Recently I sat down with the mother of a man convicted in Yolo County of a crime – she believes he is innocent and, having followed the trial and read through their evidence, I believe they at the very least have a credible claim that he was wrongly convicted. The sad reality, though, is that even if he is innocent they are probably looking at 15 to 20 years before getting through the appeals process to prove it.

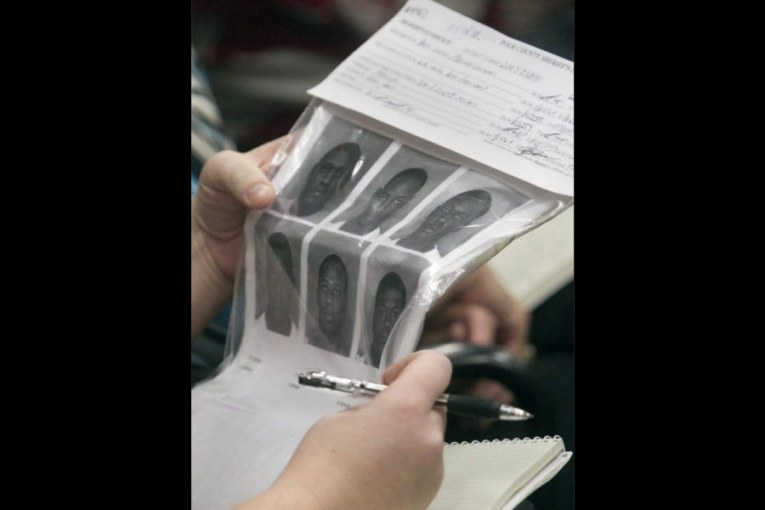

As I suggested in Sunday’s column, Justin Gonzalez’s conviction has a number of classic triggers for wrongful convictions – unreliable testimony from witnesses promised leniency in exchange for inculpatory testimony, unreliability of eyewitness identification, and probable government misconduct. An independent body might be able to review the case and question whether or not these convictions should hold.

But it will take years for the appellate system to work and, while we occasionally see a quick resolution, most cases appear to free innocent people only after decades in prison – when the injustice is impossible to realistically remedy.

There is a better way, but it would require a sea change of monumental proportions. In 2014, Yolo County followed the national pattern of creating a Conviction Integrity Unit. At the time, the Vanguard and other critics were skeptical that it would amount to anything and, to our knowledge, the Conviction Integrity Unit has never played any sort of a role in reversing a conviction.

At the time, DA Jeff Reisig stated in a press release: “A prosecutor’s role is to ensure that our system achieves justice which includes not only convicting the guilty but also guaranteeing the protection of the innocent. The creation of this Unit helps us to obtain both of these goals.”

As the office explains, “This unit will be headed by an Assistant Chief Deputy District Attorney to review all claims of factual innocence made by persons who have been convicted of crimes.“

The release goes on to explain how the process will work: “The Unit will conduct an initial inquiry to determine whether further review or investigation is necessary. The Unit will review transcripts, evaluate forensic evidence in light of new scientific knowledge, conduct additional forensic tests, interview witnesses, or conduct any other investigation deemed necessary. This Conviction Integrity process supplements the appellate process already available to defendants and is designed to avoid the possibility of an innocent person being punished for a crime they did not commit.”

Those we talked to are concerned that the standard of “actual innocence” may be too high a standard. The DA’s office notes, “The existence of a reasonable doubt does not necessarily result in a conclusion that the defendant is actually innocent, the conclusion must be that there is clear and convincing evidence that there exists a plausible claim of actual innocence in the case.”

Proving actual innocence is an extremely high threshold, which is why it takes so long to correct a mistake in the system. That is one of the problems in the system – it is fairly easy to wrongly convict someone; all it takes is a jury to believe inaccurate or even contrived testimony and poor forensic evidence, and to not properly understand the limitations of the evidence before them.

In order to correct that error, it takes proof of actual innocence which means that, while over 2000 people have been exonerated in the last two decades, many more innocent people languish in prison, possibly for life for crimes they did not commit.

But there is another way. Mark Godsey highlights the efforts of just two Conviction Integrity Units that in 2015 accounted for one-third of all exonerations by themselves – in Brooklyn and Houston. The good news is that those units work, the bad news is that the volume of people freed should be alarming because it seems unlikely that Brooklyn and Houston are outliers for wrongful convictions, and that therefore the rest of the Conviction Integrity Units are ineffective at best.

Professor Godsey in his book, Blind Injustice, which I highly recommend for its pioneering work on understanding wrongful convictions, notes that the Conviction Review Unit in the Brooklyn DA’s office, created by the late Ken Thompson, exonerated 20 inmates in just its first two years of operation. Meanwhile the CIU in Houston freed 42 inmates in 2015 alone.

Writes the professor, “No law school innocence organization, including my own, can come close to matching those numbers.”

While he describes them as “welcome and much-needed addition(s) to the innocence movement,” he also warns “the failings in other jurisdictions show that success in this area is hard to attain.”

Instead, he says “many of the other CIUs thus far appear to pay little more than lip service to the problem of wrongful convictions, because the prosecutors in charge seem understandably unable to move past their own psychological barriers to adequately reexamine old cases with a fresh eye.”

The stats are telling. In 2015, 58 of the 149 exonerations in the US came from CIUs. But, Professor Godsey warns that “58 exonerations came from the small group of CIUs that have proven to be effective.” He suggested “if every major city in the United States had a CIU as effective as the ones in Brooklyn and Houston, it would be a complete game changer.”

In 2016, the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice at the University of Pennsylvania Law School released a review of Conviction Review Units (“Conviction Review Units: A National Perspective,”). At the time, there were over 25 CRUs across the US.

In it, it has recommendations of best practices, which include that “Units emphasize independence, flexibility, and transparency in their daily operations.”

The report warns, “There is no single, conclusive measure that reveals whether a particular unit is a sincere CRU or a callow CRINO [Conviction Review In Name Only]. This is true even of the metric that most casual observers focus on – the number of exonerated individuals CRU Checklist whose convictions were vacated by the Unit.”

In a press release they note: “CRUs should ensure their independence by reporting directly to the District Attorney, installing leaders with firsthand prosecutorial and criminal defense experience who are respected within the jurisdiction’s criminal justice community, and including objective review participants from outside the DA’s office.”

In addition, “CRUs should have flexibility to deal with a wide variety of claims of innocence, providing procedural support for fact-based case reviews, reviewing each petition on its factual merits, and allowing for resubmission of a petition whenever additional credible evidence is brought to light.”

Finally, “CRUs should operate transparently, sharing information about its policies and procedures and decision-making criteria with the public and reporting in a regular and timely fashion on decisions made in cases that are granted review, as well as cases that may not be suitable for review.”

“While I don’t believe that any CRU has embraced all of the best practices listed in the Quattrone Center’s report, it’s important that we as prosecutors share our experiences with conviction review and learn from each other, and this report provides unique insights into what is useful, and what may be difficult, in launching and running a CRU,” said Brooklyn District Attorney Ken Thompson. Under District Attorney Thompson’s leadership, Brooklyn’s CRU has vacated the convictions of 19 people since Thompson took office in 2014.

“Good faith CRUs that operate with independence, flexibility, and transparency,” the report states, “can build bridges across what is too often a bitter ideological divide between prosecutors and defense counsel, and between law enforcement and the communities they serve, and restore the community’s faith that each part of the system is operating to ensure that perpetrators of crime — and only perpetrators of crime — are held accountable for their acts in ways that preserve the constitutional freedoms of all.”

As the Vanguard noted in Sunday’s column, the dataset in the National Registry on Exonerations has identified many causes of wrongful convictions: false confession, eyewitness misidentification, junk science, government misconduct, snitches, and ineffective counsel.

In the probable cases of wrongful convictions, we have spotted many of these errors, and a sincere body reviewing these convictions on a regular basis might have been able to find some of these sources of error – and call into question the integrity of the prosecution and thus the conviction.

But to date that does not appear to have happened, which is not unusual. As the units in Brooklyn and Houston demonstrate, a sincere effort is likely to find problematic convictions and undo their damage, and probably much quicker than a post-conviction appeals process – but, for most jurisdictions, that hope is fleeting at best.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

What a great article, It’s interesting to see that Yolo Counties, Conviction Integrity Unit is not following the, very reason it was put in place for. Integrity, ethical practice, in reviewing transcripts, evaluating forensic evidence and conducting further review of witnesses and their credibility?? What’s going on here?