By David M. Greenwald

By David M. Greenwald

Executive Editor

Woodland, CA – For those who want to argue that the political landscape has rapidly shifted on crime and punishment issues, Jeff Reisig has spent most of the last year-plus attempting to soften his image and position himself between the tough-on-crime plank where he has traditionally lived and the progressive prosecutors who have pushed for wholesale reform in the criminal legal system.

But despite the attempt to rebrand himself with a softer image, Reisig has largely stayed true to form and that came out last week when during a discussion on Prop. 47, he, among other things, likened Prop. 47 to decriminalizing possession of hard drugs—as though shifting from a felony to a misdemeanor for possession was the equivalent of getting a speeding ticket.

During his exchange with challenger Cynthia Rodriguez he said, “what happened is, in 2014, voters of California passed an initiative called Prop. 47. It changed the law. And what it did was decriminalize the possession of hard drugs—heroin,  methamphetamine, cocaine, fentanyl, ecstasy, whatever, from felonies to misdemeanors.”

methamphetamine, cocaine, fentanyl, ecstasy, whatever, from felonies to misdemeanors.”

Reisig explained, “Before Prop. 47 if someone was arrested with methamphetamine, for example, they would be arrested on a felony, taken to court and the first thing we try to do is get them into drug treatment. That’s a fact.”

He continued, “Well, when Prop. 47 changed it from felony to a misdemeanor what we’ve seen across California is a rapid drop-off in people wanting to participate in treatment at all. The reason is there’s no consequence. It’s a misdemeanor, it’s a ticket. It’s no different than walking down the street with an open beer.”

Reisig clearly favors the heavy stick approach to treatment—whereby a person facing a heavy punishment is compelled to go to treatment to get themselves clean. The problem with that approach is that most experts do not believe it works very well.

Last year for example Jeff Reisig worked with Assemblymember Kevin McCarty to support AB 1542—which would have created a pilot program that would offer a ‘secured residential treatment program’ for drug offenders suffering from substance use disorder (SUD) who have been convicted of drug-motivated crimes because of SUD.”

The bill would have authorized the court “to divert an offender to confinement in a secured residential treatment facility if it determines that the crime was caused in whole or in part by that individual’s substance abuse.”

While the Enterprise ran an editorial proclaiming, “Yolo County has an opportunity to be a leader in criminal-justice reform,” advocates were alarmed at the prospect.

Ultimately the governor vetoed the legislation after it was overwhelming approved by both houses of the state legislature.

“I have several concerns with this bill,” Yolo County Public Defender Tracie Olson told the Vanguard last year.

“Study after study show that coerced treatment does not work in the long run,” she said. “Compulsory treatment leads to twice as many opioid-related overdose deaths as compared to voluntary drug treatment. Instead of spending millions of dollars each year to expand local jail bed capacity, we should be investing in stable housing (the root of homelessness), employment, medication assisted treatment, and supported transition from voluntary drug treatment.”

For Drug Policy Alliance, a group that looks to reduce the role of criminalization in drug policy, this approach is a step in the wrong direction.

“Coerced treatment isn’t proven to be better than voluntary treatment, it doesn’t have better outcomes to threaten people with incarceration or force them into a locked facility,” said Glenn Backes, a social worker and Public Policy Researcher with Drug Policy Alliance.

He also noted that the cost of such a program is much higher than a comparable voluntary program, and he argues we have not invested in an adequate voluntary treatment.

“It is much more cost-effective to invest to create the treatment opportunities, housing opportunities in the community to get people off the streets and to reduce their drug use rather than to threaten to put someone in jail if they don’t do this,” he said. “To put someone in jail is not cost-effective and it’s not science-based.”

In July, DA Candidate Cynthia Rodriguez in a letter published in the Vanguard, wrote, “AB 1542 would force Yolo citizens with drug and alcohol dependencies into a coerced treatment program that is no different from, or more humane than, existing policies that harm a medically vulnerable population.”

From her view, “coerced, incarcerated ‘treatment’” is really no different from current “failed inhumane policy of criminalizaing substance abuse disorder that currently exists.”

She writes, “Best evidence from professionals in medicine and rehabilitation tells us that coerced programs are rarely followed by any increase in sobriety at all, and they will not alter the medical condition of a person who is coerced to attend this program as an ‘alternative’ to incarceration.”

The Human Rights Watch has also been a strong opponent.

In a letter to the Assembly, they wrote, “It runs directly counter to the principle of free and informed consent to mental health treatment, which is a cornerstone of the right to health. Conflating health treatment and jailing, as envisioned by AB 1542, risks substantial human rights abuse, is ineffective as a treatment, and takes resources and policy focus away from initiatives that are much more likely to help people.”

As it turned out, Governor Newsom shared those concerns.

“I understand the importance of developing programs that can divert individuals away from the criminal justice system, but coerced treatment for substance use disorder is not the answer,” Governor Newsom wrote.

He continued, “While this pilot would give a person the choice between incarceration and treatment, I am concerned that this is a false choice that effectively leads to forced treatment.”

He added, “I am especially concerned about the effects of such treatment, given that evidence has shown coerced treatment hinders participants’ long-term recovery from their substance use disorder.”

Had DA Jeff Reisig come together with these groups to create a viable alternative to incarceration for drug related offenses, he probably could have gotten the legislation passed. Instead, he attempted to go it alone and ignored repeated criticism from community-based groups.

His answers last week continue to show that he does not believe that alternatives to incarceration can work without the threat of incarceration—even though study after study actually shows the opposite, that people need to come to the decision voluntarily in order for it to stick.

People point out that prison sometimes is the shock people need to get clean—maybe in some instances, but the data say otherwise. Over three quarters of all state drug offenders released from state prison were rearrested within five years, according to a 2017 report from the US Sentencing Commission.

Moreover, a PEW Study found “no relationship between drug imprisonment rates and states’ drug problems.”

“One primary reason for sentencing an offender to prison is deterrence—conveying the message that losing one’s freedom is not worth whatever one gains from committing a crime,” PEW wrote. “The theory of deterrence would suggest, for instance, that states with higher rates of drug imprisonment would experience lower rates of drug use among their residents.

“If imprisonment were an effective deterrent to drug use and crime, then, all other things being equal, the extent to which a state sends drug offenders to prison should be correlated with certain drug-related problems in that state,” they wrote, but instead PEW found “no statistically significant relationship between drug imprisonment and these indicators. In other words, higher rates of drug imprisonment did not translate into lower rates of drug use, arrests, or overdose deaths.”

So the experts and the data are telling us that the stick approach and coerced treatment do not work.

One phrase you won’t hear from Reisig—harm reduction.

President Biden made news in some circles two weeks ago when he incorporated it, albeit briefly, into his State of the Union address.

He said, “Increase funding for prevention, treatment, harm reduction and recovery.”

It was a start.

“We’re grateful the Biden-Harris administration is prioritizing [harm reduction] and is the first administration to incorporate it into their overall overdose prevention strategy,” Grant Smith, deputy director of national affairs at Drug Policy Alliance, told Filter. “But that’s not to say they shouldn’t be doing a lot more. We certainly need a lot more funding.”

As Maya Schenwar and Victoria Law argue in Prison by Any Other Name, mandated treatment and other confinement-based addiction alternative ignore “the realities of substance use in society: most people are not debilitated by physical dependence on the substances they use, whether they be alcohol, caffeine or heroin.”

Moreover, “an involuntary and immediate cessation of use generally doesn’t lead to lasting recovery-especially when it comes along with surveillance and confinement.”

They cite a 2016 Boston University Medical Study that found “mandatory treatment isn’t effective in reducing drug use,” and, in fact, it ultimately “does more harm than benefit to the patient … by coercing them to participate in medical programs that they might not consent to otherwise.”

But, despite the setback last year, DA Reisig is still hitting the same note—even though the research is against his approach.

There’s no context to this article, in regard to the claim that mandatory sobriety (in regard to drug or alcohol use) “doesn’t work”. How large were those studies, for example? How often has it been attempted?

I would think that the “largest study” of all regarding this might be found in those released from prison, assuming that they did not have access to drugs while incarcerated. (For those who were addicted prior to incarceration.)

Those who seek voluntary treatment are more motivated in the first place, compared to those who don’t seek treatment. As such, one cannot compare the two, in terms of results.

Are there large numbers of drug and alcohol addicts seeking treatment, but are turned away due to lack of capacity in those programs? If not, then one might argue that voluntary treatment has an even worse track record than “forced” treatment (forced abstinence).

Society (at large) cares when those with mental health or substance abuse issues create problems for others.

One phrase you won’t hear from Alan Miller—harm reduction.

I laugh whenever I read that term, ‘evidence-based’, because it’s only used by justice reform progressives, and as a dog-whistle that it is ‘the evidence that supports our policies’. It feeds into the godhead Science, the trough from which the progressive wing feeds.

True as stated for ‘most people’ if you include caffeine especially. But an incredibly deceptive comment away from the realities of substance abuse for those who are not ‘most people’, but rather are addicts, and if you exclude caffeine which is debilitating to almost no one.

The strangest thing to me in this argument about voluntary vs. involuntary. There’s this missing link — the notion that someone who would be given treatment during time served anyway would instead seek voluntary treatment if they were not incarcerated. The whole reason voluntary is more successful is that people so volunteering have already made the decision to change, which is 90% of the battle. So, if you are pounding the evidence-based drum, how can one omit such a large piece of basic logic from the evidence?

Making a serious decision to change is a point few reach, and the scourge of addiction eats the mass of even those who make this choice. The problem at heart is that those addicted are the walking dead, they just haven’t died yet. Only a small fraction will find a way out, and no one can change that.

If this really is true, then fine — there should be facilities to meet the voluntary demand. But so much of this article comes across as justification for supporting the very lucrative recovery program industrial complex. And a weird kink of the reality is the more times someone gets treatment, the more money goes into this industry. Not saying they all model it this way and addiction lends itself to this, but be aware.

Addicts bring down society in the same way an addicts brings down a family. The human humane thing to do appears to be to support, to keep warm, to give money. All of which will be used to further the addiction. It is one of the hardest things for families to understand the best thing to do is cut them off to suffer the fate of their decisions — most especially because one of those fates is likely death. But support only extends a comfortable addiction and hastens death. And so it is with societal support programs of active addicts. No evidence (“based” #chuckle#) will convince me otherwise. I do not bow to the progressive godhead Science.

Am I saying “do harm” ? Yes I am. #pearlsclutched#. Addiction hurts the user and should hurt. That is the chance for a way out.

I do not agree with the notion that addiction and possession should in of themselves be prosecuted. What must hurt is the committing of crimes. And in my book that includes sleeping in public places while addicted, because it hurts our society and our cities and towns. We cannot continue to live like this, poop and litter and bike parts as part of life. Housing programs will never solve this.

I realize with the Boise Decision that ship has sailed. That won’t prevent me from heading out to sea with a speedboat, tracking down that ship, and convincing it to come back to shore.

Alan – according to NCDAS, there are around “31.9 million use illegal drugs. 8.1 million of 25.4% of illegal drug users have a drug disorder.” So that would bear out my point.

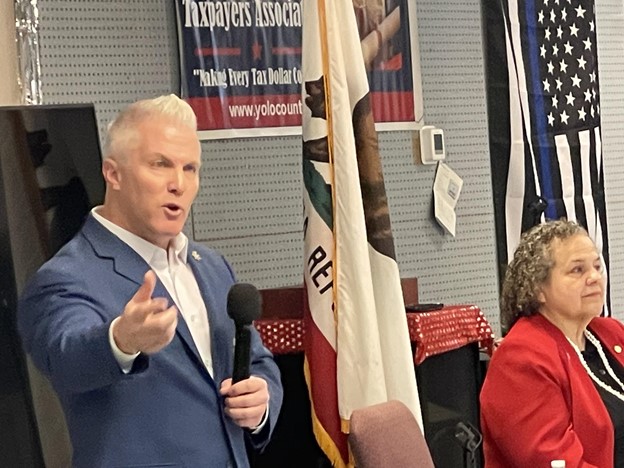

Looking at the photo of Reisig with his hand outstretched I commend the author for not claiming it was a white supremacy sign.