(Or at least it’s supposed to.)

Perhaps the greatest casualty of mid-century modernist thinking was the love affair we fell into with the automobile.

Cars became synonymous with freedom, prosperity, and “the American dream,” and they enabled us to escape the cities and sold us a vision of everyone living in their own little private cottage out in the countryside.

The history of this “great suburban experiment” is equal parts fascinating and disappointing, And we are still feeling its effects today in a variety of ways, but the one consequence we want to talk about today is how we forgot how to build for transit.

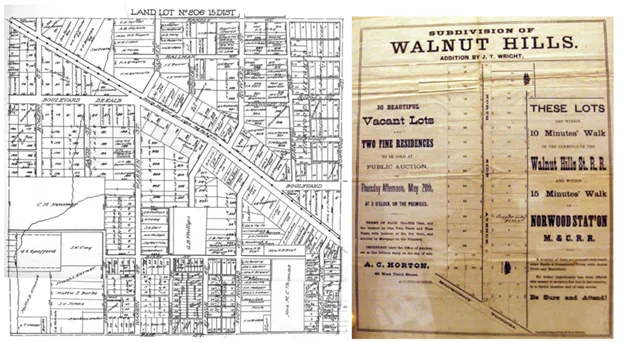

Before the advent of the car, almost every city in the country that had a population above 10,000 people had a streetcar line: a way of moving people faster and more efficiently than walking or carriage. Suburbs were already becoming a thing, but they were “streetcar suburbs”: housing built along the path of a streetcar, trolley or rail line where people could walk from their homes to the transit line, and then take that transit where they needed to go.

The constraint of keeping all of the city’s housing within walking distance of these transit lines forced the cities to remain somewhat compact, and the surrounding countryside fell off into agricultural lands fairly quickly. It also meant that people who were wanting to build housing had first to figure out how to build a transit line to their development, and often, developers did just that.

With the advent of the automobile, however, there was no longer a limit to the city’s horizontal spread, and instead of densifying the neighborhoods around our transit corridors as our population grew, we abandoned the old structures in these older areas, and simply built new housing on undeveloped land on the periphery.

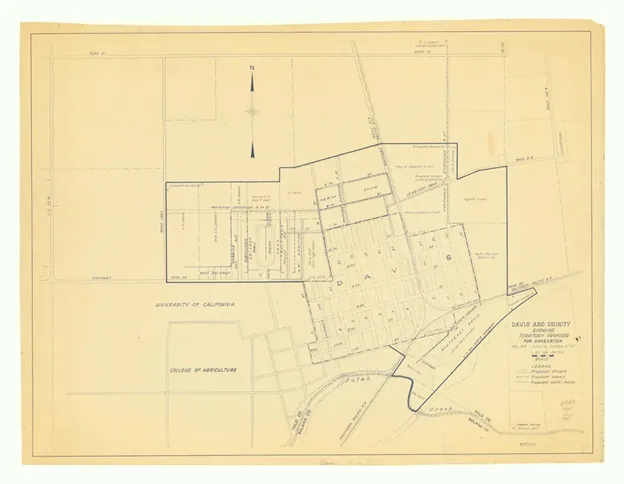

Davis itself also fell victim to this. Whereas our downtown was originally nucleated upon the train station, in the later decades we added significant amounts of single-family housing on all sides, and never once thought about whether we should be organizing the layout of those urban expansions around the need for transit.

The map above shows the initial extent of that first horizontal expansion in the 1920’s. You can see the compact existing limits essentially around downtown, as well as the proposed expansion.

Zooming out, the image below shows those two initial footprints of our city on top of the modern map. (The white circle indicates a half mile radius centered on the train station downtown.)

Davisites sometimes talk about our city being “small” and “bike friendly,” but in reality, we are without a doubt already a sprawling and almost entirely car-dependent city, and have been since the 1960s.

What is worse is that with so much land committed to very low-density housing, it is almost impossible to retrofit such a suburban landscape to one that is more sustainable. Once property lines and streets are laid out and built, and small lots sold to different owners, it’s very hard to change usage types without breaking out the bulldozers in highly traumatic ways. So in most cases, the damage is done.

Which brings us to the crux of this challenge:

- We have already discussed in a previous article the variety of reasons why it would be irresponsible for us to perpetuate this unsustainable pattern of low-density sprawl by approving any more car-centric developments on our periphery;

- We nevertheless have a variety of other reasons for us to want to grow our housing supply dramatically: Environmentally, economically, socially and morally;

- While infill opportunities are ideal, there aren’t nearly enough of them to move the needle; not for our next-cycle RHNA obligations, and not if we want to repatriate even a fraction of 23,000 inbound service workers / teachers / university staff that commute in every day;

- Doing “nothing” and just letting the housing growth occur in adjacent cities doesn’t mean there are no traffic impacts; it just makes the commutes longer for those who work in town but can’t afford to live here. And that also increases greenhouse gasses that we all are affected by.

- Conversely, adding to the local inventory of detached single-family houses will DEFINITELY make traffic worse in Davis. That’s because any detached house here will sell for at least $700,000, and our city is not growing enough jobs that pay the salaries necessary to afford such prices; so those new residents will likely be working out of town and adding to the existing rush hour commute traffic of 18,000 outbound workers as well.

Bottom line, we need to find some other way of developing on the periphery that isn’t just more car-dependent sprawl. We need to build in a more sustainable way and try to find a way to REDUCE traffic in the long run.

Let’s talk transit-oriented development

Here is where we get to the good news, because such a sustainable option IS possible here in Davis for developing better housing on our periphery. All that is required is getting back to the “streetcar suburb” model that existed before the advent of the automobile.

This is not a new or untested concept. And the basic concepts behind it are so universal among the various urban planning experts that they end up coining their own terms to talk about basically the same things:

- “Walkable cities”

- “15 minute cities”

- “Transit Oriented Development”

- The “LEED-ND” Rubric

These are all merely re-packaging the same handful of successful planning concepts, and they all quite directly involve rejecting the assumption that “everyone will drive in a private automobile everywhere for everything”

The universal starting point in all of these philosophies is to think of transit systems FIRST: Think of ways that you can allow people to navigate your development without resorting to a personal automobile.

That means designing around transit lines primarily and then putting a heavy emphasis on creating VERY safe, and well connected bike lanes that are not just stripes of paint on otherwise automotive corridors.

As urban planners have figured out how to do this well, a number of best practices have emerged:

- Transit occurs along corridors, in lines that need to be relatively direct in taking people to important employment and shopping destinations.

- People tend to choose transit over driving, especially when doing so is FASTER than car travel. So the transit service needs priority: dedicated transit right-of-ways and signal priority when transit shares streets with cars.

- Transit is more cost effective when there is a larger ridership base of people within ¼ mile of stops and where the transit goes to within ¼ mile of the destination. So planning for moderately dense and compact “walkable” neighborhoods and commercial districts all along the transit lines is also important.

What emerges from this set of needs is the concept of Transit-Oriented-Development (TOD), which ends up looking like a plan for a transit line, including proposed stops along that line, and plans for what kinds of housing, jobs, and services can be located at those stops. It is an integrated, high-level plan for a city based on transit service as well as pedestrian and cycling access.

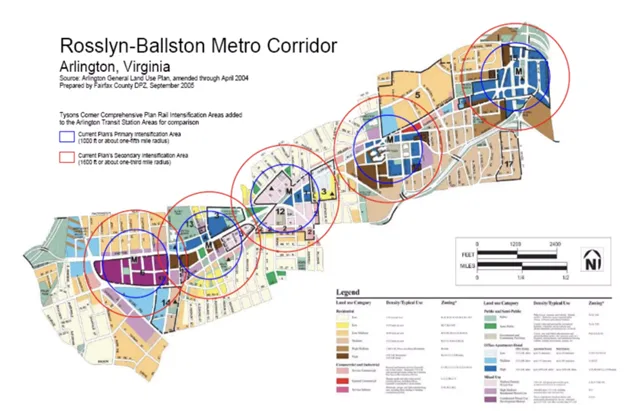

There are many examples of where this kind of alternative thinking has paid dividends, and the plans all take roughly the same approach: it is a “string of pearls” sort of city planning where the line is established first, and then stops are planned, and then neighborhoods are designed around those transit stops.

Here is an example of “streetcar suburb” planning outside of Washington DC… ( only here, the streetcar is the DC Metro)

There are a number of projects like this around the world where a transit-oriented approach has been used to create very attractive, even popular, new neighborhoods on the outskirts of larger cities without reliance on car infrastructure. And several cities in the United States have recently followed suit. Here’s an example from outside Portland, Oregon:

Transit from Scratch

For many reasons, Europe has lots of great examples of transit-oriented towns and cities, and, while we are not proposing to copy them exactly, there are models and principles we can learn from.

One great role model for us should be Freiburg, Germany, which is also a university town that has a significant amount of bikes. There is a great video about it HERE, and if you watch that, you will get a much better idea of how comfortable, attractive, and convenient a city can be when transit comes first, bikes second, and cars last.

In Freiburg, they make it simple: They do not permit ANY construction of housing that is not within walking distance of a transit line. But Freiburg had many local streetcars before the automobile arrived on the scene, and though the city was destroyed in WW2, they chose to keep their public transit rather than re-build for the automobile.

The United States, in fact had, many suburbs served by streetcars in the first half of the 20th century, but a concerted effort by the oil companies and the rising popularity of the automobile caused this form of transit to largely be removed (tracks pulled up) in the 1940’s. You can watch Disney’s “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” for a humorous take and/or read From the Archives: Did Auto, Oil Conspiracy Put the Brakes on Trolleys? – Los Angeles Times for a more complete account of this chain of events.

Most of the City of Davis, on the other hand, was developed into car dependency after the rise of the automobile, and the only “transit” system we have (Unitrans) is largely focused on moving students to campus. It has never been intended to be a generalist service to the citizenry of Davis.

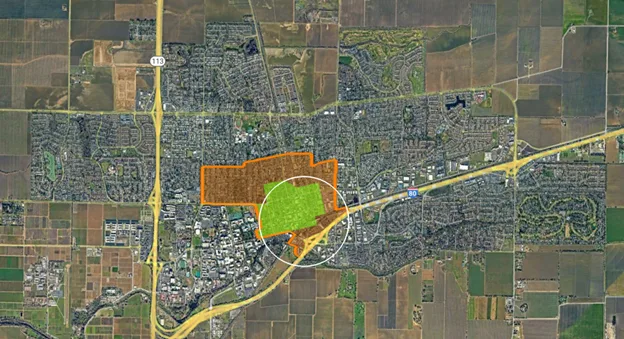

Trying to lay out a more typical transit service on top of a city made for the automobile is normally pretty difficult because the streets are rarely designed for it. But at the moment, we have a unique opportunity: there is a string of properties bordering an existing primary automotive corridor that have been submitting plans for new development: Village Farms, Shriners, On the Mace Curve, and the property known as the Davis Innovation Sustainability Campus (DISC). Taken together, and if developed with sufficiently dense housing clustered near Covell, these projects could form the backbone of a new transit corridor.

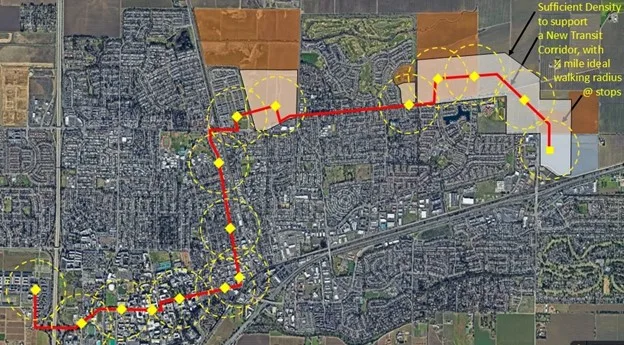

Above is a transit line concept that was first proposed in the Vanguard almost two years ago. It crosses all of the properties (highlighted) that are currently or recently under consideration for development. It would also provide incentives and direction for the properties in between who likely are considering their options for the long run.

On one end it connects these new neighborhoods to downtown and ultimately runs onto campus. The line can connect via the already moderately dense F, J or L street corridors and our Amtrak station along the way..

On the other end, it connects to the previously proposed innovation campus (DiSC) site, which is still likely the most sensible spot for additional commercial development to serve our local economy, and could serve as a “business district” for our city.

Note as well that this line would make AMTRAK a much more viable mode of extended transit for Davisites, since those within walking distance of this line do not have to drive their car to the train, and inbound travelers would be able to easily access campus and much more of our city.

What about bikes and E-mobility?

We have had to edit out a discussion of bikes from this article as it simply got too long.

We believe that E-Bikes have definitely raised the potential for Davis to transition from being a merely “bike friendly” to more of a “bike centric” city, but we will discuss planning concepts for bike infrastructure as part of our exploration of alternative designs for both Village Farms and the Shriner’s sites, or as a standalone article if people express interest.

The primary point of this particular article is how to think differently if we laid out our city with transit in mind and about the particular opportunity we have at the moment to realign our concept of what the northeast corner of our city might look like if we did that.

Is high-frequency (good) transit possible in Davis?

For transit services to truly compete with automobiles for ridership, the service not only needs to connect housing density to commercial and employment destinations, it needs to be quite frequent: one pickup (by bus or trolley or streetcar or whatever we end up picking) every 15 minutes at the very least.

Is such a service economical in “small town” Davis?

There are multiple answers to that question.

- Yes, it is economical. We picked the target density of 20 units per acre in our previous article partially because it is a threshold housing density that makes trolley / streetcar systems like this cost efficient. More people within walking distance of the transit line means more people that line can efficiently collect which means more ridership.

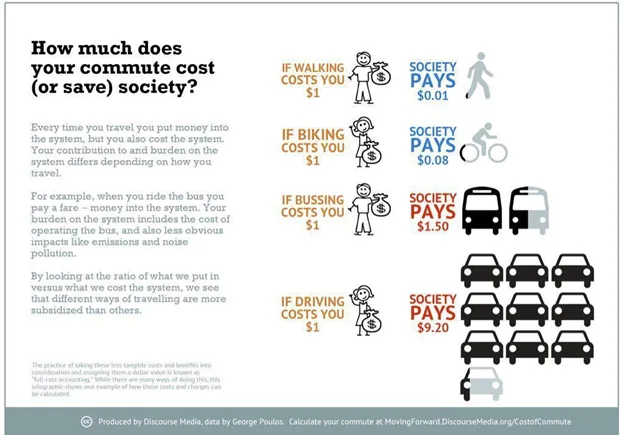

Wondering if the transit service pays for itself ignores the fact that the alternative (private car transit) is entirely subsidized, and to a much greater extent than transit could ever be.

We have become quite entitled societally to expect the government to provide us with well-paved roads leading everywhere we want to go, plus we expect free parking in lots and curbside that take up 25% of our urban land. We see that as our right. Do we ever question whether that expense is justified?

The following infographic makes this point pretty well:

If we really care about reducing VMTs and mitigating traffic, we should be willing to divert highly inefficient investments in car infrastructure into investments in bike infrastructure and transit.

Neighborhood Centers

The last high-level concept to discuss as we are talking about transit-oriented-planning is how the concepts of the “15 minute city” and “walkability” overlap with the practice of transit-oriented development.

Think for a second, about your current grocery shopping experience.

Most Davisites drive their cars to a shopping center that has a large parking lot out in front of it, in the “strip mall” configuration. Consider this picture of Oak Tree Plaza taken from Cowell Boulevard:

If a transit line dropped you here, you would still need to walk a hundred yards through a parking lot to get to the stores.

Contrast that shopping center with the Davis Commons, which is part of the much more walkable fabric of our downtown. Yes, there is a parking lot here, but it is behind the stores, creating a bike and pedestrian-friendly place up front where you can frequently see people eating outside and children playing.

This is a minor change simply in terms of “where do we put the parking lot” but it makes a large difference in terms of how well we cater to people walking, or taking transit. So transit oriented design means taking the design of the neighborhoods around the transit stations into account as well. It is not enough to just drop people off into an otherwise car-centric landscape.

Best practices for TOD include the development of “neighborhood centers” at many of the stations along that transit line. If each stop is a bulls-eye along the transit line, as you saw in the Rosslyn-Ballston example above, you will want the highest density uses in the center of that bullseye tapering off to lower-density uses further away from the stop.

This creates a “mini-downtown” kind of feel: a nucleus for the local neighborhood and a place to shop and to gather socially. An example of such a neighborhood center is visible in the Orenco Station picture above and there are a variety of other successful developments also using this model.

Not every transit stop needs such a neighborhood center, but they should at least be distributed along the line so that no point on the line is very far away from these kinds of everyday / community spaces.

Conclusion:

The peripheral properties currently considered for development in the Northeast corner of our city represent a precious opportunity: An opportunity to reject the failed pattern of car- centric suburban sprawl, and embrace a much more sustainable model of transit-oriented development.

It is rare for an established city to have an opportunity like this, and we will not likely have it again. If we want to provide the housing we need AND see our traffic and parking situation improve (not worsen), this is really the only way to do it.

The development teams for both of the peripheral projects have a very specific job: They want to win a Measure J vote and provide whatever housing they can. But that vote creates an incentive for them to not want to rock the boat—to not propose anything that the community might see as controversial. So they are sticking to just producing “more of the same” suburban sprawl… the same kind of housing that urban planners already know is a mistake.

On the city side, because of Measure J/R/D and the lack of a general plan update, we have largely abandoned any long-term civic master-planning function, and so the ideas proposed by the developers are going to be the ONLY ones that see the light of day.

This is probably the worst possible way to plan a city, and this is why we in the community need to be stepping up to ask for something better. It isn’t going to come any other way.

We have a real and rare opportunity to implement a vastly superior urban planning concept and we have time to get it done. But we will lose that opportunity if we allow any of these projects to be planned without putting transit first.

The Davis Planning Group

Alex Achimore

David Thompson

Anthony Palmere

Richard McCann

Tim Keller

Count me in.

I haven’t read this yet, but I fully agree with the title — and this concept fully is NOT happening. We, as Davis, are already the Coyote in Roadrunner: off the cliff, suspended in mid-air, and about to fall.

So eager to build baby build, that we are willing to build wrong.

The key is the map shown — basic route for a transit and bicycle corridor is correct in it’s general coverage. There are some details that should be refined to improve it, but it is very close to the route concept I would draw as a professional transit planner. I have spoke to TK about some design improvements, but the basic route concept is correct.

The major key is land use design around the transit route, as the KEY to project design. Design very high density around the transit route, medium density further away, and low density such as single family houses furthest away. This need not be gr

But land use planning around a transit route is MOOT since there is no key transit route that developers are being asked to build around. So we get a series of auto-centric blobs with an entrance on Covell/Mace.

And the Coyote falls . . .

As I’m sure you would be the first to point out: drawing lines on a map does not create a transit system. There are going to be LOTS of people at the table, and there are lots of ways we can design the service, and the service itself is likely to evolve over decades and there are a lot of detailed small decisions that are going to be important.

At this point in time is to point at the horizon and start marching in the same direction, stating that this is the way we want to go.

How we get from this as a concept to the city embracing it formally and developers designing their projects around it is really the challenge. I think that perhaps the immediate first step is that all of us need to submit comments to the VF Draft EIR process asking for a Transit-oriented scenario. (?)

From article: “Doing “nothing” and just letting the housing growth occur in adjacent cities doesn’t mean there are no traffic impacts; it just makes the commutes longer for those who work in town but can’t afford to live here. And that also increases greenhouse gasses that we all are affected by.”

First of all, “doing nothing” is not what’s been occurring in Davis. But as I mentioned yesterday, Davis has no control over what occurs in “adjacent” (nearby) cities. Start with that.

But perhaps more importantly, there aren’t a lot of new jobs being created in the city OR on campus. As such, the commute to (or through) Davis is not likely to increase much. Other than from people traveling through Davis to another destination (e.g., to avoid gridlock on I-80). Davis is “in the way” of those travelers, and is not viewed as the center of the universe.

And again, all of this seems to ignore the fact that these developments will result in an OUTBOUND migration (e.g., to Sacramento). Especially since they’re proposed for the east side of town.

Regarding transit, have you seen what’s happening regarding lack of demand for it in the Bay Area (e.g., due to telecommuting)?

If dense housing is built on the periphery of Davis, you already know “who” is going to occupy it – students (and some who commute to Sacramento). Is that the goal – to house students on the periphery of Davis in dense developments?

I have no idea what the goal actually is, other than to develop farmland.