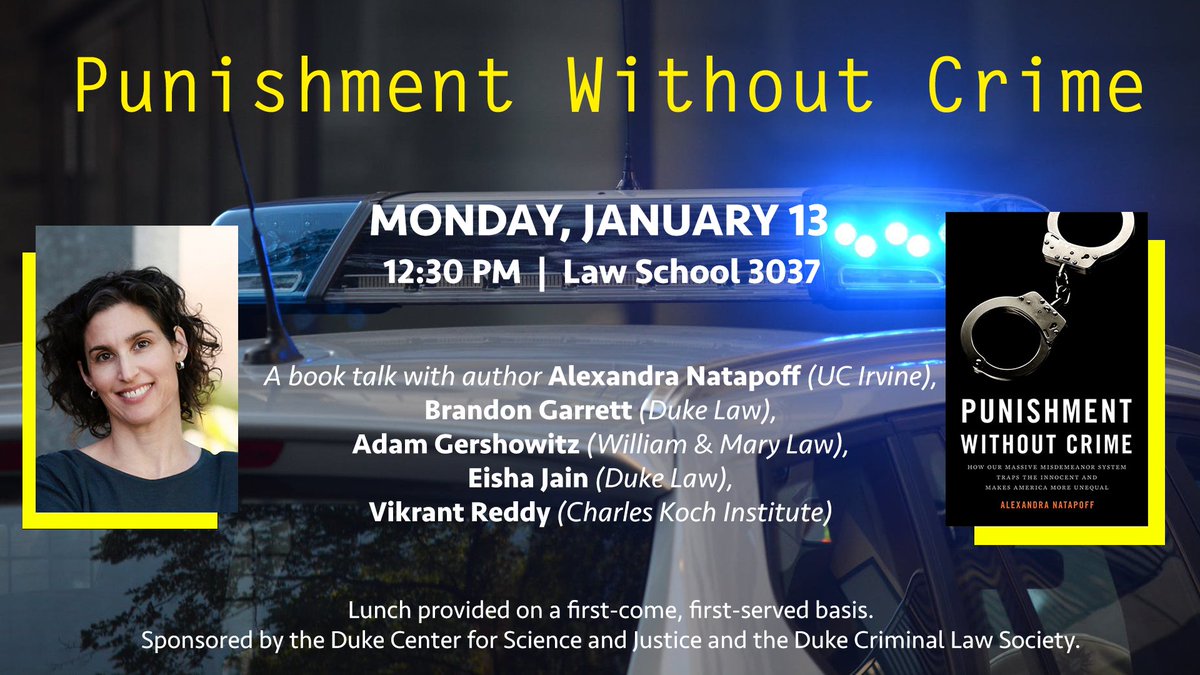

A Duke University Book Panel Featuring Author Alexandra Natapoff

By Danielle Silva

Duke University hosted a panel on Alexandra Natapoff’s Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal. The panel discussed their viewpoints of the book and followed with a short question and answer.

The panel started with Professor Adam Gershowitz, Professor at William & Mary Law School.

“The misdemeanor system is seriously messed up and this book is an exceptional tour for why it’s messed up… and what it is we don’t know about the criminal justice system,” he said as an introduction to the book.

Gershowitz noted that the book points out what we don’t know but should know, such as the number of misdemeanor offenses in the United States. When people ask questions about why they don’t know, he states that responses could range from dismissives like “I don’t know the answer to your question” or “No one can respond to that,” to interrogatives like “Why are you asking that?” or “Why do you need to know that?”

Gershowitz stated that responses such as these should be challenged.

He noted the criminal justice system holds many problems, including verbally or physically abusive responses to requests, policies of favoritism, the underfunding and understaffing of certain departments, and the pushing of guilty pleas.

In his case, Gershowitz wrote an article on trying to keep individuals from being placed in the criminal justice system. Harris County, he mentioned, has a process where police must have an intake prosecutor review the situation before an individual can be arrested.

This helps individuals from being put into the system, forcing them to face all the procedural difficulties all the way through.

Visiting Professor at Duke Law Eisha Jan spoke next, sharing that the book is valuable, as it shined a light on a system that is never talked about – especially in terms of what is thought about criminal law and the standard first-year criminal law course.

She noted that first-year criminal law courses focus on murder but don’t spend any time on misdemeanors – which is the bulk of criminal law. Jan also addressed how punishments are defined in a formal sense as a criminal sentence, but there are aspects that exist beyond that formal definition.

One such example included how low-level misdemeanor convictions can bar you from certain things, such as eligibility to live in public housing or receive student loans, and could result in immigration  consequences – all of which are not considered punishments.

consequences – all of which are not considered punishments.

Jan notes that hassle and degradation is part of the misdemeanor process. During her time as a civil rights lawyer, she represented a defendant who maintained his innocence and eventually had the case dismissed but still had to have multiple court appearances. She stated the system is made to “produce convictions,” where taking a quick plea is a less harmful alternative.

Some may view that misdemeanors are an alternative to more formal criminal punishment, but she stated they actually “contribute to net-widening by putting people into a system by criminalizing low-level activity that shouldn’t be criminalized in the first place.”

Senior Research Fellow at the Charles Koch Institute Vikrant Reddy commented on how he agrees with many parts of the book but would like to offer some comments about why people would disagree with it.

He noted that sometimes the government tries to get involved in problems such as punishing people for certain crimes, but that can lead to the situation becoming worse. In terms of what the book addresses, the misdemeanor system is out of control.

Reddy shared that he may be able to disagree because he can afford to, as he lives in a poster-child neighborhood where petty crimes do happen on a less notable scale.

Other neighborhoods may have petty crimes happen more often, which could be affecting the community – such as excessive littering or loitering.

Reddy referenced a talk he had with a late professor who had done survey work. The professor stated communities that have high crime care about public order and quality-of-life type issues. They view what they’re upset about as a fundamental criminal justice problem.

Reddy stated they may be overthinking it, or he may be underestimating the impact.

He noted broken window policing, which can wreck the trust between police and local communities but some evidence shows that people are less likely to commit crimes as a result. Reddy said there may also be other consequences they have to consider as a result.

In 2015, there was a legislative bill to make a small amount of jail time possible for people who littered. The author had been a black legislator from a black neighborhood who said littering was getting out of control in his community. Reddy had argued against the bill, stating that they were in a time where they were trying to decrease the number of black men in prison and this was going in the wrong direction.

The bill did not pass but Reddy considered whether the community had also wanted to address the littering with the same process. In terms of dealing with quality-of-life crimes, he quoted the book, stating, “Quality of life for who?” He asked how we can incorporate their concerns into criminal justice reforms.

Alexandra Natapoff, the author of the book, began her speech by noting how the criminal justice system is about misdemeanors. Eighty percent of criminal law consists of misdemeanors, with 20 percnet being felonies, or 3 to 4 million felonies in state courts, and 1-2 percent being murder and rape trials.

Natapoff pointed out that studies focusing on serious crimes make the criminal justice system seem unrealistic and misleading.

“Murder is not a good model for figuring out [the criminal justice system] – we don’t worry about whether or not we should treat conduct criminally when we deal with murders in the case of homicides,” she said.

Natapoff shared that individuals need to understand the scope of governance – “what kind of democracy do we want to have and what kind of role do we think our criminal system as it actually is, is not as we imagined it to be.”

The book points out empirical data but she lists the misdemeanor system’s role having three major issues: innocence, money, and race.

She noted that the innocence movement is “the most profound eye-opening reform trends” which tries to bring to light people who are convicted of serious crimes they didn’t commit. Natapoff notes how the movement never thinks about the hundreds and thousands of innocent misdemeanor convictions.

“Because the process is sloppy because we don’t check back, because no one’s paying attention, because we don’t check facts, and because people are under an inordinate amount of pressure to plead guilty in order to get out of jail to get back to their lives, to their children, to their work and they plead guilty to low-level offenses,” Natapoff explained.

In terms of the money, Natapoff noted how the criminal justice system relies on the fines and fees from misdemeanors.

“The criminal justice system is secretly taxing criminal defendants in order to run its own operation; we can’t understand this enormous world of misdemeanors without understanding how it is a way of criminalizing poverty and also a covert form of taxation that permits the criminal system to run itself,” she stated.

The racial role played a big part in the issue of mass incarceration today. She noted how misdemeanors have the largest disparities, affirmatively marking people of color as criminals, working to get them that first record.

“Race is an extricable part of the meaning of our criminal system and yet misdemeanors are the first step in the racialization of crime before anyone goes to prison,” Natapoff said.

Natapoff argued that individuals should start paying more attention to data collection, especially for misdemeanors and low-level dockets. She shared she was working with a legislator to pass a bill that has district attorney officers collect more data on low-level dockets.

Returning to her talk on governance, she asked how the criminal justice system is supposed to work and if it is supposed to be the right governance tool for certain situations. She also asked how we defined public safety, especially looking at the range of crimes from jaywalking to homicide and everything in between.

The first question during the question and answer portion addressed encouraging data collection.

Natapoff explained that Measures for Justice, a non-profit data collection organization founded by Amy Bach, was a free national database that had just criminal data state by state, and county by county. She noted how that made the landscape look different but also brought to light how much is “under-documented, under-theorized, and under-litigated.”

Another individual asked what to do about such a big problem.

Natapoff answered that her book’s last chapter titled “Change” talks about looking at the criminal justice system as an opportunity for a different system altogether, noting the laws themselves need to be altered. She notes that we need to think differently about misdemeanors and abolish the terms minor and petty from that dictionary.

Gershowitz also added that there is an incentive structure for law enforcement to arrest more individuals, but policy positions could be in place to prevent these cases from being in there in the first place. He noted even when cases are dismissed, problems still exist.

One person asked how to deal with legislature potentially seeing misdemeanors as a way to solve these issues.

“One of the governance tools that we deal with complicated messy social and economic issues – is not just an academic trick. We’re doing all this work through misdemeanors,” Natapoff answered. She asked if this work should be done through the criminal justice system or should it be through the welfare system, noting how money has shifted from the welfare system to the criminal justice system instead.

“We decide something is a crime – no more complicated than any other large social welfare problem that we have dealt with for decades,” Natapoff said.

Reddy stated that many tend to be consumed with national problem solving when ultimately the solutions would be local, with communities deciding to consider alternatives to the criminal justice system.

The last question of the panel concerned the future of change, especially considering how there is a consensus about how serious some issues are but also a massive difference in opinions.

Jan, for instance, noted that labels can obscure more than they illuminate. She stated we should start with the process of what’s under the massive umbrella of misdemeanors and consider what conduct should be punished and what shouldn’t.

Natapoff shared she believes that the future is bright because the conversations and awareness of the criminal justice system that is happening now is complicated, but we wouldn’t have had them years ago. She also stated we don’t need a perfect agreement, just enough agreement.

Reddy noted that there are other conversations about issues that we did not have in the past, such as issues of homelessness. He stated we should try to find longer-term solutions than what we did in the past and we have to be careful about moving forward.

Gershowitz noted that opinions on some crimes have changed over time, especially how we deal with them, but there is some consensus on how some of those things are addressed.