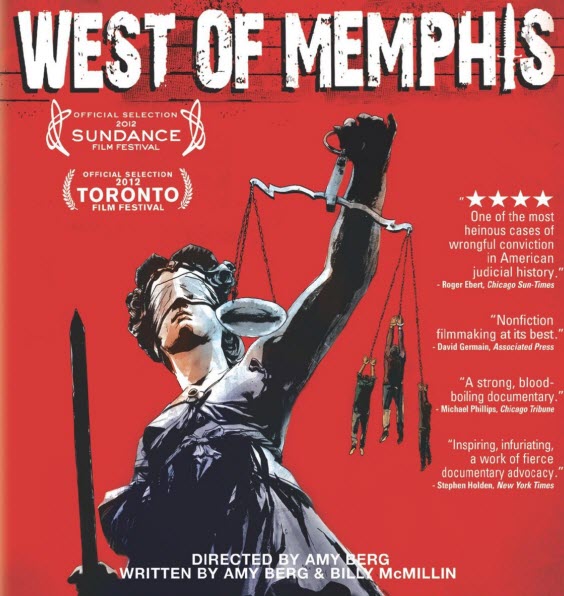

This week, I have been catching up on my rest and finally got to watch “West of Memphis,” a documentary that chronicles the conviction and partial exoneration of three young men who in 1993 were convicted of killing three eight-year-old boys.

This week, I have been catching up on my rest and finally got to watch “West of Memphis,” a documentary that chronicles the conviction and partial exoneration of three young men who in 1993 were convicted of killing three eight-year-old boys.

This was a classic case of the police in a small town, without proper training or resources, reaching incorrect conclusions about a killing. They had assumed this was a ritual killing, perhaps by a Satanic cult. One of the boys was coerced into a confession and the rest of the case stacked up against them, leading to their incarceration for 18 years.

Unlike many people in this position, the boys became the cause célèbre for rock stars like Eddie Vedder and Henry Rollins. They were able to tap into their own resources and pool it with others like Johnny Depp, to be able to hire retired crime scene investigators and other forensic pathologists to re-examine the crime, and, with the help of private investigators, re-interview witnesses.

This led to the case unraveling for the prosecution. The confession had huge holes in it, and while there was video taken of the confession, it was not taken of the interrogation. Even so, it quickly became obvious that the police simply fed him the information to make the confession.

The animal bite marks after the kids were dumped in a waterway were mistaken for ritualistic sacrifices.

A re-examination of the bodies turned up hairs that did not match the boys. Eventually, they were able to link a hair on one of the ligatures to one of the boy’s stepfather, and it became clear that all of the evidence pointed toward that man’s guilt.

And yet, in 2007, as papers were filed for a new trial including all of the new evidence, the original judge presided over that ruling and denied the request for the retrial in 2010, arguing that the DNA tests were inclusive.

However, they would appeal to the Arkansas Supreme Court which, on November 4, 2010, ordered a lower court judge to consider whether the DNA evidence might exonerate the three. They also caught a break as the original judge, David Burnett, was elected to the Arkansas State Senate and a new judge, David Laser, was selected to replace him.

As the documentary describes it, the defense and state attorney general’s office began to enter into negotiations, and eventually they reached an agreement that would mean that the prosecution could save face and let the boys, now behind bars for over 18 years, be able to enter guilty pleas to lesser charges while verbally stating their innocence.

They would be sentenced to time served and given a Suspended Imposition for 10 years, which means if they re-offend they can go back to prison for another 21 years.

This is known as an Alford Plea. Henry Alford was once accused of murder and faced the death penalty. In that case, there was believed enough evidence that a jury could be convinced of guilt. The case resulted in North Carolina v. Alford in 1970, which went to the US Supreme Court.

Mr. Alford faced the prospect of the automatic sentence of death in North Carolina at that time. He could have pled to first-degree murder and received a life sentence but not death. He appealed, arguing that he was forced into a guilty plea because he was afraid of receiving a death sentence.

In the West Memphis Three, this was a political plea, allowing the prosecutor to maintain that he got a guilty plea, while allowing the defendants to finally be released. Yes, they could have prevailed in a new jury trial, but even with all of the new evidence, it was still a huge risk – a risk neither side wanted to take.

By this point in time, the families had serious doubts about the verdicts. In the documentary, the father of one of the victims proclaimed that this was not justice.

And now we have a situation where the case is closed. The real killer remains free and cannot be prosecuted because of the Alford Plea.

Over the last few years, we seen these scenario play out over and over again.

We have seen cases where new DNA evidence emerges that apparently is not sufficient even for a new trial. We have seen cases where the confession is shown to be false. We have seen cases where witnesses have recanted.

In some cases these lead to new trials, the dropping of charges, and exoneration. In most cases it takes years to get to these points, prosecutors are unwilling to acknowledge that they got the wrong person and they fight it every step of the way.

There has to be a better way. The system is set up to protect the presumption of innocence up until the point of conviction or plea agreement at trial. That is a right guaranteed under the Constitution.

But once a conviction is obtained, guilt becomes the presumption. And that, for the most part, is how it should be. A jury trial is a high threshold of establishing a factual basis for guilt.

However, as we have increasingly seen, that is sometimes not sufficient. Juries make errors, but more often the errors are elsewhere in the system. In the West of Memphis case we have poor forensic techniques, where the prosecutor was lazy, relied on assumptions, and did not test the assumptions about the case.

They got it wrong. There was evidence that they got it wrong – the DNA, the evidence that pointed to the stepfather, the new forensic analysis that suggested, rather than a Satanic cult, that the post-mortem injuries were due to reptiles, etc.

The question is how do we protect the sanctity of the overwhelming majority of convictions while lowering the threshold for new trials based on DNA evidence, evidence of false confessions, recantations of witnesses, etc.?

This does not have to be rocket science, but the prosecutor in this case shows why this is needed. Prosecutor Scott Ellington indicated “that although he still considered the men guilty, the three would likely be acquitted if a new trial were held given the powerful legal counsel representing them now, the loss of evidence over time, and the change of heart among some of the witnesses.”

How can we get these cases out of the hands of individuals who have a stake in the case, and into the hands of some sort of wrongful convictions panel that can independently analyze cases to determine if the basis for conviction still remains?

Yes, we understand that having new trials twenty years later becomes problematic for the state, given the erosion of evidence and memory, but at the same time, these people spent years and years of their life in custody after it was clear to most reasonable people that they were the wrong men. And this is not an isolated problem – many sit incarcerated for decades when it is clear there was something very wrong with their cases.

Ultimately, these men were released from prison, but in the end, justice has not been served – not to those men and not to the victims, whose killer is still free.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

“The real killer remains free and cannot be prosecuted because of the Alford Plea.”

I don’t understand. Why would an Alford guilty plea preclude prosecuting the so-called “real killer” if adequate evidence is obtained to make successful prosecution likely?

They have a guilty plea. The prosecutor has indicated he still believes in the guilt of the three though he acknowledged he hadn’t reviewed the full case file.

But, that’s the current prosecutor’s evaluation and decision at this point. That isn’t the question. Why would an Alford plea keep a prosecutor from moving ahead on new evidence in a cold case any more that other guilty pleas or even in cases with guilty findings by juries or judges? It doesn’t seem logical.

Of course, the stepfather may be innocent (as we should presume) and the three who have been in prison may be guilty. If so, the case likely wouldn’t develop evidence on which to follow up with another prosecution.

Sorry I got pulled away from responding. So I erred in my comment, there is nothing to preclude the prosecutor in an Alford Plea from pursuing other suspects, my comment should have been more generalized to this case, that the current prosecutor seems disinclined to do so. My bad there.

“The question is how do we protect the sanctity of the overwhelming majority of convictions while lowering the threshold for new trials based on DNA evidence, evidence of false confessions, recantations of witnesses, etc.?”

I agree that this is one central question. Unfortunately, I do not see that we will achieve this goal while maintaining our current adversarial model which is based on “winning” cases and achieving convictions or conversely for the defense “getting the best deal” for the client regardless of innocence or guilt to one of determining the truth and protecting our society accordingly. Until we focus on the goal of societal protection rather than winning or losing cases, I do not see us being able to achieve this goal.

“…our current adversarial model which is based on ‘winning’ cases and achieving convictions or conversely for the defense ‘getting the best deal’ for the client regardless of innocence or guilt to one of determining the truth and protecting our society accordingly.”

I disagree with your contentions about the basis from the prosecution’s standpoint as well as the basis from the accused’s standpoint

But, you’ve observed this so many times that I think it’s your starting-point assumption. So, let’s accept this dismal view of the objectives of our system and look at the alternative you would like to use.

What process would you use to determine “the truth” and protect “our society accordingly” when someone is accused of a serious crime?