by Michaela Wallin and Sandra S. Park

by Michaela Wallin and Sandra S. Park

When a man in Binghamton, New York was restrained, stabbed, and robbed in his home, his neighbor called 911. Although he told the police that he did not know the attackers or why he was targeted, the city designated this episode of random violence as a “nuisance” under local law. Officials later informed the man’s landlord of this incident and others that led to the police being called to the property. In response, the landlord assured the city that every tenant in that building would be evicted to address this issue.

Alarmingly, this kind of story is not uncommon. Nuisance ordinances – also called crime free or disorderly house laws – are on the books in towns and cities across the country. In Binghamton, the city defines many crimes as public nuisances, such as assault, disorderly conduct, and sex offenses. All too often, when these crimes occur, the resident is the victim. Once the nuisance law is triggered, the property owner is told to address the issue or face penalties that include an order from the city closing the building. The majority of landlords respond to such warnings by removing the tenants who were the subject of a police call.

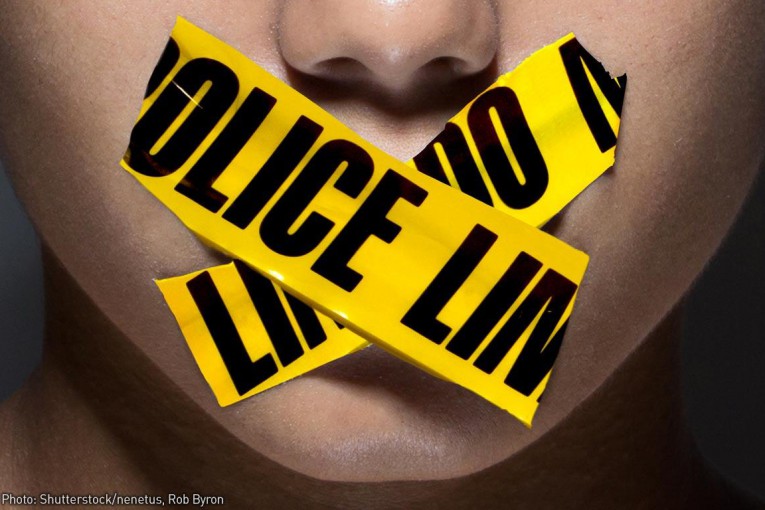

A new report issued by the ACLU, in partnership with the Social Science Research Council, reveals the devastating consequences of nuisance ordinances for victims of crime in New York and domestic violence survivors in particular.

Silenced: How Nuisance Ordinances Punish Crime Victims in New York uncovers how victims of domestic abuse are too often further victimized by nuisance laws. The report focuses on an analysis of records from both Binghamton and Fulton, NY. Though the cities structured their ordinances differently, domestic violence was the single largest category of activity that led to enforcement of both laws. Domestic violence accounted for 38% of nuisance “points” in Binghamton and 48% of incidents in Fulton’s nuisance warnings. Both cities also routinely penalized tenants who reported other crimes committed against them, including incidents of rape, theft, and assault, or sought medical assistance.

By penalizing calls to police, nuisance laws deter the reporting of crime and force vulnerable people from their homes. Survivors of domestic violence are especially impacted by these policies because they often have to call 911 in the face of crimes that occur in their home.

Another Binghamton woman was the victim of repeated domestic violence incidents and enforcement of the local nuisance ordinance when the city declared two episodes of this violence to be nuisance conduct. In the first instance, neighbors called 911 when her boyfriend threw her to the ground and began choking her. The boyfriend was arrested and the tenant got an order of protection against him. When the boyfriend returned, uninvited, he got in a fight with another person at the property, causing a police response. Although police arrested her abuser, first for assaulting her and then violating the protection order, her landlord responded to a warning letter from the City by telling officials that the “first order of action” was to evict the woman.

The documented consequences of nuisance ordinances make clear that these policies do not further their often-stated goals of community improvement. Moreover, nuisance ordinances can also be unlawful. A number of federal lawsuits, including one brought by the ACLU on behalf of a domestic violence survivor, have successfully challenged their enforcement as violating constitutional and federal protections.

Thankfully, New York has an opportunity to take action. The New York Assembly unanimously passed legislation that would protect landlords and residents from unjust application of nuisance ordinances. The Senate and Governor Cuomo should ensure, before the end of this legislative session, that no New Yorker must choose between calling 911 and staying in their home. The bottom line is that in New York, a crime victim is not a nuisance.

Michaela Wallin works on the Women’s Rights Project and ACLU & Sandra S. Park is the Staff Attorney for the ACLU Women’s Rights Project

I’m familiar with many domestic violence survivors. The reasons they do not report it, even to friends/family, let alone law enforcement, are many. A few common reasons are, law enforcement may take your kids away while investigating. Another common reason is, “If my dad/brother/friend finds out, he will want to kill the guy or at least beat the crap out of him.” Then he’ll be arrested, not the abuser. People also worry about court appearances, losing their job, ultimately losing the court case. Loss of income. They worry the abuser will be so angry, when they get out of jail after a short sentence, they’ll try to kill her. There is also the stigma of being stupid for “letting” someone hit you. People lose their support group when this occurs. If the person is bothered at their place of employment, they can lose their job. If they are bothered at home, they can be evicted.

sisterhood

Nice summary of the challenges facing those who are involved in domestic violence situations. I would like to elaborate a little more on one point that you mentioned, loss of income. It is not unusual in domestic violence cases for the family structure to be of a patriarchal nature where the man is the sole breadwinner, the woman is not “allowed” to work outside the home, has money doled out to her and may have no access to money apart from what is provided by the abuser. Thus arrest of the abuser may represent more than loss of income, it may represent a total loss of economic support of any kind. Add to this that even if the abused had familial support initially, part of the dynamic of an abusive relationship is for the abuser to cause her to become more and more isolated from any other support system and thus more and more dependent upon him.

Despite the existence of women’s shelters and government assistance programs, it is true that for many of these women, there is simply no safe, good choice.

YES. Total isolation. No way to support oneself, which, again, could cause loss of custody of her children. The woman can sometimes be so dependent and so utterly controlled, she can’t think for herself.