Davis Assistant Police Chief Darren Pytel laid out the proposed new police body camera policy at the Phoenix Coalition’s Quarterly Chat with the Chief on Monday evening.

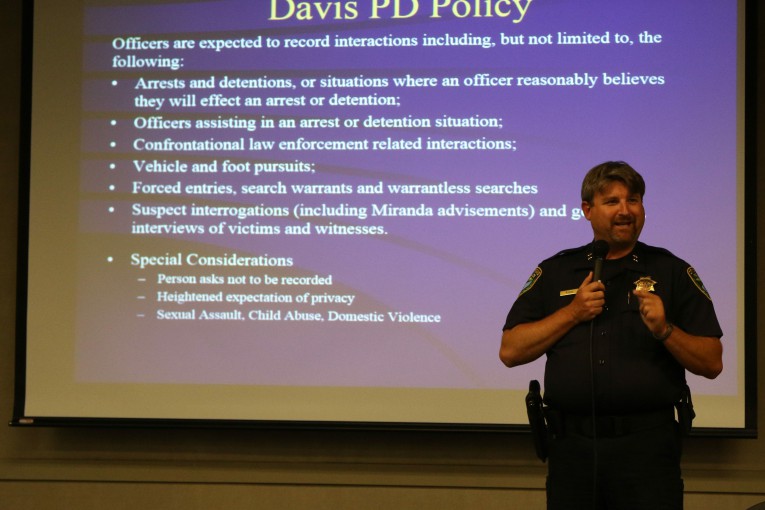

According to the new policy, which was approved by the Davis Police Officers’ Association and is being reviewed by the city attorney, but has yet to be approved by the city council, officers will be expected to record a number of interactions.

As the assistant chief explained to the small audience at the Blanchard Room of the library, in many situations that the police encounter they are not enforcing the law, and there is an expectation of privacy. However, in situations that call for arrests and detention, or situations where an officer reasonably believes they will effect an arrest or detention, body cameras would be used.

These include officers assisting in an arrest or detention, confrontation law enforcement related interactions, vehicle and foot pursuits, forced entries, search warrants and warrantless searches, suspected interrogations including Miranda advisements and, generally, interviews of victims and witnesses.

“Law enforcement related events are going to be recorded,” he explained later. “Non-law enforcement events, the transactional things we do as cops – no enforcement is being done, they’re non-confrontational – those types of things, we don’t need to record.”

“On the privacy front,” the assistant chief explained, “we have to have some allowance there. We have some special considerations. Sometimes people are going to ask not to be recorded.”

He noted that this is where they are landing with people who are undocumented. “Undocumented… don’t like calling the police in the first place, even when they’re the victims of serious crimes which we’re trying to get them to report. They don’t necessarily want video of the statement that they do provide.”

There are also areas of “heightened expectations of privacy,” while an in-car camera “can show video of a car stop,” and there is an expectation that when you are on the street or a sidewalk that you could be recorded. It is different when the police are inside someone’s private residence, there to get a quick statement from a witness. “People rightfully so have concerns about what does that mean, and how is that video going to be used,” he explained.

Darren Pytel also said that frequently they encounter people with no clothes on or in partial states of undress, and they may want to avoid video of those situations. “With video, officers need to have a little bit more discretion as to whether it is something we want to record or not,” he said.

Finally, there are cases involving sexual assault, child abuse or domestic violence, and “these are special kinds of victims or witnesses. The initial crime may be more traumatic and we need to think about whether introducing a camera or putting them on recording where other people are going to see it… whether that’s something that’s going to be a problem or not.”

There are issues of video storage that they need to consider. “This is actually a big big problem,” he said. “Every agency across the country going to body worn camera they’re suddenly having to deal with massive amounts of video and coming up with a reasonable way to store the video for a reasonable period of time.”

He estimates they’ll need more than 20 terabytes of storage. The video needs to be put on a server. “Right now we’re looking at a 79 terabyte server which is going to be just over $50,000,” he said. The information needs to go on a server for accessibility and also security. They need to have multiple backups to avoid losing multiple cases.

The storage will therefore be about $50,000 and the cameras they are looking at are around $1000 apiece, including warranties. They are looking at $100,000 and they have already set aside the money to do it.

Earlier in his presentation Darren Pytel demonstrated, showing both in-car cameras and body worn cameras that, even with cameras, there are perspectives there. The camera does not always show the exact perspective of what happened.

He explained that the public has to understand what the limitations are of cameras. Not only does the camera have to be able to show what happened, we have to understand that sometimes the camera picks up things that the officer was not aware of and did not see at the time.

Following the presentation, Assistant Chief Pytel spoke with the Vanguard.

Assistant Chief Pytel said, “The biggest concern (of having the body worn cameras) is having realistic expectations from the community that there are going to be incidents that are recorded, that doesn’t ultimately mean there is going to be video that is released right away.”

In some cases, with huge public demand, information would be released extremely quickly. “Because the video does exist, people want to make up their own minds and see it right away,” he said, “even though there’s legal justification or public policy consideration for not immediately releasing video.”

“I also think we’re going to start balancing people’s voyeuristic attitudes,” he said, where people take the position that a “juicy” story translate to a public need to see the video. “A lot of times those are going to be cases where there is a heightened expectation of privacy.”

Darren Pytel said, in terms of policy for video release, “as much as possible we’re going to follow the Public Records Act which exempts a vast majority of the video having to be released in criminal cases.”

It is the things that are non-law enforcement that cause the biggest concern. “There’s probably no justification for not releasing those video.”

They will have to resolve that issue by “not taking a video unless we’re prepared to have it disclosed.”

While this may have a bearing on the immediate public release of the video, Darren Pytel reminds the public that most of the time where there is a law enforcement action, the video will be discovered – it will just be discovered through a court of law and during legal proceedings, rather to the public through the media.

“Ultimately it’s going to be shown in court. Let’s preserve it for the investigation and let’s make sure that it’s actually used in the legally defensible manner,” he said.

However, the policy still leaves open the possibility that the police would disclose video that shows the department in a good light while withholding that which shows the department or an officer in less favorable light.

Ultimately, Darren Pytel stuck to the idea that that video would come out but it would be in the court of law or during internal investigations. “If somebody takes some sort of legal action against us, the video is going to be discovered,” he said. “Yeah we may not release it to be shown on the 5 o’clock news that night, but ultimately the video is going to be discovered.”

This is an issue that every agency is going to have to balance. Mr. Pytel explains, “You have an officer involved shooting (and) people start raising questions about whether it’s a legitimate shooting or not.” In this era, “people want instant access to it and people want to instantly be able to make up their minds [and] until they see it or hear for themselves, there is that total lack of trust.”

He said, they cannot commit to releasing the video in those circumstance. They have always taken the approach that they won’t release the video unless they legally are compelled to do so.

One of the debates is whether the police officers should be able to view the video prior to making their initial statements and writing their police reports.

It is the position of the ACLU that the officer’s initial statement should be made prior to their viewing the video to “get their natural perception of the incident in question if there’s evidence of a crime.” The subject of the law enforcement charges does not get to view the video prior to making his or her initial statement. There is concern that prior viewing of the video will contaminate the memory of the officers, as well as enable them to tailor their statements to the video.

Darren Pytel said that, while they developed the policy with the ACLU guidelines in mind, in most cases the officers will write their reports first because they don’t want to go back and watch the video, but “the officer will have the ability to watch the video prior to their report.”

He said he didn’t see a problem with them having that ability. But he did acknowledge that is one of the few points of remaining contention.

Darren Pytel told the Vanguard that the Police Auditor has not reviewed the policy guidelines yet, but they expect that he will next time he is in town. The city council will still need to approve the policies, and this matter may come forward this fall.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

A police-citizen interaction in dispute, who should be able to review the video prior to making a written report of the incident?

First, if the police can see the video early, fairness demands that the disputing party can look also. There is no possible way the City Council will approve sneak-peaks for police only. The Public Comment session on this point alone will be a free-for-all. Bring your cameras!

I have a very solid reason–based on years of direct personal experience–in support of the idea that a disputed police interaction should be seen immediately by the complainant. What people think happened–in moments of high stress and anxiety–often became highly distorted recollections when moved to the human brain. This is particularly the case when judging “the other guy.” When the complainant see how he/she behaved, compared to the police officer(s), and the language used during the exchange, the complaint comes to a humble realization, and the complaint and complainant just go away.

Body-cam departments now in operation have recorded citizen complaint dropping by as much as 80 percent. Part of this is that police officers become more “professional” aware now that everybody is watching them. Nothing wrong with that. But more often, the complaining citizens see themselves in a different light when viewed through the cold impartial lens of a camera recorder.

In the routine police/citizen exchanges, early review by the officer enhances the documentation of information put into the formal written report. Police officers are human, they don’t always remember everything the victim/witness said. Noteworthy interactions–good or bad–are also effective training tools for supervising sergeants and Field Training Officers.

A final note on cost. Discovery of police recordings will be far more prevalent in civil disputes than criminal (Most previously contested criminal cases will now be plead out because the recording is so incriminating).

The police are often neutral parties to an event that later evolved into a civil suit. When the Police Department submits this matter for City Council deliberation and resolution, include a fee schedule to help defray City costs for retrieving an copying a recording in response to a civil discovery request.

i think the policy put forth by dpd is premature at best. the policy is set up to allow the police to release the video when they deem it necessary and hold onto the video when it’s in their best interest to do.

public records law is extremely weak and the police even in litigation may be able to hold onto video as part of “personnel” files.

finally, the assistant chief shrugs off the notion that the officer can contaminate his own statement by watching the video. as he himself noted, the camera can often show things that the police officer didn’t see and miss things that it did see, both can be problematic here.

“i think the policy put forth by dpd is premature at best.”

Note the first word in the column’s title. The policy is far from maturation, so don’t worry.

While they mention a server and storage for the cameras, there is no mention of personnel to manage the server nor the extra time of documenting the evidence (since that is what this is) and what software they have for that. It will take another person or two to manage it.

Software is also not mentioned for editing unless they already have that for existing servers. This information is remarkably sparse, and I only know because I have set up video labs for law enforcement, and know some of the requirements they have for court and PR. Who is going to run all that, and how much time do they estimate these people need? $50K for a server is quite a lot in today’s world..

“Hi, we are taking video” is not much of a policy, and from what they say, many people will be able to tell an officer anything they want by just demanding the camera be shut off? That means to me they must turn it on, and when in a stressful situation, will they have it on by default, then turn it off, or will it be turned on “if they remember”?

I am not criticizing, but asking questions about how they implement this, and they are not giving me enough information. I doubt they are giving the Chief enough either. But then, the City Council won’t need much more than this?

You raise some fair points, operationally, for future consideration. The Assistant Chief was making a “first-blush “overview presentation on a concept still in equipment and policy development. Darren read his audience, regular folks. The technical aspects are, well, technical and suitable for discussion in a more focused and tech-savvy environment.

With law enforcement agencies throughout the country and beyond embracing body cams with remarkable rapidity, a lucrative market potential for suppliers is taking full notice. The associated technology is already becoming reduced in size and bulk, more refined, greater storage capacity, cheaper, and “cop-proof.’ Even a 10-thumbed police officer can’t mess it up, unless it’s deliberate sabotage, which essentially destroys one career.

Your suspicions are correct. Technicians will be retained in some capacity to administer and maintain this technology. I’d advocate that no editing capability be under the control of the police department for all the obvious reasons.

One issue that has not been discussed, at least based on this article, is the problem of police video somehow “disappearing”, and what part that plays in a possible investigation into police misconduct. See: http://reason.com/blog/2010/08/12/when-police-videos-go-missing