By Beth Miller and Peter Eibert

In this episode of the Vox Podcast Conversations, host Jamil Smith interviewed progressive prosecutor Larry Krasner. Together, they explored the answers to the questions “is it possible to work within the system to change the system?” and “how much can one person do?”

Who is Larry Krasner?

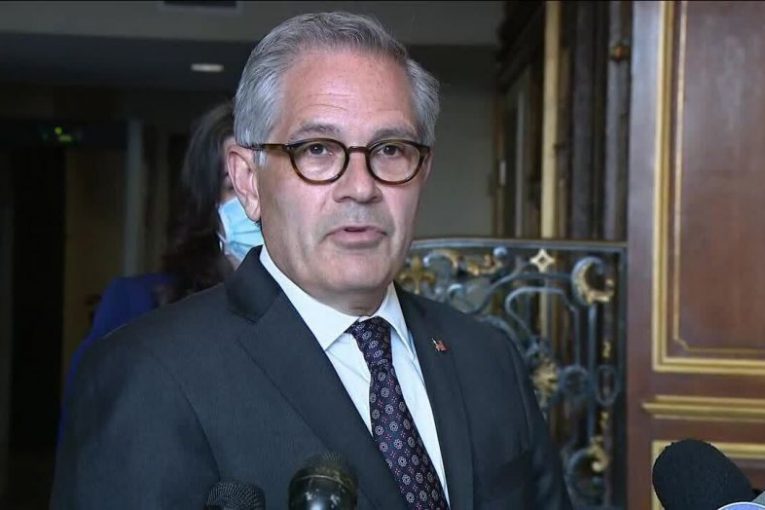

Krasner is one of the most famous progressive prosecutors recently elected. In 2017, Krasner was elected as the 26th District Attorney (DA) of Philadelphia.

Formerly, Krasner was a civil rights attorney who diligently fought for civil rights: he even sued the Philadelphia Police Department 75 times during his 31 year career.

As DA, Krasner maintains a rhetoric that law enforcement is “systemically racist” and has devoted his career to trying to change the system from within.

To fix the system, he intends to populate his office with data scientists and criminologists, end cash bail, induce reform to the probation system, and reduce rates of incarceration, particularly among juveniles.

What does a DA do?

DAs are the chief local prosecutors at the county or state level. The responsibilities of a DA include deciding who to charge, what to charge them with, and what the appropriate response for each case is. For example, the DA can request conviction or a more rehabilitative approach.

Krasner notes that the everyday actions and decisions of DAs have a significant impact on the rate of incarceration and whether money is invested in prevention or incarceration.

How has your victory resonated with the city and with Krasner?

Krasner received 66.7 percent of the votes in the democratic primary for Philadelphia DA this past year, while his opponent Carlos Vega received just 33 percent of the vote.

The election was of paramount importance, as he said that it was “the last stand of progressive prosecutors” in the face of vocal backlash to progressive prosecutors due to a purported increase in gun violence over the past year.

Krasner’s overwhelming victory validated the existence of a grassroots movement for criminal justice reform. “This shows…that the people are way ahead of their elected officials and their institutions and they want real criminal justice reform.”

Culture of fear and blaming progressives

Krasner mentioned a recent marked increase in the use of fear in politics. He rebuked the use of fear in politics, and then stated that “it’s [fear in politics] worst enemy is a rational and scientific approach to criminal justice,” an approach which Krasner proudly uses.

Krasner lamented how the mainstream media tends to favor reporting individual cases which are uniquely terrible while brushing the systematic issues of the justice system and declining crime rates under the rug.

For example, gun violence rates increased substantially in the past year. Former President Trump highlighted this fact in his reelection campaign to promote a view that America was falling into lawlessness to promote himself as the candidate who would restore law and order.

However, the overall crime rate declined: the country had not fallen into abject lawlessness. Rather, America had specifically suffered from a surge of gun violence, not crime in general.

Krasner criticized the double standard of how the public judges progressive prosecutors. He firmly believes that progressive prosecutors are unfairly blamed when crime goes up, but that traditional prosecutors who promote longer and harsher sentences do not face similar criticism when crime rates increase under their watch.

Incarceration in Philly – two steps forward, one step back

When Krasner took office in 2018, the number of people in county custody was approximately 6,500. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Krasner brought that number down to less than 4,000 – the lowest incarceration rate in Philadelphia since 1985.

Unfortunately, the pandemic’s shutdown of the courts halted, and even reversed, Krasner’s progress. The result was that cases were not being disposed of, even while arrests continued, many of which were for gun violence.

Even Krasner’s best efforts to retain the progress he made were not enough. He stated that “even though we were trying to do with the public defenders what we could, the inability to try cases, the pressure to resolve cases, [and] even the correctional systems’ refusal to move inmates from the country system [all contributed to the increased incarceration rate].”

No cash bail

During the pandemic, Krasner shifted his focus to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in prisons and the general population. His solution was to introduce no-cash bail.

No-cash bail also had the added benefit of reducing the amount of poor people in jail for minor offenses. It also ensured that dangerous criminals could not get out on bail easily, even if they were very wealthy.

Indeed, Krasner believes that “cash bail doesn’t work… It incarcerates poor people for dumb stuff and at the other end it lets out people with resources for really serious [crimes].”

Krasner and his administration’s new no-cash bail system either did not ask for any cash, or it asked for $999,999. If they asked for $1 million or more, Pennsylvania law would have required that the cash be handled in a non-socially distanced manner.

Krasner and his administration think that their no-cash bail system was a success. He hopes that the Pennsylvania legislature will change the state’s cash bail system in the future.

Solutions for gun violence

The geomap of violent crime, i.e. a map of where violent crime occurs, is identical to the geomaps for poverty, unemployment, mass incarceration, and low educational achievement. Most often, Black and brown communities are harmed the most by such issues.

Thus, Krasner believes that the “biggest solutions [for gun crime] are preventative.” Overall, he contends that law enforcement should invest more in prevention than in punishment.

Through investing in prevention, he hopes to cut the incarceration rate by 50 percent in future years, pointing to the debilitating effects that a conviction can have on a person’s life. Krasner said that “the consequences of conviction are so stark in terms of disabling someone from participating in the economy… being a provider, owning a home, obtaining housing, and so on.”

How to sell working within the system to change it

One of the biggest issues that Krasner faces is how to convince black and brown people to trust prosecutors and police with working within the broken system to change it.

Krasner believes that convincing skeptical populations to trust him, his office, and like-minded police will take a lot of effort. The most important step is to get innocent people out of jail. Recently, Krasner started a conviction integrity unit that released 20 people from prison who were wrongfully – and often egregiously wrongfully – convicted.

In post-George Floyd America, the public also expects contracts between police, prosecutors, and public officials to reflect contemporary safety values. Krasner claimed that failure to improve contracts will likely result in the exasperated but passionate public voting out stubborn officials.

Krasner on mandatory minimum sentences

Krasner views mandatory minimum sentences as unjust.

To combat unjust mandatory minimum sentences, he does not pursue mandatory minimum sentences in instances where it’s unnecessary. He also can decide whether to pursue a particular charge at all based on whether the sentencing guidelines are appropriate or not.

He also believes in individual justice: judges, who know the individual facts of a case better than the rigid mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines, should be given more discretion.

Ultimately, he hopes to have unjust sentencing guidelines and other unjust laws taken off the books.

Krasner on the future

Krasner is optimistic about the future of criminal justice reform.

He responded to the critique of progressive prosecutors as being “radical.” On the contrary, he suggested that the newfound massive increase in incarceration since the 1970s based on the war on drugs and animosity toward anti-war protestors and minorities was radical.

Indeed, Krasner emphatically held that “the real radicals here are the ones who are so smitten that nobody should be able to be on the sidewalk and everybody should be in a jail cell.”

The future of criminal justice reform indeed looks bright, according to Krasner. He believes that normal people and grassroots movements are the key to reforming the broken criminal justice system – not the mainstream politicians who claim otherwise.