By Crescenzo Vellucci

Vanguard Capitol Bureau

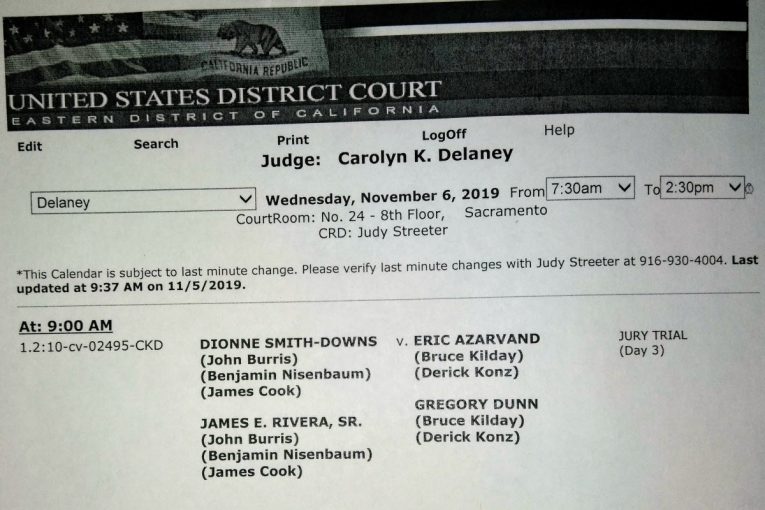

SACRAMENTO – Day Three in a U.S. District Court civil trial here Wednesday of Stockton city police officers who participated in the 2010 killing of 16-year-old special needs teen James Rivera, Jr., – driving a stolen van – had a little bit of everything.

The first part of the day saw city of Stockton lawyers continue to try to “dirty up” the plaintiffs in the lawsuit (Smith v. City of Stockton, et al) by suggesting Dionne Smith-Downs and James Rivera, Sr., were not good parents and therefore not worthy of winning the case.

The second half of Wednesday involved the testimony of Stockton city police officers, which supported more of the plaintiff’s charges than that of the city of Stockton defense.

But the majority of the afternoon heard the testimony of a retired Los Angles Deputy Sheriff, and longtime police procedures expert Roger Alma Clark, who provided bombshell testimony that the shooting should never have happened.

Clark said he analyzed the reports and facts surrounding the case and police response – specifically that of co-defendants Stockton Police officer Eric Azarvand and former Stockton officer Greg Dunn, who killed Rivera in a hail of bullets on July 22, 2010, as he sat in the driver’s seat of a stolen van in a darkened triplex garage.

Clark – a lieutenant in the LA Sheriff’s Dept., former station commander and police instructor whose broad and lengthy experience in law enforcement took about 10 minutes to recite – was not at all  complimentary of the officers’ procedures, especially that of Dunn, who was terminated by SPD and now operates a sand-blasting company.

complimentary of the officers’ procedures, especially that of Dunn, who was terminated by SPD and now operates a sand-blasting company.

Dunn’s face and neck became redder and redder as Clark’s testimony methodically criticized what Dunn did wrong in the shooting death of Rivera Jr. nearly a decade ago.

“They reached conclusions I disagreed with,” Clark said about the official reports and investigations that cleared Dunn and Azarvand of any wrongdoing.

Specifically, Clark took issue with the pair’s use of lethal force, and the firing of 29 shots by three officers, including the defendants. He called it a “tactical failure.”

Clark said law enforcement officers are trained to consider, first, alternative actions, and not react to “subjective fear,” as opposed to real or “objective” fear.

“I can imagine a lot of things, including fear. But fear needs to be reasonable and objective,” Clark said, noting that officers should have used “reasonable alternatives before using force, especially lethal force.

Dunn, specifically, said when he was on the stand Tuesday that it was his “fear” of being run over by the van or being shot that led him to emptying his handgun into the van driven by Rivera Jr. just seconds after Rivera didn’t respond to commands.

“The shooting should not have occurred. There were alternatives,” insisted Clark, explaining that the “van was contained, the suspect was contained” and Rivera should have had a chance to “surrender.”

He said that officers are trained, until it’s “muscle memory,” to not break from safety into the danger zone – something that Dunn appeared to have done by getting out of his patrol car, a “position of safety,” and standing right behind the van, which had been wedged into the garage after Dunn rammed it.

Clark described the steps necessary in a “high risk encounter,” including finding cover, containment, communication with the suspect, acknowledgement by the suspect and then instruction and apprehension.

Dunn had said he opened fire on Rivera because he didn’t respond to commands immediately. Clark said that was a mistake and that not responding to commands was not a reason to use force or lethal force.

In fact, Clark said Dunn and other officers should have moved, even if it meant backing up and using “tactical repositioning” so that it would have given the suspect a chance to respond.

There didn’t have to be injuries because “time” was on the side of law enforcement, Clark said, noting the suspect was contained and couldn’t go anywhere, even if Rivera had a weapon – which he did not – or if the van was moving backwards, and that’s been in dispute throughout the trial.

The defense team tried to counter that Clark didn’t have the experience to support his contentions, but Clark countered that he had, over the last five years, produced about 200 reports of officer involved lethal force. He’s been a consultant in police practices for years. He retired from LA County Sheriff’s Dept. in 1993.

Clark said he was generally “agnostic” in cases and said again that Dunn and others should not have used lethal force, and that even fears expressed by Dunn that he could have been hurt did not “justify shooting.”

“You just can’t shoot blindly. Officers are trained to get into position so they can see (the threat),” said Clark, suggesting that the reason Rivera didn’t immediately respond was that he could have been injured from the crash

Earlier, Smith-Downs, the mother of Rivera Jr., spent part of another day on the stand. Defense lawyers for the officer suggested that she didn’t take care of her son and was not involved in his life.

Smith-Downs countered that “I take care of all my kids.” She related how she went to the special needs school, and other programs to help with her son, made sure he visited his father, James Rivera, Sr., in prison and even handed over custody of the younger Rivera to her brother for awhile to get the teen out of a bad neighborhood in north Stockton.

“I did my best. I loved my son. I never gave up on him. I did all I could do, and I still don’t have my son,” Smith-Downs said, quietly sobbing on the stand.

Smith-Downs told the jury Tuesday that her son was diagnosed with “mild mental retardation” at an early age, and that she guided him through a special program and schools for years, before he began to “get into trouble” when he was about 14 because he started running around with the “wrong crowd.”

Rivera escaped from juvenile hall with another teen earlier in 2010 – his birthday was the day after he was killed, and his mother said the teen was excited, asking her to “do it big” and insisting she order a “special cake.”

But the next day, Smith-Downs was asleep when she received a phone call from a neighbor. She drove over to where officers had shot her son – Smith-Downs called it a “murder,” but the court told the jurors Tuesday to disregard it.

The senior Rivera was next. Defense lawyers asked how he could be supportive of his son while in jail – Rivera explained that he wrote and called his son frequently, saw him on visits and sent toys and other gifts, including money for his son that he earned doing odd jobs in the prison, where he was a cook.

Rivera said he did not know about his son’s problems, including being sent to juvenile hall, but blamed it on himself because he had stopped communicating with Smith-Downs. He didn’t even know his son had a disability.

“I just asked him if he was trying his best, and told him that was all I could ask for,” said Rivera. “If I would have known about his problems I would have said for him to ‘not go down that path.’”

Later, Stockton Police Sgt Sophal Nhem testified he was the one who had helped put out a spike strip that punctured at least one of the tires on the stolen van – he later pulled Rivera out of the van after the shooting, describing he heard a “gurgling” sound as he pulled the unconscious but alive teen out for paramedics.

Nhem also said he believed the van had not moved from before the shooting, to after the gunfire, something Dunn and Azarvand said did happen, and why they started shooting at the unarmed Rivera.

Former SPD officer Anthony Desimone then testified he inspected the scene, and confirmed that a spike was embedded in one rear tire which was flat and inoperable. He said the other tire was not flat but had dug a three-inch hole because the van was stuck and unable to move.

Desimone also said he pulled bullets or fragments out of the garage wall, and that fragments had gone through the wall into the adjacent triplex unit – although no one was injured.

At the end of the day, Judge Carolyn Delaney denied motions by the Stockton defense team asking to dismiss charges against the officers and the city, explaining there was ample evidence to let the jury decide.

The trial began Monday and is expected to last until Friday when closing statements are expected.