An Introduction to CSP-Sac

August 3, 2024 was my final day on ‘B’ Facility at California State Prison, Sacramento (CSP-Sac). I only spent thirteen months there, ultimately leaving in a flurry of intrigue and public scrutiny, but in that time CSP-Sac proved itself to be a front-line battlefield in the current war to reform the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). More than merely a notoriously disruptive and violent institution, Sac is unique because of a strange project that began there a few months before I arrived, a project that brings into daily conflict two contradictory correctional philosophies. Collisions like these always have much to teach, truths written in the tragic fallout from lives lived and lost, teetering off the edge, headstrong in their convictions. Abolitionist’s Notebook is a series of articles dedicated to clarifying the nature of those pitted conflicts, attempting, through careful account and critical consideration, to unveil the mechanisms of harm upon which prison is based.

The CDCR is drastically adjusting its strategic mission, attempting to realize a herculean shift away from a strictly security-based objective. It is sluggishly pivoting towards the California Model, aspirations which are altogether foreign to the carceral sphere. The problem posed by this shift, beyond new tactics and training, beyond updated technology and architecture, at its core, is a problem of culture, and prison administrators throughout the state are all faced with a plaguing question: How do you address the sheer toxicity of correctional beliefs, values, and modes of communication, the violent and self-traumatizing ideologies which have formed amidst the unchecked harm and brutality of the last forty years? CSP-Sac is a stronghold of that past, a venerable relic of the worst CDCR has to offer, and for that reason, the cultural shift attempted there is particularly interesting.

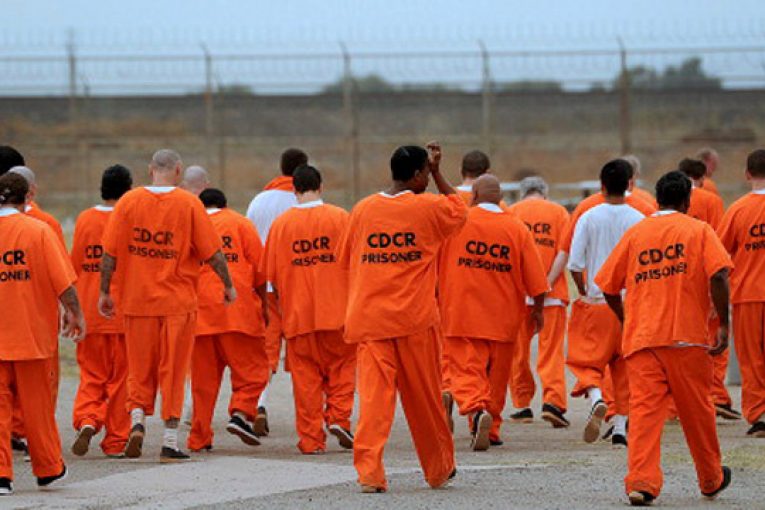

CSP-Sac is a super max, high-security institution, designed to lockdown and chain up every conceivable vestige of captive humanity. The landscape is peppered with tiny holding cages, built to contain a standing human body; security checkpoints enclosed by fences and razor wire, erected on the idea that a mob of ravenous insurrectionists could storm it at any moment; countless concrete encampments, each intended to segment and segregate the incarcerated into smaller and smaller groups, to limit and contain the greatest danger of all: free assembly. Walking the yard, you can see that the walls are littered with pockmarks, craters from bullets shot into combative crowds; orange spray paint is everywhere, marking the pieces of metal which have been carved from desks and lockers and doorframes, steel forged into weapons and wielded by those forced to live out their days here, craven conductors orchestrating their own tragic and frequent folly. Is it fair, though, to say that the incarcerated are the makers of their own brutal discord?

At CSP-Sac, murder is common, accidental or incidental deaths are routine, and bloody conflict (fights, stabbings, staff assaults, riots) are so frequent that they are discussed as casually as the weather. More than mere commonality, a high value is placed on the violence that plays out here, and for that, such violence is celebrated. It is cultivated, and it is depended upon by custody; violence is the chief commodity within CSP-Sac’s terrible economy of labor.

This place needs violence, it thrives on it, but why wouldn’t it? There is no money in harm prevention. When responding to the life problems faced by the incarcerated, there is ever mounting evidence that care is a more effective pursuit, as it is less costly and it strengthens community; however, although harm destroys community and is grossly ineffective at responding to life problems, in prison, it is the default practice relied upon by correctional personnel. This reality reflects the economy of harm, characterized by ineffective responses, hazard pay and the countless hours of overtime dedicated to investigation and report writing, to use of force training and mandatory gun coverage. Violence means work hours. It means economic security, and whether intentional or implicit, the production of violence at CSP-Sac is hardwired into custodial culture.

In May of 2023, ‘B’ Facility at CSP-Sac became, in part, a level II Non-Designated Programming Facility (NDPF)¹; however, ‘B’ Facility also maintained its level IV Enhanced Out-Patient (EOP)² designation, creating what administrators at CSP-Sac refer to as a “bifurcated” program. Both of these populations share the same yard but are segregated to their own housing units and, for the most part, program separately. Where bifurcation, perhaps, has occurred, this is certainly the most drastic delineation drawn between two groups who, as far as program security concerns go, couldn’t be more starkly divided.

The principal challenge that bifurcation poses, at least at CSP-Sac, is one of custodial culture, bringing medium-security incarcerated folx in contact with correctional personnel entrenched in high-security modes of interpersonal communication and custodial interaction. This means officers who brood with mistrust, open hostility, and outspoken disdain for the incarcerated, subjecting level II’s to confrontational and aggressive modes of communication and procedural engagement typically afforded to level IV’s. For many level II’s, this type of custodial interaction has never been experienced or (for those who have worked years to descend in security levels) represents an environmental adversity the department assured them they would no longer be exposed to; however, as this series of articles will attempt to demonstrate, CSP-Sac is an uncompromising land of broken promises.

In addition to a bubbling cauldron of cross-cultural conflict, bifurcation also brings with it innumerable operational complications, as two segregated populations are forced to share a facility that already has limited space and programming opportunities. Challenges have arisen across the board, plaguing the distribution of carceral resources in every category. At CSP-Sac, employment, education, and rehabilitative programming have all proven to be mires of dysfunction, administrative incompetence, custodial interference, and incarcerated corruption, leaving those level II individuals unfortunate enough to be sent there withering on the vine. The inevitable result from such beleaguered opportunities can be read in the troubling and disproportionate frequencies of community issues that have taken root in the first year of the bifurcated program.

In March of 2024, a drug epidemic swept the facility, resulting in countless overdoses and one confirmed death; however, on the inside, and beneath the sight of institutional reporting, I watched as people with years of clean time relapse, one after another, succumbing to boredom, the impossibility of gaining employment or continuing their education, and endless waitlists for a minimal number of groups which, as every new cohort began, the brazenness of favoritism and line-cutting left those on the outside feeling forgotten and without hope. No jobs meant an uptick in illicit ventures: no school, no groups, and no in-cell arts program left many adrift and without purpose, vulnerable to the temptation of getting high or drunk, partaking in substances that widespread unemployment had made readily available. Overall, these conditions deteriorated the possibility of building a rehabilitative community and provided the necessary means to construct the opposite. Ill contempt and bitterness flourished, tempers and self-sabotage flared, and people rolled up, one after another.

One of the standout challenges at CSP-Sac is the desolate state of rehabilitative programming. In one sense, numerous problems are created because of space limitations; however, it is also challenging to convince community members to volunteer their time to visit an institution with such a notorious record of violence and instability. Given these limitations, the few existing groups and activities are scarce, thus creating heated competition within the incarcerated community, a competition waged not merely in participation, but also amongst those attempting to facilitate groups. Here the challenges of bifurcation, as well as the overall mismanagement and maldistribution of community resources, paved the way for a highly centralized and thoroughly corrupt rehabilitative oligarchy to form–though oligarchy conveys an elite expertise to which this group certainly should not be attributed.

These lack of opportunities, combined with administrators’ indulging in the reckless empowerment of questionable characters, set the stage for an unchecked exploitation of communal vulnerability, allowing self-serving carpetbaggers to gain a stranglehold on ‘B’ Facility’s programming opportunities. These wretches took full advantage of the bleak situation, positioning themselves as makeshift rehabilitative tsars, attempting to screen out others from starting groups, asserting corrupt and unaccountable influence on participant selection, appointing subordinate facilitators of indebted tutelages, and politically sabotaging all who opposed their communal abuses. In a strange iteration of official corruption, however, the abuses of this rehabilitative oligarchy became hybridized with the incarcerated community’s representative body, constructing a powerhouse of administrative influence and unchecked control over the programming resources provided to the incarcerated on ‘B’ Facility.

The primary means by which incarcerated communities in the CDCR are afforded agency, the ability to formally raise concerns about conditions on their facility, is through the Incarcerated Advisory Council (IAC). The IAC is a procedurally safeguarded representative body that every incarcerated population in the CDCR is supposed to be afforded. These representative bodies are granted certain organizational rights, including an office and necessary clerical resources (computer, duplication abilities, etc.), the ability to hold meetings with administrators and keep formal minutes, and the ability to confidentially correspond with members of the legislature and the media.

Given that an IAC is the primary source of an incarcerated community’s agency within their institution, it should be unsurprising that, at CSP-Sac, the IAC would prove to be a crucial vector for community theft, corruption, and collusion with custodial attempts to interfere with and discourage the advancement of programming.

In August of 2023, then Sergeant McCoard (who is also a Union Representative Supervisor for Bargaining Unit Six) orchestrated an IAC election many residents claimed to be fraudulent. Multiple sources report that McCoard disqualified eligible candidates and substituted those candidates of her own, and she was seen disposing of official ballots prior to them being counted. The IAC body, which formed from this election, was widely considered by the incarcerated community to be illegitimate, and in the months that followed, it would prove to be so. Officials on this body flagrantly stole community resources, exploited the IAC office and its allotments for personal gain, attempted to gate-keep and screen community participation, circumvented election proceedings to appoint body members, and did all of this while failing to advocate in any meaningful way for the needs of the population. Disgusted by these actions, I joined the body intending to oppose, and hopefully foreshorten these avenues of blatant abuse. I considered my role to be that of a double agent, working within and against a corrupted body, while also trying to wrestle as many resources and opportunities free from the grips of these tyrants as possible, trying to distribute them to my beleaguered community.

Approaching my role as secretary from an abolitionist perspective, I attempted to kick down a number of custodial and administrative doors, which prevented my community from realizing a full level II program. I oriented my work and the fulfillment of my official duty around three central pursuits: 1. the enhancement of community agency, 2. the expansion of programming opportunities, and 3. the improvement of the community members’ quality of life. These pursuits were met with consistent opposition, coming both from custody and self-serving factions of the incarcerated community; in this sense, some frequent barriers and pitfalls impeded my hopeful progress. Approaching these challenges as a journalist, however, and understanding the unique and procedurally safeguarded relationship between the IAC and the media, I kept thorough official notes and record-keeping and disclosed–through confidential correspondence–mountains of internal documents to the VIP. Because of these efforts, I am able to report on my time at CSP-Sac with evidence and accuracy, shedding light on, what by all accounts, is a tightly woven debacle of administrative ineptitude, custodial corruption, flagrant misconduct, and outright villainy from within the incarcerated community.

The various topics mentioned here are all stories unto themselves. It is for this reason that, in the coming months, we will be printing a series of articles which report, in detail, on the events which transpired at CSP-Sac during the year I spent there. This reporting is necessary not merely to expose the abuses that are perpetrated at Sac daily, nor simply to call out the bad actors–in green as well as blue–who are active participants and co-conspirators in such harm, but also to open up a larger discussion on our work as abolitionist journalists living and struggling to survive within a brutal and oppressive institutional landscape. I hope to drive forward a conversation about carceral community building, about purpose and intent, while also presenting my attempts to put theory into action, considering both my successes and failures from a critical perspective.

Through this series, I hope others dedicated to similar pursuits will gain knowledge and inspiration. There is still a war of abolition to be waged from the inside out, and many of us are actively engaged in it. We can learn from one another, fortify our struggle by reading of lessons learned and of battles fought against correctional abuses, which, though having occurred far from where we are, still played out behind prison walls which, ultimately, are all the same. We are often our own worst enemies, and it is only by laying ourselves bare to our comrades, by exposing our failures and shortcomings in truth and humble authenticity, that we can grow as a united force, mending the breaks in our lines and knowing better how to identify and turn out the saboteurs and betrayers that lurk within our ranks. The stories we tell matter, but only if we tell them. Stay tuned for more.

¹NDPF refers to a high-programming, medium security correctional facility design, and which is made up of individuals designated as both general population and protective custody (sex offenders, informants, dropouts, members of the LBTQIA+ community). These facilities are intended to facilitate positive programming through greater trust and familiarity shared between custody and the incarcerated.

²EO refers to the most intensive level of mental health treatment status in the CDCR. These individuals are required to attend structured treatment groups five days a week, and typically represent individuals with severe personality disorders, mental instability; as well as, individuals with demonstrated patterns of psychotic episodes, the habituated propensity for harming themselves and/or others, and other institutionally disruptive behavior. EOP level IV populations are typically some of the most violent and unstable groups within the department, thus being afforded significant staffing and security oversight resources.