprofit organization that aims to prevent formerly incarcerated people from reoffending, has pressured the CDCR into revisiting this issue. The result: a program uniquely tailored to former incarcerated firefighters that serves to bridge careers behind bars with careers at Cal Fire. The program, known as the Ventura Training Center, is now home to Lopez, who was accepted last June.

On his first day at the VTC, Lopez and colleagues were visited by two San Diego fire captains. Similarly to Lopez, one captain had served 16 years at Eel River Conservation Camp, before enjoying a 20 year and counting career fighting fires. Lopez described this a “turning point” for his own career.

At the end of the captain’s presentation, Lopez recalls receiving some valuable advice:

“He told me to study and keep my books clean and to call him when I was done.”

As COVID-19 was beginning to accelerate across the United States, experts warned of the consequences of an outbreak within prison systems. The overcrowded, outdated and unsanitary facilities that house America’s incarcerated population meet all the requirements for a swift, uncontrollable spread of the virus. Despite these warnings, when the first cases of COVID finally breached prison walls, institutions across the country were grossly unprepared and lacked an efficient plan to protect their populations.

California, which has historically led the country in progressive policy, was no different.

Recently, a watchdog agency that oversees California prisons released a report assessing the California Department of Corrections (CDCR) handling of the coronavirus outbreak.

Specifically, the report focused on how California prisons are conducting both staff and visitor screening. The report concluded that the CDCR failed to establish clear screening guidelines for these groups, describing standing policy as “vague.” These vague guidelines led to systemwide inconsistencies that allowed both staff and visitors to facilitate the virus’ spread between the public and the incarcerated population.

In fact, during some of the watchdog’s visits to these institutions, agency staff were not screened for known symptoms of coronavirus.

These grievances are consistent with a similar assessment by the Prison Law Office, who has filed suit against the CDCR over substandard prison conditions and the absence of comprehensive testing that prevents staff from introducing the virus to incarcerated people.

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) will also conduct three separate reports looking at the availability of protective gear and treatment of prisoners with COVID-19.

As of August 17, 9,500 incarcerated people in California had tested positive for COVID-19. Additionally, 2,000 CDCR staff had tested positive. Of these cases, 54 incarcerated people and 9 staff have passed away.

OIG inspectors discovered that CDCR staff were untrained and under-equipped to successfully fight COVID-19 within prisons. Some staff had even been given faulty thermometers that lacked a working battery.

The report is recommending that the CDCR introduces strict procedure ensuring that all prison entries are screened. It is also recommending that thermometers are constantly tested and that extra batteries are kept on hand.

The OIG also alleged that the CDCR had withheld information that limited their analysis for parts of the report— a misdemeanor under California law. The Secretary of the CDCR has since decided to release the information.

A union representing nurses from Curry County, California, have recently filed a grievance against the state for violating their employment contract by requiring nurses to work at Pelican Bay State Prison. Within the contract is a clause protecting nurses from working environments where a clear and present threat exists to their health and safety. As of August 17, 26 staff at Pelican Bay had tested positive for COVID-19.

Upon arriving at work early last week, nurses were met by members of Local 1000 of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) who were handing out fliers notifying staff of a recent vote of no confidence in CEO Bill Woods and his medical management team.

Among concerns raised by union representatives was the disparity of testing between incarcerated people and staff. Whereas inmates would receive test results quickly, the turnaround for staff was alarmingly slow.

Testing issues played a role in the former executive’s ousting, but union reps ultimately credited the vote of no confidence in Woods to a “toxic work environment” that was cultivated during his tenure as CEO.

“It’s been going on for years, and it’s gotten worse with the promotion of Bill Woods,” said Jerome Washington, president of the District Labor Council 749. “It’s been a pattern with management trying to get compliance with employees using threatening behavior.”

According to Laura Slavec, a district bargaining representative for the SEIU and dental assistant of 8 years at Pelican Bay, Woods led by fear and intimidation— a dynamic similar to that of “an abusive relationship.”

Woods, who served the position for seven years, is yet to comment on the vote.

As for the claims of disparity between COVID-19 tests for incarcerated people and staff, Kyle Buis of the California Correctional Health Care Service believes this to be a result of separate testing processes for the two groups. Testing for the incarcerated population is done within the prison, whereas staff are tested through privately contracted companies.

“Due to the amount of tests, while accompanying high demand both statewide and nationally, some vendors in certain areas have experienced delays with test results,” Buis noted. Naturally, tests done within the prison will avoid such obstacles.

Other experts have pointed out the danger of staff interacting with the incarcerated population. Dr. Warren Rehwalt, public health officer for Del Norte County, raised concern over this issue at a recent county Board of Supervisors meeting:

“The big issue with COVID-19 and testing here is that the people who work in this institution live out in the community,” said Washington. “So if you have an outbreak in a highly-populated area like Pelican Bay, it’s going to quickly spread to Crescent City and Del Norte County. The medical system wouldn’t be able to handle a big increase of positive cases here.”

Rehwalt, however, is optimistic in CDCR’s ability to mitigate this threat.

CDCR Comparisons – California and the US

According to the Marshall Project, California prisons rank fourth in the country for the highest number of confirmed cases, following Texas, Florida and Federal prisons. California makes up 9.4% of total cases among incarcerated people and 6% of the total deaths in prison.

There have been at least 2,385 cases of coronavirus reported among prison staff. 9 staff members have died while 1,100 have recovered.