By Gabriela Tsudik

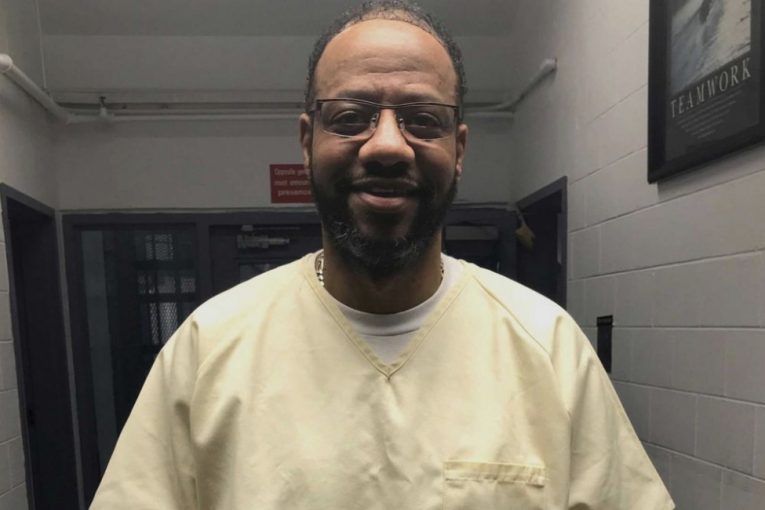

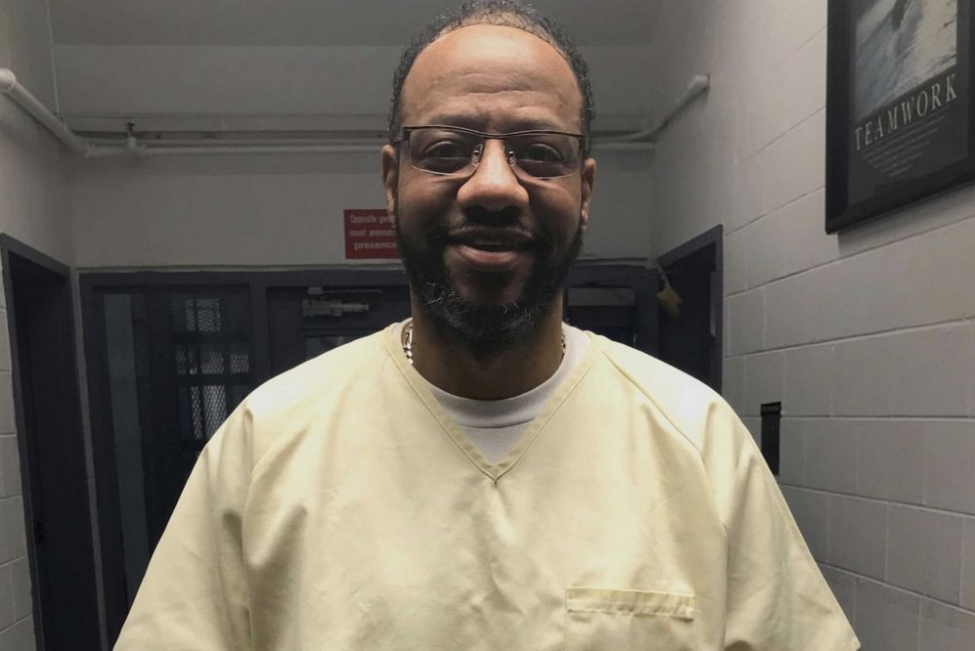

TENNESSEE – About four months from now, on Dec. 3, 2020, Pervis Payne, 53, is scheduled to be executed in Tennessee, after spending 32 years on death row.

Payne is an African-American who grew up in Tipton County, Tennessee, and both of his parents experienced first-hand life in the South under Jim Crow

On June 27, 1987, 20-year-old Payne was found at the scene of a crime: murder and attempted rape. The victims were a neighbor of his girlfriend and the neighbor’s 2-year-old daughter.

In court, Payne described what he saw as: “The worst thing I ever saw in my life.” Earlier that same day, Payne testified that he was waiting for his girlfriend at her apartment in Millington, Tennessee, when he saw a man covered in blood run out of the building. The man ran past him and dropped change and some papers while sprinting away.

Payne picked up some of these items before entering the building. He then noticed that the door to the apartment across from his girlfriend was open and he heard a noise. Upon entering, he encountered the victim, who had been stabbed 41 times and still had a knife stuck in her throat.

Payne tried to help. He also checked on the victim’s two young children, one of whom was still alive. He then immediately ran for help, just as police officers arrived at the apartment building.

In his testimony, Payne explained: “…I’m coming out of here with blood on me and everything. It’s going to look like I’ve done this crime.” However, is being at the wrong place at the wrong time a basis for the death penalty?

Furthermore, it is important to note that Payne has an intellectual disability, confirmed through testing. Thus, regardless of whether his conviction was wrongful, under the 8th Amendment it should be unconstitutional to execute him even if he were guilty. This amendment prohibits imposing harsh penalties and sentencing on mentally disabled defendants.

However, after certiorari was granted and the case moved to the Supreme Court, one of the key opinions was the principle of the punishment fitting the crime in question (the court established that the crime was a particularly aggravated and savage murder).

This case has had a lasting impact on victims’ rights. Legal scholars have cited Payne as a “capstone case” and as an example of symbolic violence—symbolic violence in the context of the oppression of women by men. This led to Chief Justice Rehnquist’s reliance on victim impact statements and the image of the perpetrator as a rabid animal with murderous and inhuman inclinations to justify the similar inhumanity of Payne’s death sentence.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge the role of racial biases in Payne’s conviction. For starters, innocent Black people are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than their white counterparts.

Studies have shown that the race of a victim can increase the likelihood of the accused being given the death penalty. For example, since 1976 almost 300 Black people accused of murdering white people have been executed, which is about 14 times more than the number of whites executed for murdering other whites, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Payne grew up hearing stories of white men torturing and murdering Black men in the area, and it is in the context of historical biases that the prosecution repeatedly referred to the victim’s “white skin,” when speaking of the wounds inflicted on her.

Though being in the wrong place at the wrong time led, in part, to Payne’s wrongful conviction, ultimately the prosecution’s case heavily relied on racist stereotypes of Black men to portray Payne as a violent and a hyper-sexual drug user.

Moreover, Payne did not know the victim and there was no evidence that the crime, if committed by him, was premeditated—yet police and the prosecution argued that Payne had made a move on her while under the influence of drugs and alcohol. When she rejected his advances, they say, he stabbed her to death.

However, there was no evidence that Payne used drugs, and the police never gave him a drug test, even though his mother begged them to perform one. Furthermore, there was also no evidence of drug use reported in the initial investigation.

But the prosecution continued with this narrative: a young Black man became violent as a result of uncontrollable sexual urges and drug use. Payne had no history of drug use or violence and had no prior criminal record. He had no contact with the legal system prior to June 27, 1987.

This reliance on harmful and fallacious stereotypes of Black men, instead of on the facts or evidence, not only influenced the prosecution’s case but also played a role in Payne’s unfair sentencing.

Payne was (wrongly) convicted in February 1988. But, today, there is some hope. In December 2019, Kelley Henry’s team at the Federal Public Defender’s Office in Nashville re-opened his case. They subsequently discovered previously hidden evidence: a bloodied comforter, sheets, and pillow.

Besides the (il)legality of hidden evidence, this led to a huge inconsistency because the prosecution had established that the crime occurred in the kitchen. This evidence also included significant DNA material that could prove Payne’s innocence, and the Innocence Project joined in filing a request for DNA testing in Payne’s case.

Notably, in 2006, well before this re-investigation, Payne’s request for biological evidence was denied.

Today, Payne’s fight for justice continues. He has maintained his innocence for more than 30 years.

Despite no prior criminal record and a mental disability, as well as a lack of sufficient evidence and inconsistencies, Payne is still scheduled to be executed in Tennessee in less than six months.

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9

The title of this article is:

But then the article states:

So the author claims Payne’s innocence but then throws ambiguity at that. So which is it?

I think the issue is with the headline, not the article.

So let me tell you how and why we ended up with the headline. The author writes the article, submits it to our editor who then edits it and sends it to me. I looked at the title and my first instinct was to modify it with “Likely” – I think I changed two or three other headlines today. But after reading it, I decided to leave it as written I think he’s probably innocent. Cathy, who does the post-publication editing, flagged it too but arrived at the same conclusion. You want to quibble fine, but it’s a headline not a legal authority.

“probably innocent” or “possibly innocent”. Either way you have no way of knowing for sure at this point.

I have no way to know for sure that I’m not trapped in someone’s dream. But I think if you count up the true evidence in this case, you arrive at a reasonable conclusion of innocence and really for a headline, that’s all you need. But of course we can go back and forth and argue this minor point for 50 posts.

That was a great comeback! Though I too have issue with the headline, I’m dropping it. I’m adding that snappy, sarcastic comeback to Alan Miller’s quiver of snappy comebacks, and that is more than worth the price of admission to the article.

The Green Mile?

Surely he should not be executed prior to DNA evidence, at the very least. Also problematic is the withholding of evidence. Can we at least not agree on that?