By Andrea Woods and Jocelyn Rosnick

On April 11, Hamilton County police in Cincinnati, Ohio arrested Ashley Foster in a Target parking lot on charges of trafficking heroin. Foster was with her two young sons, one of whom was only eight weeks old. Foster was taken into a police car, sobbing, while her baby screamed. But because the warrant for her arrest was based in nearby Brown County, Foster sat in jail for five days waiting to be transferred and was kept in the dark about what was happening to her and even of what she was accused. The consequences of her being held pretrial without explanation were tectonic: Her kids were taken by the county department of jobs and family services, and she lost her job.

And it was all because of a mistake.

It wasn’t until after Foster spent five days in a cage that officials realized they had the wrong woman. Once Foster was transferred to Brown County and spoke to a police officer, he immediately realized he had the wrong person. Foster suffered considerable hardship and heartache based on law enforcement’s error, but no one offered an apology. And a family services worker still scanned her home before allowing her children to return.

Foster was wrongly pulled into a cycle of perpetual criminalization that is all too familiar in our nation. And though not every case involves mistaken identity, Foster’s case reiterates some of the core evils of pretrial incarceration: an ordeal we subject millions of people to each year in America.

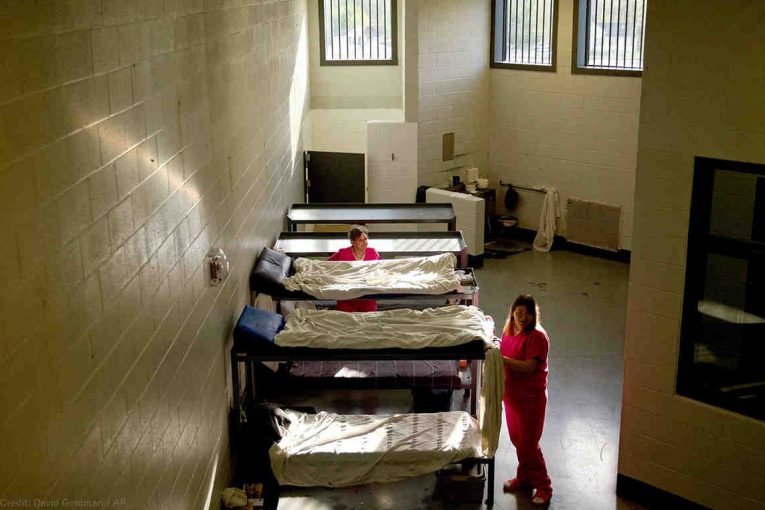

Like Foster, people incarcerated immediately after arrest cannot care for their families or maintain work responsibilities.  Others struggle to attend to their own medical treatment, or face violence in jail. From jail, it is difficult to get information to defend against one’s charges or meet with a lawyer. In Foster’s case, the jail holding her couldn’t or wouldn’t provide her with any information about her case, charges, or next steps.

Others struggle to attend to their own medical treatment, or face violence in jail. From jail, it is difficult to get information to defend against one’s charges or meet with a lawyer. In Foster’s case, the jail holding her couldn’t or wouldn’t provide her with any information about her case, charges, or next steps.

It is no wonder, then, that pretrial incarceration leads to such devastating outcomes. Controlling for all other factors, pretrial incarceration is the single greatest predictor of a conviction. Pretrial jailing is associated with a higher likelihood of getting a jail sentence, and a longer sentence. Worse still, pretrial incarceration doesn’t serve the basic purposes we generally promote during this early stage of one’s case: ensuring court appearance and community safety. Quite the opposite, even one day in jail pretrial is detrimental to those interests and associated with higher rates of failure to appear in court and re-arrest.

It is appalling to consider what Foster and her family went through over a law enforcement error. Sadly, countless unknown others share a version of her story.

10.6 million people are booked into state and local jails every year in this country. In Ohio, where Foster was wrongly criminalized, almost two out of three people in jail are being held pretrial. Despite the right to be presumed innocent in the eyes of the law, many end up in jail because of unaffordable money bail or holds from other cities or counties. Many resort to any option available to end the ordeal and gain their freedom, including entering an exploitative contract with a commercial bail bondsman, or pleading guilty regardless of the validity of the charges against them. People of color suffer the worst of these harms, and at disproportionate rates.

Nationally, a third of all felony charges end in dismissal. In New York City, data shows that the conviction rate for non-felonies is 92 percent among people detained, but only 50 percent among people released right away. The aggressive charging decisions of police and prosecutors, particularly towards people of color, are well known.

Pretrial incarceration fuels our destructive, nationwide mass incarceration crisis.

Too often and in too many places, system actors are callous to the horrors of sitting in jail. This social reality made Ashley Foster’s unfortunate situation possible, and subjects countless other women—overwhelmingly women of color—to the same cruel treatment or worse. Everyone accused deserves their day in court before they are confined to a jail cell. And no one should have their children taken away without adequate individualized due process.

The U.S. Supreme Court made clear thirty years ago that sitting in jail without having had a trial should be an extremely rare occurrence. We envision a world in which at least 95 percent of all people accused of crimes are released, rather than subjected to needless and extremely harmful incarceration. We’re fighting so no one is subjected to the treatment Ashley Foster received.

You can donate to the National Bail Out fund and help free Black mothers in time for Mother’s Day here.

Andrea Woods is a Staff Attorney with the Criminal Law Reform Project and Jocelyn Rosnick is the Assistant Policy Director with the ACLU of Ohio

This happens in Davis. I had a student arrested in downtown Davis where he had gone with friends to celebrate his birthday. At the first hearing, he was ordered held, but offered bail. After a week, he finally used the family rent money to pay a bail bond company and was released. Two months later he went to court for a pretrial hearing and the case was dismissed. The officer testified that there was no evidence that he had committed a crime and wasn’t sure why he was arrested. The Judge found the student “factually innocent” and ordered that the records of his arrest be removed. But the student lost the $1200 bail money that he used to get out of jail. He had a family with infant twins at home. The student was African American.

“The U.S. Supreme Court made clear thirty years ago that sitting in jail without having had a trial should be an extremely rare occurrence. We envision a world in which at least 95 percent of all people accused of crimes are released, rather than subjected to needless and extremely harmful incarceration. ”

I haven’t seen anyone support elimination of pretrial detention. This is reasonable.

What exactly is “reasonable”, in your view?

95 percent release pretrial

Is there some kind of support for that figure (e.g., 95% don’t represent a danger to the public)?

There is actually empirical evidence from a number of jurisdictions including DC that do not have cash bail. But something else of note, less than 20 percent of those charged with a crime even end up serving time in prison – which means they are being released anyway. So what percentage of those in prison represent enough of a danger that they need to be incarcerated pretrial? I don’t know what the exact amount, but probably less than a quarter is a fair estimate.

David… please don’t use a numerical percentage as a litmus test for whether the system works, or has addressable flaws… not real…

If you are saying 95% of those arrested, where at the scene, the “suspect” was identified as “the shooter” (particularly a school shooting), should not be incarcerated until trial… can’t get there

95% of those where a rape happened (medical evidence in close to real time) if named by the victim, should not be incarcerated before trial? Really?

Talking about non-violent felonies, any misdemeanor, yeah, could probably get there.

The 95% number is insane (unless 95% are incarcerated pre trial) when it comes to violent crimes.

Just my opinion…

No. The system doesn’t work at all. People who end up in pretrial custody end up losing their jobs, they are more likely to take worse pleas and even more likely to recidivate. Finding more ways to release people pretrial is better for the system, better for them, and helps to reduce crime. Most people didn’t commit a school shooting, a rape or a murder. Clearly there would be good reason for those folks to stay in custody.

So, David, if a suspect of a bloody felony, or a sexual assault, child abuse felony, might lose their job, by being incarcerated pre-trial, and losing custody of kids, they should not be incarcerated pre-trial, (without cash bond, of course)?… Do I have you correct? You have not responded to my questions about where (or if) the line should be drawn, but you respond to nearly every question another certain posters asks, however inane…

You’re missing a key point here – the determination for pretrial detention would not be made blindly. So by implication if it’s a “bloody felony” then it is likely they would be held.

The line gets drawn based on objective risk assessment tools that are being developed.

“objective risk assessment tools that are being developed.”

Like this one?

https://www.sfchronicle.com/crime/article/Twin-Peaks-killing-raises-questions-about-11797572.php

As opposed to Clayton Garzon?

Not sure who that would be, or whether or not they are asking the same type of questions as you are. Regardless, this is an unnecessarily confrontational comment.

I am somewhat curious (albeit skeptical) regarding whether or not such ideas could be implemented while maintaining public safety.

That’s an answer. Thank you.

Note that approach is not addressed in the article.

Key words are “objective”, and “assessment”… both subject to discretionary viewpoints by individuals … and that apparently they (“tools”) do not currently exist, at least in general use.

Likely a path for ‘improvement’, but not necessarily a panacea/solution. But a necessary start, and a good initial goal…

Edgar Wai says jail’s good for her.

Edgar Wai May 10, 2019 at 8:38 pm

Happy Mother’s Day.

Yep… works on two levels…