By Roxanna Jarvis and Cailin Garcia

CALIFORNIA – After decades of fighting for his release, Douglas Ray Stankewitz may finally have a real chance at freedom.

In an all-encompassing Writ of Habeas Corpus filed by his legal team, including J. Tony Serra and Curtis Briggs, new discoveries show that evidence in his case was greatly mishandled by detectives and sheriff deputies in Fresno—Stankewitz may have been framed for the murder of 22-year-old Theresa Graybeal in 1978.

Stankewitz, a California Native American who prefers to be called “Chief,” is the longest-serving condemned inmate at San Quentin State Prison with a total of 42 years.

Just last year, he had his sentence reduced from death to life without parole, but Stankewitz also stands as the longest-serving death row inmate in California. He was convicted for the murder of Theresa Graybeal and sentenced to death at the young age of 19.

The Initial Arrest

On the night of February 8, 1978, Stankewitz was accused of kidnapping, robbing, and then murdering Graybeal. Four other individuals, Marlin Lewis, Christina Menchaca, Tina Topping, and Billy  Brown, were also involved in the incident.

Brown, were also involved in the incident.

The story on record states that it all began that night when the four became stranded in Modesto. Hoping to hitch a ride by stealing a car, they set their sights on Graybeal outside a K-Mart store, forced her into her vehicle, and drove off.

After buying and shooting up heroin in Fresno, the group drove to Vine Avenue and 10th street in Calwa. According to Brown’s testimony in court, it was in Calwa where he witnessed Stankewitz raise a gun and shoot Graybeal on the back of her head. “Did I drop her or did I drop her?” Brown quoted Stankewitz as saying to the group.

Later that evening, Stankewitz, Menchaca, Topping (still driving Graybeal’s car), and Lewis were arrested by Fresno police. Brown was dropped home earlier and told his mother what had occurred.

On October 12, 1978, Stankewitz was sentenced to death for the murder of Graybeal. In August 1982, Stankewitz’s case was automatically appealed, and remanded to Superior Court, due to the trial court’s failure to hold a competency hearing. But Stankewitz was once again convicted and sentenced to death in November 1983.

A Wrongful Conviction

Despite being found guilty, Chief has claimed his innocence since day one. To him, it’s all in the evidence.

In 2017, new evidence was discovered which the prosecution had concealed in previous trials. Such evidence raised the possibility that a wrongful conviction had occurred.

Despite pleas for organizations like the CA Innocence Project to take on Chief’s case, there was no such luck. The Innocence Project does not disclose their reasons for not taking a case. It’s been surmised that what stopped The Innocence Project from taking on Stankewitz’s case was the disarray of files and documents, as well as the lack of distinctive DNA evidence to prove Chief’s innocence.

That’s when Alexandra Cock decided to step in. Cock, involved with Native American communities, has worked with several tribes on social justice issues. She was introduced to Stankewitz through a mutual friend in 2014.

Since then, she has been working tirelessly as a paralegal in the case. She has reviewed all documents involving the case and is responsible for the collection and organization of evidence used in the Writ of Habeas Corpus.

Before the pandemic, Cock made regular visits to Stankewitz at San Quentin State Prison, seeing him weekly for almost three years. Today, the two communicate through letters that  Stankewitz writes on his typewriter.

Stankewitz writes on his typewriter.

To assemble the Habeas, Cock reviewed 52 bankers boxes of documents from Stankewitz’s past lawyers and trials. She read and recorded all the evidence and also assisted in writing the motions for his release.

“[The boxes were] about the size of those cases that hold paper,” Cock told Vanguard Reporters. The discovery documents from the prosecution alone came out to be approximately 4,000 pages long.

But what was found within those papers turned out to be shocking and well-worth the 17-months of strenuous work.

Mishandled Evidence

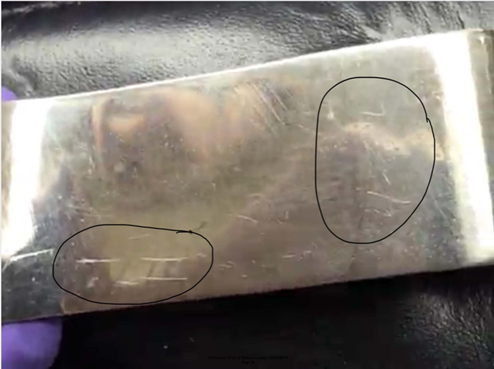

Among the documents, a gun trace report was discovered showing that the gun allegedly used in the crime had been in sheriff custody five years prior to the murder. The crime occurred in 1978, yet the trace report (completed two days after the crime) showed it being in sheriff custody since June 1973.

Along with the gun came its holster with the initials “TL III” and the 1973 date engraved onto it. Those initials belonged to one of the lead detectives in the case, Thomas Lean III. “This had to have been in [sheriff] custody,” asserted Marshall Hammons, a legal intern assisting Cock with the writing and research for the case. “Whatever gun [the sheriff’s department] offered in evidence, had to have been in [sheriff] custody during that process.

Due to conflicting police and sheriff reports, the legal team is unsure how the gun became evidence. The vehicle, originally with the Fresno police and allegedly with the loaded murder weapon in it, was moved in the middle of the night unlocked and unsealed to the unlocked lot of the Sheriff’s Department.

At the time that the vehicle was initially in police custody, officers did not search or photograph the vehicle. It was only when the car was transferred over to sheriff custody that the gun was allegedly recovered under the passenger seat.

Roger Clark, an expert and former Los Angeles Sheriff helping with the case, looked over the trace report and confirmed its findings. In a declaration, Clark stated the evidence “indicates the possibility of a throwaway (a firearm held by police for the purpose of framing an innocent person for a shooting) which was planted to satisfy the case about Stankewitz.”

The gun was far from the only thing suspicious about the investigation.

During Stankewitz’s trials in 1978 and 1983, prosecutors claimed the same gun was used in two separate cases, the Graybeal murder and the robbery of a man named Jesus Meras.

It was alleged that a .25 caliber was used in both instances. Although containing .25 caliber casings, when the defense inspected the evidence folder from the Meras case in 2017, it was labeled by the Sheriff’s Department as containing .22 caliber shell casings. This evidence was confirmed in a report by a DA investigator.

In the original report by a Fresno Sheriff about the Meras scene, it was stated that three .22 caliber casings were collected at the crime scene. It is also stated that photos were taken of the .22 casings. The .22 shell casings and photos have never been produced to the defense.

Curtis Briggs, one of the lawyers representing Stankewitz, claims the .22 bullets from the Meras case were switched out with three of the .25 caliber shell casings from the Graybeal case gun, test-fired on February 11, 1978.

“[It was] an apparently successful attempt to deceive the jury, judge and Defense into believing that the physical evidence supported the notion that the same weapon was used in both crimes,” wrote Briggs in a January 2019 motion.

Prosecution and law enforcement reports state that both crimes happened on the same day. But in a March 2020 interview, Meras recalled the robbery occurring in either 1975 or 1976, not 1978.

Also, the jacket of one of the co-defendants, Marlin Lewis, was taken out of evidence by one of the detectives, Allen Boudreau, and never returned. In a normal procedure, a report must be written to explain the purpose of why evidence is being taken. The evidence must also be recorded when returned and inspected by a “property custodian” to ensure that it is still in its original condition. None of this ever occurred.

In Clark’s statement, he wrote that the actions of Boudreau indicate a “specific intent to remove evidence.” Clark wrote, “Based on the extensive misconduct that occurred in this case, Detective Boudreau probably took Marlin Lewis’ jacket because he saw the victim’s blood on it and realized that it was exculpatory for Stankewitz.”

The defense team believes Lewis was responsible for shooting Graybeal. “We don’t know for sure, but we believe he was the shooter. He was wearing a blue jacket…[it was] very distinctive because it had a patch on the arm that said Red Power, with a picture of an Indian,” explained Cock.

The jacket Lewis wore is only one of the many pieces of evidence missing in Stankewitz’s case.

In the Habeas, a table is provided listing all that has disappeared from the investigation, including the bullet which killed Graybeal, interview tapes from all co-defendants the day after the murder took place, and arguably one of the most important items: prosecutors’ notes during the preparation of Billy Brown for his trial testimony.

Billy Brown’s testimonies held great weight during both of Stankewitz’s trials. Although his testimony contradicted the facts of the case, they were arguably what prosecutors used to pin Stankewitz for Theresa Graybeal’s murder.

As the only co-defendant put on the stand to testify, in both 1978 and 1983, a 14-year-old (and then 20 year old) Brown claimed he witnessed Stankewitz shoot Graybeal in the back of her head.

Yet, the evidence shows that Graybeal was shot on the side of the head. The bullet also struck at an upwards angle of 10 degrees, meaning the shooter had to have been shorter or close to the same height as Graybeal, 5’2.5”. Stankewitz is a tall man, standing at 6’1”. “There’s a big difference, there’s a big difference,” said Alexandra Cock. Lewis, who was 5’3”, fit closer to who could have shot her.

In 1993, Brown recanted his statement and claimed that he was forced to testify falsely by DDAs James Ardaiz and Warren Robinson at both trials. “I was pressured up the a**,” Brown stated. “If I did not say what they wanted, they would threaten me with homicide charges.”

Brown recollected being taken out of juvenile hall by either Ardaiz or one of the other detectives to go over his testimony. He would go to Ardaiz’s office on the weekends to practice it. Although a minor, Brown’s interviews were not supervised. This would have made it easy for Ardaiz and Robinson to coerce Brown into telling their false narrative.

If this had indeed occurred, notes written by Ardaiz and Robinson in both the first and second trials would have contained carefully written down statements of what they wanted Brown to say in court.

At one point, Brown recalled what happened when he began to tell the truth during the second trial. “The district attorney (Robinson) pulled me off the stand and told me ‘no this is the way it happened.’ I went back and testified to that fact.”

If the notes had ever been shown, Brown would have been taken off as a witness. “Of course, because the DA claims that the files are gone for good, Mr. Stankewitz is forever prejudiced by the loss of files,” argued Briggs in his 2019 motion.

In the same 1993 recantation, Brown said that he never saw Stankewitz with a gun, noting “I did not at any time see Doug Stankewitz holding a gun. I did not see who pulled the trigger…I never heard Doug say anything about ‘dropping her’. It was Lewis who said that.”

Brown was granted immunity for his testimonies. Out of all those questioned about the incident, Stankewitz was the only one who didn’t confess to being involved in Graybeal’s murder.

“Chief has been right about everything he’s told me,” Briggs stated. If Stankewitz is truly innocent, why was he framed? While there isn’t a definitive answer, the legal team believes it was due to his family’s relationship with the Sheriff’s department.

“They had a reputation in the community… Eleven children by five different moms and several of them had gone to prison,” said Detective Lean in a March 2020 interview after being asked if he knew the Stankewitz family.

Stankewitz’s Childhood and Upbringing

Even before his conviction, Stankewitz’s life was not easy. Stankewitz had a troubled childhood, growing up in an impoverished family that constantly cycled through the criminal justice system.

His father was a known member of the Hell’s Angels and his mother was convicted of manslaughter. Stankewitz’s older brother, Johnnie, was also involved in a violent shoot-out which injured an officer when Stankewitz was just 13 years old. Even today, all of Stankewitz’s remaining siblings are currently incarcerated.

Stankewitz had a poor relationship with his mother, who emotionally and physically abused him from a young age. She was known to struggle with alcoholism and drank while she was pregnant with him. Stankewitz was exposed to drugs by his brothers at the age of five.

When he was around six years old, Stankewitz was involved in an incident where he accidentally dropped his baby brother. In response, his mother beat him with an iron cord so terribly that ended up hospitalized for a week. Understandably, Stankewitz was removed from her custody after that.

Stankewitz was then taken to Napa State Hospital, where he stayed for nine months. Not much is known about the time he spent hospitalized, but it is documented that he was given heavy-duty drugs like Thorazine (used to treat schizophrenia) that may have influenced his current mental state.

“Because most of the records have been lost and the treating physicians have died, we don’t even really know what all happened there,” said Cock.

After his time at Napa State Hospital, Stankewitz was placed into foster care in Sebastopol, California. He describes the time spent with his foster family as “some of the best years of his life.”

Stankewitz recalls the fond memories of riding his bike to school every day with his puppy Lulu and playing with the animals next door which belonged to his circus-performing neighbors. In Sebastopol, Stankewitz attended church and would go to all the potlucks.

After three years, he was unfortunately removed from his foster home and sent back to his mother for unknown reasons. He lived with her for a while and even moved in with his aunt for some time.

In the end, his family reported him to local authorities for being “out of control” and he was sent to juvenile detention. As a teenager, Stankewitz spent time in group homes before he was arrested for Graybeal’s murder at 19.

for Graybeal’s murder at 19.

Systemic Failures of the Criminal Justice System

Given all of the circumstances in Stankewitz’s case, how could he have been sentenced to death twice, and why is he still in San Quentin?

“No one looked at the evidence,” says Stankewitz – and he is correct.

In the guilt phase of Stankewitz’s first trial, the appointed public defender presented a diminished capacity defense, arguing only that Stankewitz was too high on heroin at the time. In his second trial (1983), attorney Hugh Goodwin attempted to discredit Billy Brown but failed to take the steps necessary for a good defense.

In a declaration by Goodwin in 1995, Goodwin stated that he did not consult with or collect files from any of Stankewitz’s prior attorneys (both trial and appellate); He did not interview or collect files about Stankewitz’s family members, foster parents, or teachers to learn about his background.

Most importantly, Goodwin did not interview or investigate Billy Brown – the person he was attempting to discredit. In all, the declaration lists 20 things Goodwin failed to do as Stankewitz’s appointed attorney.

“They had an ethical duty to go look at the evidence. A cursory review of the evidence would have shown this just doesn’t line up,” argued Briggs when speaking about the failures of Stankewitz’s previous attorneys. “They didn’t just not do a good job from a stylistic point [of view], they failed a statutory requirement in death cases [specifically].”

Since his second death sentence, Stankewitz has fought for his release. But the road to freedom has not been easy.

When in Fresno Superior Court from 2017-2019, the legal team states that the judge assigned to Stankewitz’s case, Honorable Arlan Harrell, was unfair.

“He stated on the record that he would make sure this man gets a fair trial, but then denied multiple defense motions, some without giving us the opportunity to make an argument. He failed to rule on at least one important motion and ruled against us without a reasonable basis for doing so,” the legal team said.

This included motions to dismiss showing prosecutorial misconduct and motions for a new trial upon the discovery of evidence covered up by the prosecution.

On April 19, 2019, the DA filed to have Stankewitz’s death penalty dropped, claiming that they did not know about the mitigating factors of Stankewitz’s background. According to Cock, the prosecution records show that they had extensive records regarding mitigation. “They knew about that at the time of his second trial and at the time of his first trial,” Cock explained.

As of today, Stankewitz has attorneys who Cock and Hammons believe can give him the freedom he deserves.

Cock spent one year searching for lawyers to take the case pro-bono. Then, she finally got lawyers Curtis Briggs and J. Tony Serra to agree to represent him.

Both Briggs and Serra are big names in the Bay Area, known for representing defendants in the “Ghost Ship” warehouse fire in Oakland, as well as Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow, a former leader of one of San Francisco’s Chinatown fraternal organizations. Serra has dedicated his decades long legal career to defending the underserved, pro bono, winning many, many acquittals.

Elizabeth Campbell is also involved in the case, standing as Stankewitz’s sentencing appeal attorney.

In a written brief by Campbell, she demonstrates through laws and statutes how Judge Harrell violated the constitution in denying appeals and motions made in court. It’s an understatement to say that Campbell has impressive legal credentials. She has briefed, argued and won a California criminal case before the U.S. Supreme Court. “She’s got the chops,” stated Cock.

Currently, Stankewitz’s attorneys are waiting for the court’s response to the Habeas.

The Habeas, if approved, could grant a retrial or dismissal of Stankewitz’s case. Interestingly, it was filed on Wrongful Conviction day this year. “Woot! I’m like is that the perfect day to file it or what?” exclaimed Cock with a smile.

Who is Stankewitz Today?

Despite spending nearly his entire life in prison, the people who know Stankewitz praise him for his positive attitude and kind demeanor.

“Chief’s extremely kind, he’s extremely warm, and he’s smart. He really does want to help and love people,” Hammons told Vanguard reporters.

Stankewitz finds little ways to brighten up his day even as an inmate at San Quentin.

“One thing about him now, which I believe has been true about him his whole life, is he loves food,” Cock said with a chuckle. Stankewitz enjoys cooking for himself and uses spices to try to make the prison food more palatable. He also spends time writing letters to Cock and his attorneys using his typewriter.

Though his past attorneys have claimed that Stankewitz struggles with a mental disability, the legal team describes him as quite intelligent. Over the years, he never ceased in his search to unveil the evidence that could lead to his exoneration.

“He was keeping up with the legal concepts I was talking about and told me things that I had no idea about that I had to learn,” Hammons noted. “So, this isn’t someone that is mentally challenged.”

In a letter he wrote to Vanguard reporters, Stankewitz described the Habeas Corpus as his “voice” and “a clear picture of [his] wishes and desires.” He hopes that by sharing the information in the Habeas, he can raise awareness of his case and have the public hear his story.

“I honestly can say that I found it easy to continue to fight as hard as I have for over 42 years because of the mere fact that I knew and know that I am INNOCENT,” Stankewitz wrote in his letter. “Because of this fact, I knew that I could and would never give up nor stop fighting, fighting to not only prove that I am innocent but to always show and prove that I was FRAMED.

“One can never give up or stop fighting when one knows the truth and even though I have paid an unwarranted price of 42 plus years, I am grateful for my legal team that I now have as they have believed in me and gave my side of the story,” he continued.

“I truly hope that the contents of the [Habeas have] given you a profound picture and understanding of my feelings… and the unwarranted and unjust 42-year fight I have been subjected to for being innocent. I want to thank you for your time and concern in my case in hopes you will continue to share my voice as I only speak innocently,” he ended the letter, which he signed with his preferred name, “Chief Stankewitz.”

Vanguard investigative reporter Roxanna Jarvis is a fourth-year student at UC Berkeley, currently majoring in political science with a minor in public policy. She is

Vanguard investigative reporter Roxanna Jarvis is a fourth-year student at UC Berkeley, currently majoring in political science with a minor in public policy. She is  from Sacramento, CA. And her reporter partner, Cailin Garcia, is a senior at UCLA, majoring in sociology with a minor in professional writing. She is from Santa Clarita, CA

from Sacramento, CA. And her reporter partner, Cailin Garcia, is a senior at UCLA, majoring in sociology with a minor in professional writing. She is from Santa Clarita, CA

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9

Support our work – to become a sustaining at $5 – $10- $25 per month hit the link:

On what grounds was his death sentence overturned?

Curtis Briggs asked the DA to look at some of their evidence and based on that the court was petitioned to reduce the case to LWOP.

Yet, as the article says, he’s innocent… so LWOP is a very servere ‘injustance’… fish or cut bait… is he totally innocent of all crime, was he over-charged, and is LWOP just (particularly if he was over-charged)?

And, to pick up on Robert C’s comment, if the ‘chief’ was not the “trigger-man”, but participated, what would his sentence have been?

What was the adjudication of the others involved?

Somebody was guilty… unless it was a ‘suicide’… there is a victim… someone is culpable… article does not ackowledge someone died (fact), likely was murdered, and focuses only on they had the wrong person who did the deed…

Innocent? Perhaps of the magnitude of the crime charged… but, ‘accessories’ are not factually ‘innocent’, just guilty of a lesser crime… For “innocent” one would have to have been ‘not there’, or have tried to intervene unsuccessfully…

The article does not indicate that the subject was not guilty of ANY crime…

In the Habeas petition, his attorneys argue he was framed by police and the gun was planted.