A June 10, 2015, letter by State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson has triggered a debate over how Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), adopted in June 2013, can be used.

As the Superintendent indicates in his letter, LCFF “offers a dramatically new approach toward funding California schools,” by giving “power over the vast majority of spending decisions to those in the best position to know the needs and priorities of their districts – local school boards – while also requiring them to get significant input from their communities.”

The question that has now come forward is under what circumstance would it be permissible for the district to use supplemental grant funds to fund ongoing teacher compensation.

Two months ago, CDE (California Department of Education) Department Official Jeff Breshears said in a letter to the Fresno County Superintendent of Schools that, in a case where there is a “straightforward across the board salary increase without any condition for additional or enhanced level of service,” a “a district is essentially ‘paying more’ for the same level of service. As a general proposition, such an increase will not ‘increase’ or ‘improve’ services for unduplicated pupils, and the use of supplemental and concentration funds in this manner would not be appropriate.”

He added, “In some limited circumstances, it might be possible to demonstrate in an LCAP [Local Control and Accountability Plan] that a general salary increase will increase or improve services for unduplicated pupils. However, the burden on a district to justify use of supplemental and concentration funds for such an increase is very heavy.”

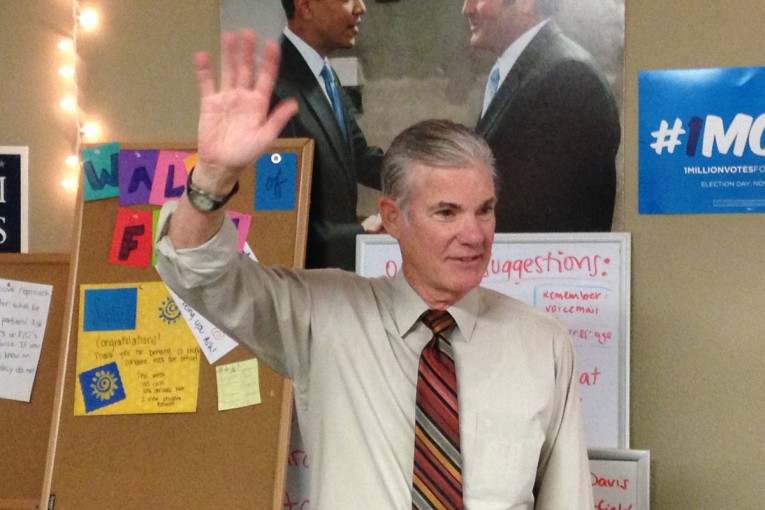

However, Superintendent of Education Tom Torlakson, a former high school science and history teacher has been a longtime ally of the CTA (California Teachers Association) during his 14 years in the Legislature and two terms as state superintendent of public instruction.

He overruled Mr. Breshears in creating a more lenient interpretation on this use of LCCF for teacher salary increases: “A district may use supplemental and concentration funds for a general salary increase in a manner consistent with the expenditure regulations and LCAP Template regulations. “

Mr. Torlakson continues, “In order to use supplemental and concentration grant funds for an across-the-board salary increase, or for any other districtwide purpose, a district must demonstrate in its LCAP how this use of the grant funds will increase or improve services for unduplicated pupils as compared to services provided all pupils. This should be in proportion to the increase in supplemental and concentration funds apportioned on the basis of the number and concentration of unduplicated pupils.”

One example is that “a district may be able to document in its LCAP that its salaries result in difficulties in recruiting, hiring, or retaining qualified staff which adversely affects the quality of the district’s educational program, particularly for unduplicated pupils, and that the salary increase will address these adverse impacts.”

In this scenario, “this district LCAP might specify a goal of increasing academic achievement of its unduplicated pupils and a related area of need for more teachers in the district with experience teaching the district’s curriculum.”

Not surprisingly, not everyone is pleased with this interpretation. Assemblymember Shirley Weber, a San Diego Democrat, has expressed concerns on behalf of the California Legislative Black Caucus about implementation of the Local Control Funding Formula.

In a letter to the San Diego Union Tribune, Assemblymember Weber wrote, “While teacher salaries are of great importance, supplemental and concentration grants are intended to achieve greater equity in our educational system by improving education outcomes for low-income students, English language learners and foster children.”

She criticizes the Superintendent for making “no connection to more equitable outcomes” in the use of those funds for salaries. She writes, “Lowering the burden of proof for salary increases only further exacerbates circumstances that the poverty supplemental and concentration grants are intended to mitigate.”

She continues, “The Legislature’s intent was clear when it enacted LCFF and the State Board reinforced this intent when it adopted regulations that these supplemental and concentration dollars were to ‘increase or improve’ services and be ‘principally directed’ to low income students, English learners and foster youth. Significant investments have already been made towards LCFF and an effective mechanism has yet to be implemented to actually track how these supplemental and concentration resources are being invested. There must be no ambiguity about who should benefit from these investments.”

In a June 18 editorial, the LA Times calls this one of Governor Brown’s “greatest and most dramatic accomplishments… his reform of the way California allocates money to public schools.”

They write: “He used the recession to hit the reset button, replacing an arcane and blatantly unfair formula with a streamlined and equitable distribution: a certain amount of funding per student, and significantly extra for those who are poor, in foster care or not fluent in English — in other words, students who need extra help.”

However, “This fairer approach will work only if school districts are committed to spending the money for the benefit of the disadvantaged students for whom it was intended, and early signs are that at least some school districts are defining that benefit broadly — perhaps too broadly.”

They write of the permission to use the funding for teacher raises: “These developments are troubling to some of the people who initially cheered the Local Control Funding Formula, and they’re right. Of course some flexibility is needed, but there is enough cause for concern that the state should be thinking about tighter, though still-sensible, controls.”

On the other hand, there may not be as much distance between the two letters on some believe. John Affeldt, managing attorney of Public Advocates, told EdSource that “the two letters reached essentially the same conclusion about the use of supplemental and concentration funds for raises – that there is, in fact, a heavy burden of proof to justify it.”

“The tone of the first was more appropriate,” Mr. Affeldt said, “but the only real difference between the two versions is a point of emphasis.”

And perhaps a raise is not completely at odds with the purpose of LCFF anyway – if the barrier to improved education rests with the ability to recruit quality teachers to more challenging environments, perhaps an increased compensation can aid in that goal.

The bottom line is that “[t]he district must appropriately document in its LCAP its basis and strategies for use of supplemental and concentration grant funds…”

—David M. Greenwald reporting

The LCFF screws Davis students in its funding formula. Now it will be used by the CTA to generate across the board teacher raises in those districts that received the most money under LCFF and create greater compensation problems in districts that did not receive the big bucks. Torlakson’s letter forms the basis for using all of the LCFF funds for increased teacher compensation in order to retain qualified teachers in Davis. All LCFF does is redistribute wealth in the state. Now parents in Davis will be subjected to more fund raising efforts and increased pressure for local school taxes to make up the difference.

My biggest problem with LCFF is that it once again takes responsibility for a child’s education away from the parents and into the hands of big brother. Parents who set the standard for their children that education is important by placing emphasis on getting good grades and developing study habits over sports or other activities are what is needed. Parents need to make sure their children do their homework, get sleep, go to school and behave in school. The problem is that many parents no longer do this and expect the school to solve these problems. Hopefully the abused that will crop up in the implementation of LCFF will lead to its demise and a return to a more equitable funding formula.

zaqzaq: My biggest problem with LCFF is that it once again takes responsibility for a child’s education away from the parents and into the hands of big brother.

LCFF has a chance of being better than the previous framework of funding, which had the state dictating where all the pots of education money should be spent. This gives local districts a chance to have a say.

Probably the reason that LCFF would fail to be an improvement is if parents and local community members failed to take a strong enough interest in what they want to see in their schools. Then the teachers’ unions and local administrators might fill the void.

wdf1… does LCFF in effect allow districts not to develop “new programs” JUST to qualify for ‘categorical funding’? Often wondered if some districts just added some program as the way to qualify for additional State funds… have no clue if I was right in wondering that.

LCFF significantly is based on the number of “high needs” kids a district has — ELL, free/reduced lunch, foster kids. The more students like that you have, the more money your district receives to serve kids in these situations. It’s hard for me to imagine, at present, that there is absolutely no need to spend any money on such kids. I can think of plenty of deficiencies that might be addressed — after school tutoring, staff social workers to connect families with community resources, onsite fulltime nurse, healthier school lunches, broader range of adult education programs for parents lacking a high school diploma, a broader range of summer school options & enrichment programs.

Torlakson is a union-owned politician. What did you expect voting for him?