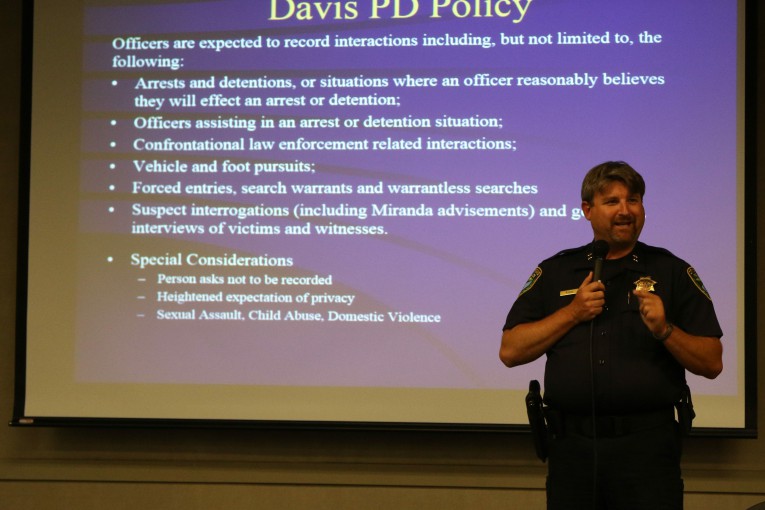

While we need to be clear – the proposed Davis Police Department’s body worn camera policy, as presented earlier this week by Assistant Chief Darren Pytel, is a good start and a much needed practice – I want to draw on several concerns that I have with the policy at the outset in hopes that they can be corrected, as the city attorney and eventually city council review and revise the proposed policy.

While the presentation by Darren Pytel focused heavily on transparency versus privacy, an important issue to be sure, there are far larger issues regarding access and release of the videos that are dominating national discussions.

This week, people were stunned when they viewed the dash-cam video showing three Gardena Police Department officers shooting and killing Ricardo Diaz-Zeferino on June 2, 2013. It was held under court seal until the judge ordered the video to be released.

It took a lawsuit from three large media organizations – the LA Times, AP, and Bloomberg – to get the video released more than two years after the death of Mr. Diaz-Zeferino. U.S. District Court Judge Stephen V. Wilson sided with them, writing “the fact that they spent the city’s money, presumably derived from taxes, only strengthens the public’s interest in seeing the videos.”

The case from Gardena raises a critical question as to whether the body worn cameras that will begin proliferating in departments in response to recent calls of transparency will result in the kind of public access that some feel is needed.

To be sure this is a debate, and with emerging technology and practices this debate figures to intensify.

“Looking at this video, you really want a police agency to be really transparent,” said Tod Burke, professor of criminal justice at Radford University and a former Maryland police officer, to the Christian Science Monitor in a recent article on the issue. “But there are privacy issues there.”

However, it was the Senior Staff Attorney for the Southern California ACLU that captures my belief: “Body cameras don’t provide any transparency if the videos remain secret, as was the case [in Gardena].”

My concern with the Davis Police policy is that is exactly what we will have – situations where something controversial occurred, and the Davis Police Department will refuse to release video, citing exemptions under the Public Records Act.

The California Public Record Act (CPRA) is notoriously weak on transparency and it is no more weak than on police records, which allow for a myriad of exemptions to avoid the release of records. An example as to just how limiting these regulations can be can be seen in a city response to a Vanguard records request.

James Martinez back in February told the Human Relations commission, “I was the victim of a malicious intentional act by a public safety officer belonging to the city of Davis.” He said the officer “caused my accident and left me on the ground without providing any type of emergency response.”

Mr. Martinez met with the Vanguard and provided a copy of a letter dated March 17, 2014, and signed by Assistant Chief Darren Pytel. The letter claims that the officer “did not intentionally turn on his spotlight and direct it towards” the man. However, it acknowledges, “That being said, when you did crash, the officer should have gotten out of his car and engaged in a more courteous/polite conversation with you to determine whether you were injured or not.”

The Vanguard filed for a public records request of the video. It is important to understand that Mr. Martinez at this point already had a sustained complaint and had a lawsuit dismissed with prejudice from the local court.

And yet, the department could legally withhold the video from the public.

The city responded, “Responsive to your request, the Davis Police Department has a video recording (in-car camera video) responsive to your request. However, the video you requested is exempt from disclosure under the Public Records Act as an investigation record and under the statutory exemption for confidential peace officer personnel records.”

They cited case law that argues, “The investigation exemption does not terminate when the investigation terminates.”

This response leads me to believe that if the city of Davis uses this standard for body worn cameras, the public will never have access to videos of this nature.

This leads to two other concerns. First, the department has the ability, using this standard, to release information that is beneficial to them – i.e. if a case like that of Halema Buzayan comes forward again and the public is outraged, they can use the video selectively to help their public relations cause, but nothing will compel them to come forward when it shows officers acting in a poor light.

The second point is that the Public Records Act is really the floor for public transparency. The department has the ability to release information that they would not be mandated to release under the Public Records Act. They would have to gain some approval from the Davis Police Officers’ Association to do some of that, but there is nothing in the law that requires the standard be the CPRA floor.

In addition to the issue of transparency there is another major issue and that is the debate over whether officers should be able to view the video prior to writing their report. This is yet another big area of concern because – as organizations like the ACLU fear – officers can watch the video before writing their report and therefore tailor their report to the video rather than independently explaining what happened.

It is the position of the ACLU that the officer’s initial statement should be made prior to their viewing the video to “get their natural perception of the incident in question if there’s evidence of a crime.”

Darren Pytel said that, while they developed the policy with the ACLU guidelines in mind, in most cases the officers will write their reports first because they don’t want to go back and watch the video, but “the officer will have the ability to watch the video prior to their report.”

While that may be true in general that police officers do not have the time or inclination to watch videos prior to writing their report, in a case they figure will be scrutinized – use of force, officer involved shooting, Tasering, other cases that figure to be controversial – the officer probably will watch the video in advance.

For a full policy analysis on this question: see the ACLU’s January piece, “Should Officers Be Permitted to View Body Camera Footage Before Writing Their Reports?”

As they argue, “If an officer is inclined to lie or distort the truth to justify a shooting, showing an officer the video evidence before taking his or her statement allows the officer to lie more effectively, and in ways that the video evidence won’t contradict.”

Moreover, it is a poor investigative practice. Police departments do not allow suspects to see the video evidence. “We don’t want the witnesses’ testimony to be tainted,” LAPD Commander Andrew Smith said. Detectives want to obtain “clean interviews” from people, rather than a repetition of what they may have seen in media reports about [the subject’s] death, he added. “They could use information from the autopsy to give credibility to their story,” Commander Smith said.

And here again we have an asymmetry. The officer would be able to view the video prior to their report, but a complainant or the accused would not.

These two issues are critical and the city needs to get them correct. We need to decide when and under what conditions video should be released and we need to set the policy very clearly on when an officer should be able to view the video.

Without these two provisions correctly in place, I cannot support the city’s police body worn camera policies.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

David,

I believe that the car cameras and audio that go with them have been available to cops for years now as a tool to write their reports when needed. Do you have any examples of the misuse of these tools by Davis cops that support your position? If a cop wants to review a taped statement to make sure he gets a important quote right from a witness or the correct sequence of events right I see not problem with that.

I just provided one example. But in the general – we don’t know, what we don’t know.

No you didn’t. Maybe you did not understand my point. Give me an example of a Davis officer tailoring his lies to conform to a car camera video or audio tape.

The police department has an obligation to prepare timely and accurate reports that are relied upon by the District Attorney. Allowing an officer to review a video or audio tape to include the most accurate information in the report is appropriate. The use of car cameras, audio and video taped statements has been going on for years. The ability of the officer to review a taped statement of a witness prior to writing the report is no different than reviewing a car camera or body camera audio of video tape to prepare an accurate report.

You’re right – misunderstood. I can’t provide such as example. I don’t think that’s the relevant point though. We know for example that Officer Slager told a lie when he gave the report about killing Walter Scott. If he knew about the video and saw it, wouldn’t he have tailored his story? It doesn’t matter that I can’t provide an example of it occurring in Davis for it to be a potential concern.

And what we don’t know, and which we can’t offer any proof to the specific matter, still gives us license to allege anything we want, with impunity, under a cloak of anonymity.

Whomever said, or legally advised to be said, that recorded videos are part of the police personnel record protection and cannot be disclosed, pulled that one out of their #%& (ok, ear). The message receiver should have retorted, “Please cite me the case decision that allows you to say that?” The State statute certainly does not. To say a recorded video translates to an entry in a employee personnel record is tortured logic and creative literary genius in the same package.

It’s correct to note that in any policy decision that materially affects the “working conditions” of an employee must be discussed with the employee through his/her bargaining agency (e.g., union). That’s the labor “meet and confer” clause briefly summarized under longstanding labor law. As a side note, this does not mean the union has to give approval before adoption, just be given an opportunity to meet “in good faith” and “confer” on the potential impact of said policy.

I have to strongly suspect the proposed body cam policy has been thoroughly vetted by the DPOA and has given its full approval for implementation. If so, it should have been said at that meeting and in a very loud voice.

I belabor (not a pun) this point because–despite this issue being discussed to the point of acute boredom–one critical player has been notably missed; police union reaction, and by extension law enforcement officers themselves. Don’t you find it odd that among the reams of papers blizzard published by the ACLU alone, not one of these legal scholars and guardians of the public safety exercise EVER felt it relevant to ask the police what they think?

Do yourself a favor. Approach the next several dozen police officers and deputy sheriffs you see driving around protecting your, ear. Phrase the question anyway you want but ask, “Would you feel threatened if people saw you while you were performing you duties on a daily basis?” Then ask a related second question, “Do you think examination of how YOU do your job would increase or decrease public perception of police that prevails today?

Publish your findings on Vanguard if you want.

Phil

“Don’t you find it odd that among the reams of papers blizzard published by the ACLU alone, not one of these legal scholars and guardians of the public safety exercise EVER felt it relevant to ask the police what they think?”

Until now, I have found your comments to be very fair and usually factually based, albeit presented as we all do, from our own point of view. However, on this I am simply not sure.

On what information are you basing the statement that “not one of these legal scholars and guardians of the public safety” has “ever” ……? Do you know for a fact that no police officers have been consulted, or is that your assumption ?

No, Tia. Staying with fact-based information, I’ve never seen a discussion on the pros/cons of body cams where the affected parties, the uniform law enforcement body, has ever been polled by the academic and legal researchers. I specifically pointed out the ACLU only because the appear to be the favored (almost exclusive) authority in public policy formulation on body cams, based on the many ACLU column posted and cited in this very forum.

And to stay true to facts, please note that I never said that no police officers had been consulted. I said that published discussions on body cams have never included compiled data from those who are expected to wear them. There is quite a difference and I’d appreciate not having my comments altered.

There may be a research study that speaks to the very matter of “street cop opinion and reaction.” I’ve never seen one but that does not mean none exist. If one is found, cite it anybody, and we will all be the wiser.

Phil

“There is quite a difference and I’d appreciate not having my comments altered.”

“not one of these legal scholars and guardians of the public safety exercise EVER felt it relevant to ask the police what they think?”

Please note that in your second quote, you made a very specific claim implying knowledge of what these researchers “felt”. Also please note that I made no assumptions on this. I specifically stated that I was not sure of your intent and asked questions rather than making accusations.

I appreciate the clarification. And we are certainly in agreement that we appreciate not having our comments altered.

“the officer will have the ability to watch the video prior to their report.”

I feel that there are two ways to handle this situation. Either both the police and the accused have the ability to watch the video prior to making their statements, or neither does.

“If a cop wants to review a taped statement to make sure he gets a important quote right from a witness or the correct sequence of events right I see not problem with that.”

How would we ensure that was his motive ? Why not have him submit his own recollections of the events first, and then be allowed to make corrections if upon viewing the tape he recognizes that he got something wrong. This is a widespread practice in medicine. Both entries are clearly visible, one as the initial entry, and one as the correction. Just last week, I made an entry error stating that a condition was on the right side when it was on the left. I opened a section on the chart specifically for revision, stated what the error had been, and made the correct entry. No harm done. Everyone realizes that humans are error prone. Why not make provision for the possibility a part of the process rather than assuming that the motives of the police are pure while those of the accused are not ?

I don’t understand the problem here. Isn’t it all about getting to the truth. If an officer has to look at a video to get to the truth than so be it.

I think there are multiple considerations. One is getting to the “truth” however, in getting to the truth, part of that is comparing the officer’s account to the video. The video does not show everything, the officer doesn’t see everything. Two, is assessing whether the officer has behaved appropriately, allowing him to tailor his report to the video, undermines the potential oversight effect of the video.

And playing the role of tailor hypothetically, take any of the published videos you want to choose. Exactly how much tailoring can anybody do to successfully contradict the cold, unemotional, impartial lens of a body camera? The claim that law enforcement officers are better tailors than cops is a myth.

Has there been a single instance where this has actually happened? None have been cited so far in this “tailor” argument. Bear in mind, with every uniform officer present wearing body cams, many angles, physical placements, and ambient light conditions are addressed capturing the same event simultaneously. Even Stephen Spielberg would not have ask for another shoot.

The notion that any officer has the ability to capture all these variables, customize the report to his/her advantage, without detection, well, you give cops far too much credit in that dimension.

come on phil – you have probably watched as many videos over the years as i have. most of them are ambiguous on key points which is why videos rarely end the debate. so knowing what the video does show can allow them to frame the issues off video in a more favorable light. would you really allow a suspect to watch a video before they make a statement? maybe if the video were indisputable, but rarely they are.

BP

There is no problem at all if you start by making the assumption that every law officer’s only motivation is “to get to the truth”. Unfortunately, I do not believe that this is true of all law officers. I have met some here in Davis that I would trust implicitly. I have encountered police in adjacent communities who I would not trust as proverbially far as I could pick them up and throw them having been directly lied to.

Darren Pytel, who is amongst those I would trust, has told me personally that there are circumstances in which police officers as part of their job are allowed to lie. How do I know that some police officer at some time will not see filling out his report as one of those allowable circumstances ?

Calling a person a liar is easily–and often–said. Like many things, 50 shades of gray go into what is exactly a lie and the person making the remark is truly a liar. “Do I look fat in this dress” has only one recommended reply, and a mis-truth remark is a viable option to preserve domestic tranquility.

The police have permission to lie remark has been mentioned before, and understandably disturbing in its application because it could mean that law enforcement officers lying is a norm of some degree or another.

Possibly the situation did not allow Darren to expand on what instances must be present for officers to deliberately lie and be allowed in any review to be permitted to do this. With no pretense or suggestion that I’m authorized to speak for anybody, and particularly Chief Pytel, I’ll offer the ONE instance where cops can lie and be given a pass for doing so.

Pursuant to a criminal investigation and particularly in an interrogation circumstance. An investigator can say, for example, to a suspect, “Any reason you can give why your fingerprints were found on the murder weapon?’ when no fingerprints existed. It’s a trick question and deceit was used to induce an admission or confession. This notion has been challenged multiple times in appellate court and still remains as a law enforcement tool.

That’s it. No other circumstance can a law enforcement officer lie and receive any kind of immunity, legally or administratively. Never is any person “allowed” to lie under oath. BTW, attorneys also have a license to lie to protect the client in select circumstances. It’s a generous application of “attorney/client” privilege. Likewise, privileged communication involving physicians and clergy. A bit more complicated to describe, and extraneous to the topic at hand.

Just like the 50 shades of gray when saying someone isn’t guilty because they plea bargained.

barack you really should read this:

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2014/nov/20/why-innocent-people-plead-guilty/

While we are at it, I think all teachers should be videoed while doing their job. That will help us eliminate some of the crappy teacher performance, the bias against certain students and also help reduce the number of employee mistakes.

And also, I think all the work-related communication of public-sector employees… especially including IRS employees and politicians, including emails, should be part of the public record. And any politician that is involved in any way with tampering with, or destroying, any communication that should be part of the public record… especially when those communications were connected with the death of people… should be brought up on criminal charges.

Frankly

I am not sure if you are being sincere or sarcastic, so I will assume sincerity.

We have actually begun video taping as an important learning tool in medical training and ongoing leadership performance assessment.

Medical students are now routinely taped in actor as patient interactions which provides them with invaluable information about how their interaction with the patient actually allows them to gain or prevents them from gaining critical information from the patient and allows them to see how their “bedside manner” affected the interaction either facilitating or inhibiting the formation of the kind of rapport that has been shown to be associated with better medical outcomes.

Likewise, identified potential physician leaders are now undergoing videotaped interactions to see which communication strategies turn out to be effective and which are alienating or block effective communication. During a recent conversation with one such up and coming leader, the comment was made “I had no idea how much I interrupted. I interrupted others constantly and I have always prided myself on being a good listener.” We frequently believe that we act in a positive manner when in fact, when viewed through the impartial lens of a camera, we see ourselves in the not always so flattering light of how we are in the real world rather than the filtered world of our own perceptions. My only regret in this regard is that this was not available to me when I began the administrative portion of my job over 10 years ago.

However, I do not know why you are limiting this to the public sector. Why should the kind of transparency that you are advocating not apply throughout the public sector as well. The public is just as dependent for our health and safety on the actions of private firms such as those providing our foods, medications, automobiles, and obtaining and transporting our fuel as we are on the public sector. Why not have transparency for all ?

I think you subconsciously answered your own question as evident by the error replacing the word “private” with “public”.

Frankly

And while that may be a cute turn of words, I do not believe that you have addressed this very valid point at all.

I know that some people with a left-leaning worldview struggle with the principles of private and public. But if you are private, tax-paying entity, you should have certain professional freedoms greater than what the public sector is entitled to. Unfortunately, it is all bass ackwards these days. Politicians and government bureaucrats hiding and deleting information and demanding a level of professional privacy that they don’t even extend to private citizens that fund their professional existence. I’m cool with cops wearing a camera, but then I would expect other public servants to do the same.

Sorry Phil, You’re spouting the company line here and it’s bs. I have been involved in a project for a couple pf years where all of the participants wear GoPro cameras and many have less obvious backup cams, as well. We encounter all manner of people and situations in our canvassing and wear the gear for documentation purposes. Cops invariably demand that we not record them, frequently citing non-existent laws and threatening crew with arrest. They wouldn’t make all that fuss if they were on the up and up, now would they?

Cops will do everything they can to cover themselves and their brothers and sisters in blue. The culture is so corrupt as to be beyond salvage.

Possibly some cops might protest about the cameras but to say that they do “invariably” I have to say you’re spouting the activist line here and it’s bs.

In several chance encounters with police working in public places in the last two years, I have been ordered to “stop filming” in every instance. I have refused in every instance, because that is my right and no one’s privacy, except the cops’ has ever been in question. Because I am old and white, the cops generally give up and leave me alone in short order. There are literally tens of thousands of these encounters well documented on the web. Cops want to operate without oversight because they cheat and lie as a matter of business. It is only because of the camcorders’ ubiquity with under 40s that many of these longstanding abusive tactics have become so well known.

;>)/

“@PC — And playing the role of tailor hypothetically, take any of the published videos you want to choose. Exactly how much tailoring can anybody do to successfully contradict the cold, unemotional, impartial lens of a body camera?”

I am rather baffled that you cannot see this. A single angle cannot show all.

When the Pepper Spray incident occurred, I started out purposefully neutral. I had friends who were injured, and also I knew it was possible they provoked the incident. The famous tapes were played millions of times, but they didn’t show the lead up or the aftermath or multiple angles. I interviewed multiple people who were on the Quad and got the same story. I went by the campus police office and finally talked to the shift leader who gave me little but made one statement that turned out later to be untrue.

I spent hours for several evenings searching through posted vids, and finally found a tape taken from a guy in tree showing the officers in riot gear advancing on the Quad. One officer went up to a person standing next to a disassembled tent, exchanged words, and the officer pushed him over backwards onto the tent. Without that video, I would have have no definitive evidence that the aggression was started by the police, and not previously started by those assembled.

Where there only one pepper spray video, an officer involved could say those assembled started the aggression. With only one angle and/or one timeframe, an officer could tailor their report to what is shown.

Frankly

“you should have certain professional freedoms greater than what the public sector is entitled to.”

On what are you basing this statement ? Do you believe that citizens in private business are invariably more honest or honorable than those in the public sector ? Why do you believe that they “should have certain professional freedoms greater than what the public sector is entitled to” ?

Phil

“Possibly the situation did not allow Darren to expand on what instances must be present for officers to deliberately lie and be allowed in any review to be permitted to do this”

Darren did explain to me in detail the instances in which a police officer could justifiably lie. And previously I had been lied to under other circumstances than those he presented. This leads me to believe that police can ( whether legally or not) and do lie just as do citizens who are not police. It would be nice to believe that those whom we trust to always act in accord with truth and the highest moral standards, ( police, doctors, nurses, priests, politicians) do not always live up to those expectations. Despite what we might prefer to believe, these people are human just like all the rest of us and subject to the same imperfections, weaknesses, and sometimes, yes, lack of honesty.

On your last sentence, that is one observation on which we can all agree. Philosophers several thousand years ago made the first discovery.

PhilColeman: “BTW, attorneys also have a license to lie to protect the client in select circumstances. It’s a generous application of “attorney/client” privilege.”

Please explain/cite the legal ethics canon or laws that permit an attorney to lie on behalf of his client.

CA Ethics Rule 5-200 Trial Conduct – “In presenting a matter to a tribunal, a member: (A) Shall employ, for the purpose of maintaining the causes confided to the member such means only as are consistent with truth;…”

Business & Professions Code 6106. “The commission of any act involving moral turpitude,dishonesty or corruption, whether the act is committed in the course of his relations as an attorney or otherwise, and whether the act is a felony or misdemeanor or not, constitutes a cause for disbarment or suspension.”

Business & Professions Code 6068. “It is the duty of an attorney to do all of the following: (d) To employ, for the purpose of maintaining the causes confided to him or her those means only as are consistent with truth, and never to seek to mislead the judge or any judicial officer by an artifice or false statement of fact or law.”

Sure, this is not a topic that the California Legal Profession that has escaped the legal profession’s scrutiny before. But first we’ll easily dispense the First and Third cited passages above. Items One and Three, note the exclusionary wording, “to a tribunal,” and “mislead the judge or any judicial official.” To be sure, judges don’t like being lied to and particularly by an “officer of the court.” But these “don’t lie” admonishments One and Three apply to attorneys only while in a court of law or administrative hearing.

Now, the more sweeping B&P Section 6106, which gives the superficial appearance of applying to attorneys in any circumstance. Not true, at least in past ands current practice.

A well researched law review article is attached below, which is on point to ethical allowances for attorneys to lie. Included are Supreme Court case rulings on attorney obligation to tell the truth, or not. Note there was at least one attempt by the California Bar to be create more precise in the wording and exception of the B&P 6106 provisions But prevailing legal sentiment is to leave it as it is. A careful reading of this well researched and presented discussion of ethical lying should answer any lingering questions, if not concerns.

http://www.lacba.org/showpage.cfm?pageid=12981

Note the following line in that article you cited, which I also read before you referred to it:

“Of course, the Rules of Professional Conduct do not advocate attorneys to lie, but their studied silence on the issue may INCLINE attorneys to advocate for their client’s interest with INDIFFERENCE to a no-less-compelling interest that lawyers conduct themselves consistent with standards of truthfulness.”

I would strongly argue (and I believe I would be correct in my assessment) that the Rules of Professional Conduct and the Business & Professions Code in regard to attorneys DOES NOT ALLOW ATTORNEYS TO LIE. If attorneys choose to lie, IT IS UNETHICAL ACCORDING TO THE LAW. If lawyers are not punished for lying, it is because the legal profession is set up in such a way that lawyers guard their own (through ethics committees made up of lawyers, courtroom judges that are lawyers), much as doctors do.

You are basing your argument solely on the powerful wording of 6106, which is an indisputable high standard of truth requirement for practicing attorneys. One can say this an ethical standard for attorneys to follow in being truthful at all times, and I’ll agree.

Unfortunately you are fishing in the wrong pond. The article spoke extensively on the ruling law, which has superior power and enforcement authority to any ethical standard. Perhaps you did not note in your initial reading the phrase describing appellate courts recognize statutory “safe havens” for attorney deceit in litigation. That’s a legally sanctioned, Supreme Court approved, allowance for attorneys to be deceitful in select circumstances. It compromises, if not supplants, the 6106 ethic standard. As the article notes, and I repeat here again, forces in the California Bar wanted to amend the 6106 ethic standard to gain more conformity to ruling case law, but failed in their efforts.

The article says the following:

“The courts have also recognized broad statutory safe havens for deceit in the litigation arena, such as the seemingly absolute mediation privilege, as the supreme court has recently affirmed in Cassel v. Superior Court, 51 Cal. 4th 113 (2011) where “[a]ll communications, negotiations, or settlement discussions by and between participants in the course of a mediation…shall remain confidential.”

I do not read Cassel v Superior Court as ALLOWING LAWYERS TO LIE. It just does not permit any sanctions for misbehavior occurring during mediation by affirming that anything said in mediation remains confidential. That is not the same thing as saying a lawyer is somehow PERMITTED TO LIE UNDER THE LAW. Attorneys are ethically supposed to be truthful at all times. They are not allowed to lie. But unfortunately because lawyers sit in judgment of lawyers, they protect their own, and they do it in a number of ways, by refusing to hold accountable lawyers that do lie. But that is a far cry from saying lawyers are ALLOWED TO LIE IN CERTAIN CIRCUMSTANCES. IN FACT LAWYERS ARE NOT PERMITTED UNDER THE RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT AND the BUSINESS & PROFESSIONS CODE TO LIE.

PhilColeman: “Pursuant to a criminal investigation and particularly in an interrogation circumstance. An investigator can say, for example, to a suspect, “Any reason you can give why your fingerprints were found on the murder weapon?’ when no fingerprints existed. It’s a trick question and deceit was used to induce an admission or confession. This notion has been challenged multiple times in appellate court and still remains as a law enforcement tool.”

I have known of particular cases where police abuse this privilege of being permitted to lie to obtain confessions (cannot give specifics). Remember Monica Lewinsky? She was surrounded by something like 20 FBI agents and taken to a room somewhere to be questioned. What was she, 20 years old at the time? When the prosecutor was asked by reporters if Monica Lewinsky had been “free to leave” rather than answer questions, the prosecutor said certainly she was always “free to leave at any time”. Really? IMO that situation was a clear abuse of power. No one in their right mind would have thought they had the “right to leave” in similar circumstances. Not to mention who knows what lies the police told Ms. Lewinsky behind closed doors, e.g. “no you are not free to leave”. The sheer coercion of the situation itself was enough to make her believe she could not leave.