Back in October 2010, the Northern California Innocence Project came out with a report, “Preventable Error: A Report on Prosecutorial Misconduct in California 1997–2009,” that uncovered over 700 cases in which courts had found prosecutorial misconduct during an 11-year period. One of the biggest findings was the report found that in all of those cases of misconduct by prosecutors – just six prosecutors were disciplined by the state bar.

In their report there were several cases from Yolo County cited – but one that was not, at least initially, was the case of Lawrence Miranda. Thanks to the work of the Vanguard, the Innocence Project added that to the list of cases of confirmed prosecutorial misconduct in Yolo County.

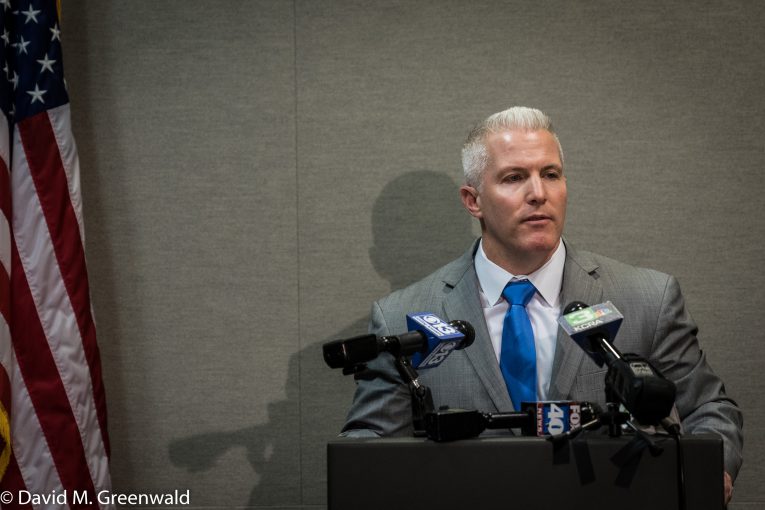

The prosecutor on that 2002 case was none other than Jeff Reisig, then a Deputy District Attorney.

A jury found defendant Lawrence James Miranda guilty of threatening to commit a crime which would result in death or great bodily injury and found he personally used a firearm in the commission of that offense.

According to the appellate court, “The victim saw the grip of the object outside defendant’s pants pocket and saw the shape of a barrel under the fabric of the pants pocket as defendant pointed the object toward her. From its appearance, and defendant’s threat to shoot her, the victim believed the object was a gun. However, when defendant and the other suspects were searched approximately two hours later, no gun was found. Nor was any gun found in the hotel room where the suspects were discovered. Likewise, a search of the area around the hotel revealed no gun. Officers also searched a barn several miles away, based upon Corrina Guavara’s statement that she had driven there with defendant, Carillo, and Avila after the three men had left Judy’s Bar. No gun was found in the barn. According to Officer Puffer’s testimony, the red car belonging to one of the suspects was found but, “to [Puffer’s] knowledge, it was never searched.”

During summation, the prosecutor, Jeff Reisig, then Deputy District Attorney, argued that the officers’ failure to find a gun did not help defendant: “(T)hat’s not decisive of the charges here, because we have a witness (Leslie) who saw (a gun), (and defendant and the others) had two hours to dispose of evidence.”

The key point is here, “Twice during deliberations, the jury sent notes to the court concerning the question of whether the object in defendant’s pants pocket was a firearm.”

After the verdicts were recorded and the jury was discharged, the prosecutor spoke with jurors outside the courtroom. The prosecutor and defense counsel had differing accounts of what happened next.

In the words of the prosecutor, Jeff Reisig: “While I spoke with the jury, (defense counsel) exited the courtroom and approached. As he approached, one of the jurors asked me if the red car had ever been searched. I responded that ‘I believed’ it had been searched by another police officer. My response was based on my assumption that with the number of police officers at the scene it would have been highly unlikely that no one searched the car. (Defense counsel) arrived at my location just as I made the above statement.”

Defense counsel Lawrence Cobb of course described it differently: “I left the courtroom to speak with the jury members who had remained. (The prosecutor) was already there speaking with some of the members of the jury, and from the content of the discussion it was apparent that he had been so engaged for some time.”

He continued, “I began speaking with (jurors) as well. asking questions about what was and what was not convincing evidence in their minds. While so speaking with the jury members, (the prosecutor) turned to me, and in a causal [sic] manner, told me, in substance, that he had received information that the car had been searched but no gun was found and that, apparently, Officer Puffer was not aware that such a search of the car had been conducted. No other information was given to me nor did (the prosecutor) tell me when or how he had learned of such information.”

Believing that the prosecutor had withheld exculpatory evidence, defense counsel made “an Informal Request for Discovery,” and received two supplemental reports, each of which stated that Officer Scoggins searched Avila’s car after the suspects were detained, and found no gun in the vehicle.

Based upon this new information, defense counsel moved for a new trial on the grounds of newly-discovered evidence and prosecutorial misconduct (withholding exculpatory evidence) which had a  bearing on the finding that defendant used a firearm while violating Penal Code section 422.

bearing on the finding that defendant used a firearm while violating Penal Code section 422.

Defense counsel argued: “[T]he fact that the car had been searched and no weapon found was highly exculpatory and, coupled with the testimony of (the victim) regarding the alleged gun, as well as the testimony of (the DJ and bar owner) that they never saw a gun, it is reasonably probable that the jury would have found doubt and brought in a not true finding on the enhancement.”

The trial court denied the motion, stating: “I do not find that there is any probability that the jury would have come to a different result regarding the firearm enhancement, even if this additional information had been presented.”

However, the appellate court disagreed.

They wrote, “Without doubt, the presence or absence of a gun in defendant’s possession following the threat was material to the question whether the object in his pocket was a gun or whether he just simulated one. The evidence showed that, when defendant and his two companions were detained two hours later, searches revealed there was no gun on their persons, in the hotel room where they were found, in the area surrounding the hotel, or in a barn where they went after defendant had threatened the victim. This left three possibilities: the gun was left in the car; the gun was disposed of elsewhere; or there was no actual gun.”

They continued, “Certainly, jurors could infer Officer Puffer would have known about it if the car had been searched. Thus, Puffer’s testimony that, to his knowledge, the suspect vehicle was ‘never searched’ tended to provide one reason for the void: the missing gun was left in the car. We find it quite conceivable that the jurors may have been influenced by this implication.”

Furthermore, “If the jurors were told during the trial that the suspect vehicle had been searched and no gun was found, this would have eliminated a convenient and logical explanation for the absence of a gun.”

They wrote, “Hence, our confidence in the verdict on the use enhancement is undermined by the prosecution’s failure to disclose this material exculpatory evidence to the defense.”

They ruled that “the prosecutor violated defendant’s right to due process by failing to disclose to the defense the existence of material exculpatory evidence pertaining to the issue of whether defendant used a firearm while threatening to shoot the victim. Accordingly, the trial court erred in refusing to grant defendant’s motion for a new trial on that issue, and the use of a firearm enhancement must be reversed.”

The story was captured in a 2006 Davis Enterprise article.

Wrote the Enterprise, “The jury convicted the defendant, and while speaking with the jury afterward, Cobb said he overheard Reisig tell jurors there was a vehicle search during which no gun was found. Cobb says he believes Reisig knew that information, potentially favorable toward his client, before the jury received the case.”

According to the Enterprise, Mr. Reisig disputes Cobb’s version of events, calling it “outrageous.” They wrote, “He said the jury never received information about a vehicle search, though a police officer mentioned while the jury was deliberating the case that police had searched a car and the area around it, but found no weapon.”

The story continued, “The appellate court ruling, Reisig said, reflected the court’s opinion that the jury was entitled to hear information about the car search in case it would have affected the verdict. He added that there was no finding of intentional misconduct or hiding of evidence, and he declined to refile the gun charge because the defendant was performing well on probation.”

“It wasn’t the best use of resources to proceed with a new trial for the use of the gun,” Jeff Reisig told the Enterprise during the heat of the 2006 District Attorney race against his colleague Pat Lenzi.

A Look At Prosecutorial Misconduct in Yolo County – Part Two

Courts Found More than 100 cases of Prosecutorial Misconduct in 2010

—David M. Greenwald reporting

Hello readers – We are in the middle of one of the most interesting and exciting election years in recent history. The Vanguard is bringing the election coverage like no one else. And we’ve brought on some additional help just to make sure we cover everything. We need to raise $1000 this month to help cover the bills. It’s a small campaign, but necessary. If you support our work – please donate a little bit to help us out.

To donate, hit this link: https://www.gofundme.com/may-vanguard-fundraiser

Reading this makes you wonder how often this stuff is happening and you just don’t know about it.

The “Baby Justice” case was a case of, if not misconduct, at the very least questionable judgement for which another innocent has paid dearly. During the time he was left free to sell meth and impregnate women in exchange for testimony ( my interpretation) he fathered yet another meth affected baby ( fact ).

The case of “Baby Justice” comes to mind. If not misconduct, at least very poor judgement was involved which resulted in yet another severely affected innocent. Frank Rees, a known meth dealer, allowed to roam free in exchange for testimony ( my interpretation) during which time he fathered yet another meth affected infant ( fact). This was the choice made by Jeff Reisig.